Twenty years separate the severe, archaic monumentality of the ikastola by Linazasoro & Garay in Fuenterrabía from the pleasant, bright lightness of the nursery school by Eduardo Arroyo in Sondica.

The ballot box needs the school. Not only because so many school buildings become electoral stations on the festive day of voting, but especially because the values an adult expresses on the ballot box come from those a child acquires in school. The acceptance of diversity and tolerant coexistence are not spontaneous civic virtues, but arbitrary and fragile social concoctions that wither if not tenaciously and deliberately nurtured in the family environment, in educational institutions and in communications media. Unfortunately, the cultivation of the democratic spirit is hardly parallel to the cultivation of the national spirit of the old regime, nor to the cultivation of the nationalistic spirit of some current political movements, and the school ends up being a scene of conflict between the illuminist rationalism of mixed race democracy and the identity-oriented romanticism of ethnic nationalism. This caesura between reason and roots also fractures the architecture of the school, perfectly reflecting the ambiguity and ambition of a period’s aspirations.

The height of one meter fifteen distinguishes the child’s world from the adult’s in the Bilbao nursery, neoplastic in the ‘Dutch’ composition of its east facade, and somehow drier in the translucent glass of the opposite face.

In 1978, the year the Spanish Constitution was finally approved, two San Sebastián architects finished an ikastola in Fuenterrabía which became a symbol of the hopes and values of the times. Twenty years later, and coinciding with a Basque election that is particularly significant because it is being held in the wake of the announcement of an indefinite ceasefire, a Bilbao architect has completed a nursery school in Sondica which could well become an emblem of the expectations and priorities of the present moment. Between Fuenterrabía and Sondica lie two decades of political life characterized by the conditional freedom that terror affords, and two decades of cultural life marked by the everyday presence of violence; but two decades, too, of historical mutations in the ideas and cultures spewed out by a planetary economy. Local and global, the two Basque schools illustrate by way of contrast the evolution of Euskadi and the evolution of the world.

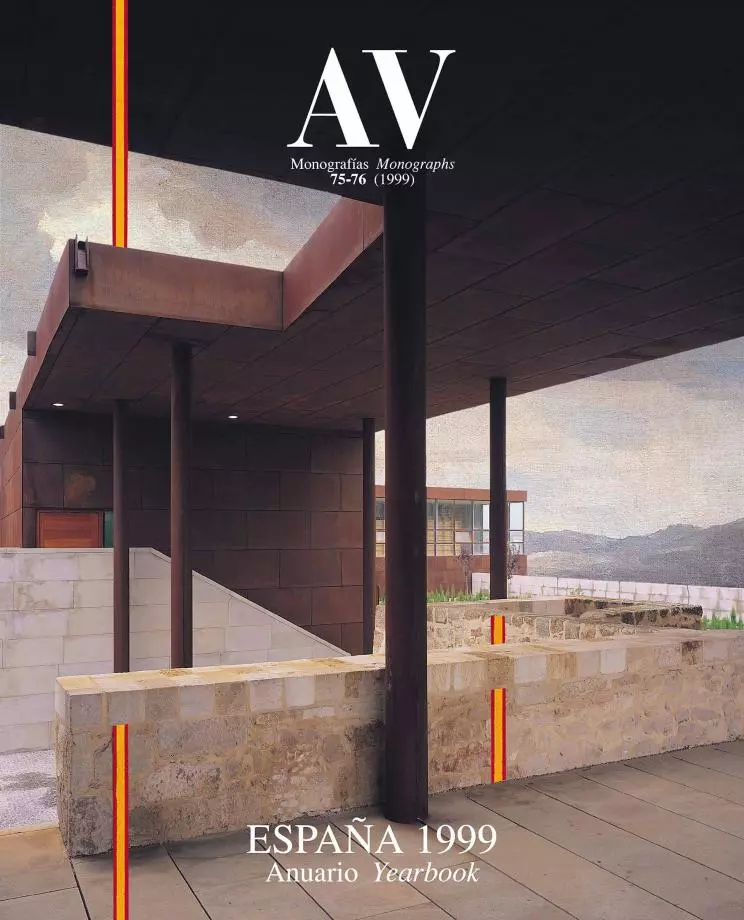

Designed while Franco still lived and built during the critical years immediately following his death, the Fuenterrabía ikastola is a large, monumental, severe construction, strangely archaic in its crude classical rigor and seemingly extracted from the abstract and typological repertoire of French illuminist architects. Its authors Miguel Garay and José Ignacio Linazasoro, then recent graduates heading the culture commission of San Sebastián’s architectural association, interpreted stripped classicism as an anthropological vaccine against modern triviality. In tune with other young European professionals united around the Milanese Aldo Rossi’s Tendenza, their radical method was to look for roots in the architecture of reason, and Linazasoro would effortlessly reconcile his devotion to the anthropologist Caro Baroja with his programmatic defense of classicism. The ikastola would not be all the more Basque because it evoked a regional farmhouse, but because it created a public and institutional field of socialibility, where regulated norms fabricated the collective conscience with a strict and disciplined order.

