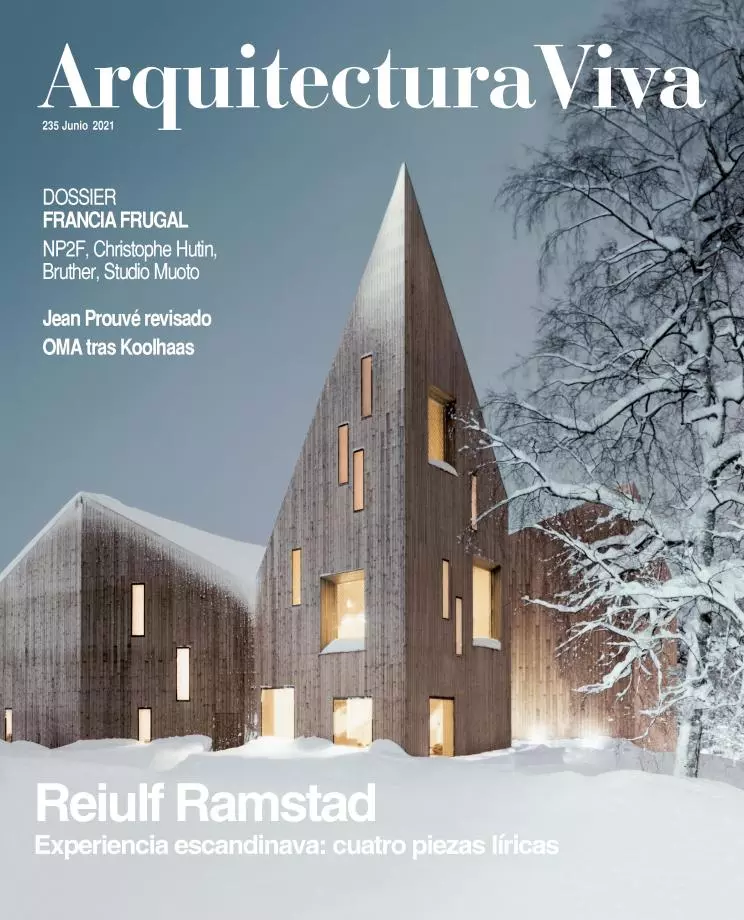

Pabellón de Alemania. Barcelona, 1929

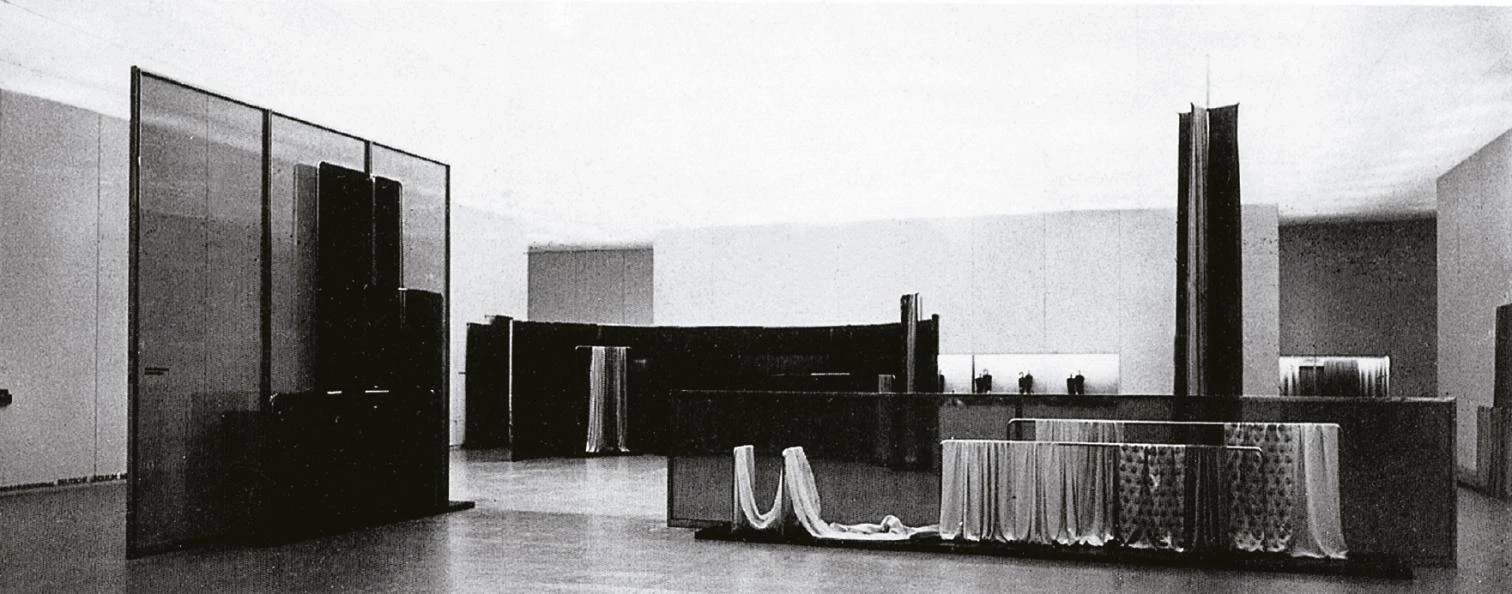

In the ephemeral Glasraum of the Werkbund’s 1927 exhibition in Stuttgart, the dynamic Wrightian space flows between glazed walls that reconcile the expressionist reflections with the transparency of the Sachlichkeit to expose universal truths at the service of the new industry of glass, and this geometrical seed bears fruit in three successive constructions by Mies van der Rohe: the Barcelona Pavilion of 1928-29, which uses opulent materials and exquisite proportions to raise a manifesto of the new language, making icons out of the onyx wall, cruciform pillars, majestic armchairs, and Kolbe’s Morgen; Villa Tugendhat in Brno of 1928-30, which lends domestic plausibility to the open plan through a rigorous choreography of furniture pieces and meticulous detailing; and the house at the Berlin exhibition ‘Die Wohnung unserer Zeit’ of 1931, which radically materialized the interior and exterior fusion prefigured in the Brick Country House of 1924.

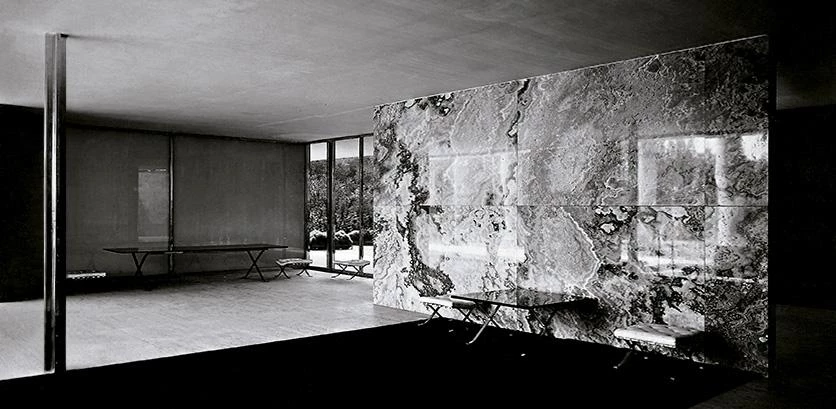

Just as Lilly Reich was co-author of the Glasraum (and did Café Samt & Seide with Mies that same year at the Berlin show ‘Die Mode der Dame’), she collaborated in the other three projects and her influence was felt everywhere: not so much in the omnipresence of glass as in the increased importance of furniture and claddings, the relish for the rich tactility of silk, leather, and velvet – in Barcelona she would again with Mies produce the ‘Deutsche Seide’ exhibition in the Silk and Velvet section of the Palace of Textile Arts –, and the inclusion of sculptural figures as sensual accents in cold abstract interiors.

