Milan hasn’t reinvented the expos, but has organized one better than many. The visionary original concept of Jacques Herzog – together with Italian architect Stefano Boeri, British urbanist Ricky Burdett, American green architect William McDonough and the Slow Food movement founder Carlin Petrini – proposed doing without pavilions as monuments of national pride and focussing on the exhibits, but this radical transition from containers to contents was finally thwarted, and the Expo ended up featuring the usual mix of ephemeral constructions that vie to lure visitors. However, the initial concept of a long shaded avenue (rounded off with a smaller perpendicular axis) that gives access to most of the plots has been maintained in the final design, and both this clear arrangement and the refrained architecture of most of the pavilions makes this universal expo worthy of critical attention.

Despite the bad omens that preceded its opening, surely inseparable from this type of event, and that went from the usual political disagreements, financial troubles and construction delays to the most serious accusations of corruption in the awarding of contracts and property speculation around the site – aside from the urban vandalism that stole the headlines from the Expo the day of its opening –, Milan has finally been able to offer a festive and friendly spectacle where almost a hundred pavilions compete to seduce with their architectures and their content, which by the way interpret freely the exhibition’s motto: ‘Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life.’ In fact, just a few of them tackle the agricultural and energy dilemmas posed by the challenge of feeding a planet in the midst of population explosion, while most pavilions ultimately embrace the hackneyed path of national products and regional cuisine.

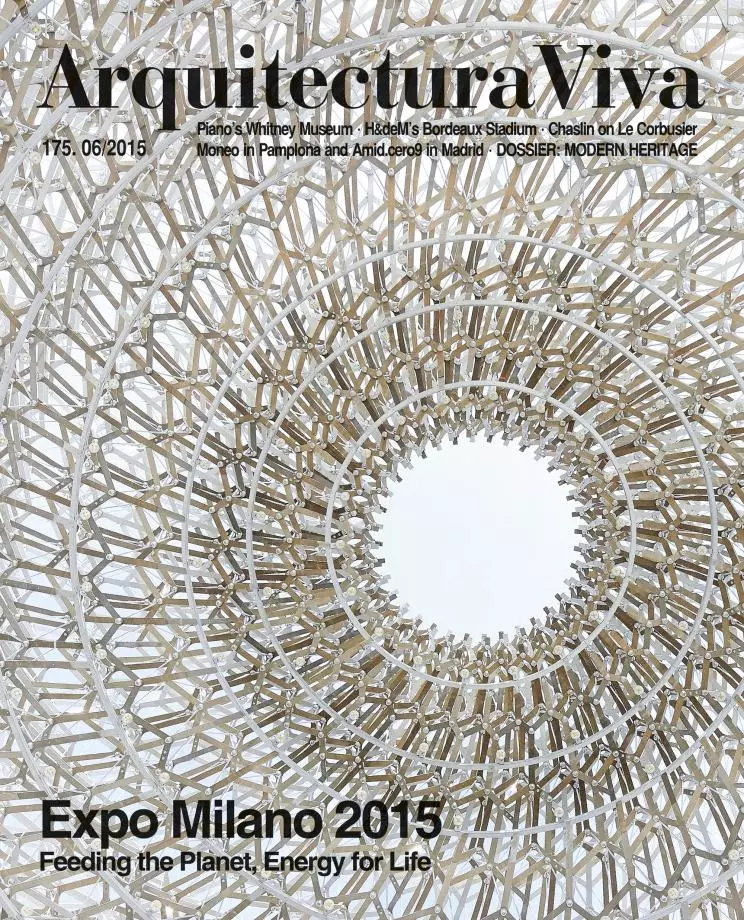

Architecture, for its part, is as diverse as the selection of pavilions included here shows, but the site plan – with a cardus and a decumanus whose light canopy evokes Milan’s emblematic galleria –, along with the restraint of more austere times, has helped to cleanse the grounds from many of the extravagances usually found in expos, and the general impression is serene rather than bustling. From the concise sobriety of Spain’s pavilion to the sturdy elegance of Chile’s, passing through the technical lyricism of that of the UK or the warped lightness of China’s, the Expo’s ephemeral structures are perhaps simply, as Herzog has said, “the same kind of vanity fair that we’ve seen in the past,” but this fair is more orderly than most, and its main axis is rounded off with three exact wood sheds designed by the Swiss architect for Slow Food: a residue of its difficult beginnings that can be also a critical inspiration for the future of these events.