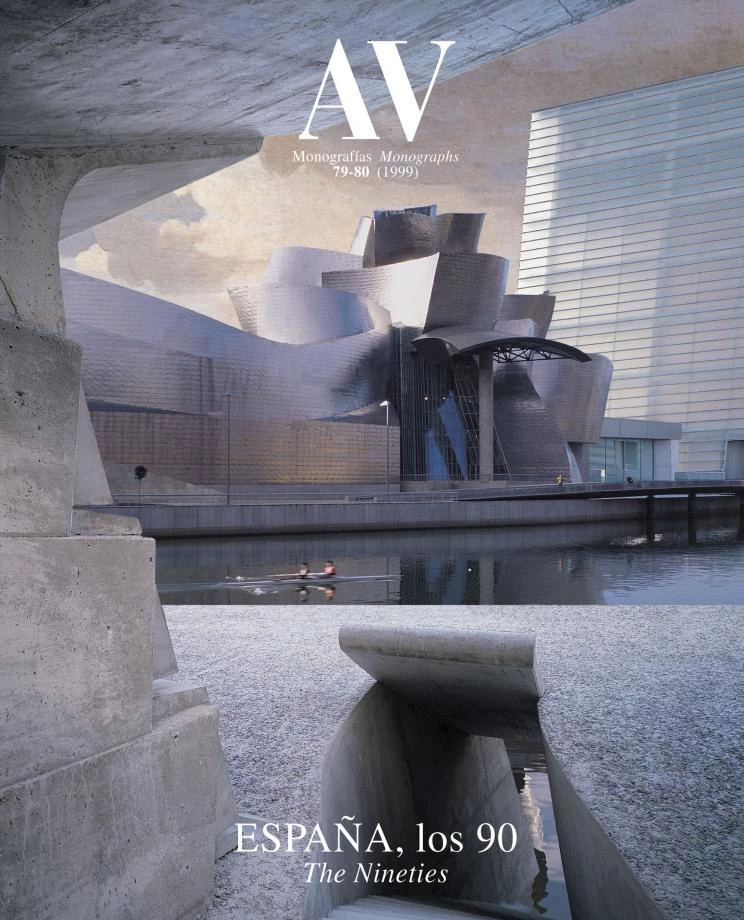

In contrast to the resistant totalitarianism of the ikastola, the Sondica school is a light and pleasant shed with large surfaces of glazing and friendly changing roofs, neoplastic in the ‘Dutch-style’ fragmentation of its east elevation while of a rougher abstraction in the translucent glass of the opposite facade. Its young author Eduardo Arroyo was among the winners of Bilbao’s Abando-Ibarra competition, after a wandering training phase that included the firms of Rem Koolhaas in Rotterdam and Jean Nouvel in Paris, besides a long sojourn on the island of Pascua. Under the inevitable label of ‘Nomad’, and in tune with the modern tradition of the Netherlands, the studio of this lyrical architect tries to bring together technology and anthropology, efficiency and play. Such is the case in this luminous incubator for children from zero to three years old, which is traversed throughout, at a height of 115 cm, by a line that separates the universe of infancy, with its miniature doors and toilets, from the world inhabited by adults, whose gazes glide over the magic floating line.

With no two facades alike in composition and material (recalling the four different facades of the Kunsthal of Koolhaas, which Arroyo had a part in), this infantile greenhouse, whose floor plan is so schematic that the client might well have traced it on the ground with a cane, becomes complex and dramatic with the minute detailing of each vertical plane, and as it gets crowned with a steel bird whose metallic origami gives each classroom a height and light of its own, evoking the slope of the nearby mountains through the slant of the ceilings and prolonging the adjacent fields through the green linoleum of the floors. Here the melancholic search for roots is reduced to the formal and chromatic echo of the landscape, and the insistence on legitimizing reason is nuanced by the unexpected anthropometry of the child. If twenty years ago Fuenterrabía was a paradigm of the culture of struggle that marked the political transition, today Sondica is an admirable sample of the culture of adaptation being fostered by economic globalization: a contemporary of Bilbao’s Guggenheim and San Sebastián’s Kursaal.

The Language of the School

Being so markedly visual, the language of architecture possesses a generality that breaks through conventional frontiers, and architects have a gift for understanding one another independently of the tongue that makes them natural cosmopolites. Thus Garay and Linazasoro’s ikastola of the seventies spoke an architectural Esperanto that was common to all the young professionals then proposing to rebuild the existing European city; and Arroyo’s kindergarten of the nineties uses the lingua franca of the old continent’s contemporary avant-garde. This community of codes has already been extended to the economic field, but not yet to the realm of shared European history. Perhaps the main defect of Franco classrooms was precisely the bias and partiality of the regime’s historical vision, and we cannot be sure that the classrooms of autonomic democracy have remedied such a narrow conception entirely. Now that the continent’s governments are making efforts toward a ‘pedagogy of the euro’, they ought to pay similar attention to the ‘pedagogy of European history’, difficult as it is to believe that the economy can alone be the mortar of our integration. Meanwhile, the spontaneous mingling of peoples, tongues and histories continues its inexorable and happy course, and at Madrid’s architecture school for one, where both Linazasoro and Arroyo now teach, the growing presence of European students makes conversations overheard in corridors a voluntary, enjoyable and hopefully irreversible Babel.

The way from one school to another charts an architectural voyage, stretching from Milan to Rotterdam, as well as a social voyage, leading from the agitation of the end of a dictatorship to the confident aplomb of a mature democracy. Jon Juaristi assures us that the eggs of the ETA serpent were incubated in a school, Bilbao’s Escolapios. Contemplating the transparent geometries of the Sondica kindergarten, one cannot help thinking that only tolerance, pleasure and respect can be incubated in such warm and luminous volumes. Some will smirk at such optimism, but architecture is a serious game. If the Basques have a path leading to a star, the route certainly passes through the sunny ballot boxes where their children are incubated.