Muestra de tejidos de seda. Barcelona, 1929

The MR of Stuttgart, the Barcelona, the Tugendhat, and the Brno are four of the mythical chairs designed by Mies for these works, but the sensual quality of their upholsteries is partly attributable to the exquisite severe taste of the designer who became the architect’s personal and professional partner. The materials and colors of the Barcelona Pavilion or the Tugendhat House are so much a part of these works that Philip Johnson, in the first monograph on Mies, shows their importance by including two long lists where travertine, onyx, and green marble from Tinos go with ebony, raw silk, and white velvet, and here again it is impossible not to discern Reich’s fingerprint.

In the Barcelona Pavilion, Mies fused the spatial language of Frank Lloyd Wright with the aesthetic intuitions of De Stijl to create a substantially new architectural language that was received with admiration – Wright himself, normally not given to praise, was quick to acknowledge it, though did try to persuade Mies to “get rid of those damned little steel posts that look so dangerous” – and became part of the heritage of the Modern Movement. Political circumstances in Germany and Europe, alas, did not let this language take root, and Mies could not build anything of note in the following years, which he devoted to teaching at the Bauhaus and to projects and competitions through which he tried to adapt his architecture to the changing ideological and economic scene.

The 15th BEAU (Spanish Biennial of Architecture and Urban Design) will use the Barcelona Pavilion, now attributed to both Mies and Reich, as one of two venues. We mark this by reproducing the text published in a 2019 book that celebrated the Bauhaus centenary.