Cheap oil is at once temptation and opportunity: the temptation to preserve a land use and technical model that consumes huge amounts of energy, because the incentives associated with scarcity and shortage have vanished; and a historic opportunity to change an energy policy that stimulates waste and accelerates climate change through carbon emissions. The drop of fossil fuel prices – which

will be lasting, according to experts – is a disaster for the producing countries, whose internal convulsions furthermore alter delicate geopolitical balances; but it is a blessing for those lacking resources of their own and that, like Spain, must import most of the energy they consume. Whether we should take advantage of this bonanza to keep things as they are or, on the contrary, use it to promote the transition towards renewable energies is a key dilemma of our time.

Technological advances and fracking – besides promoting energy self-sufficiency in the United States and the resulting turn in its foreign affairs policy, in the Gulf and other regions – have certainly diminished the feeling of urgency associated with other oil crises; however, the scientific consensus that links global warming to the consumption of fossil fuels, and that in the United Nations Climate Change Conference held in Copenhagen in 2009 failed to promote efficient agreements to fight this dramatic process, seems to have triggered enough alarm among world populations and leaders so as to enable us to forecast a more satisfactory result in the summit to be held in December 2015 in Paris, where binding commitments to reduce greenhouse gases are expected to be made, and in this occasion also

by the major powers, which until now had eluded their responsibility.

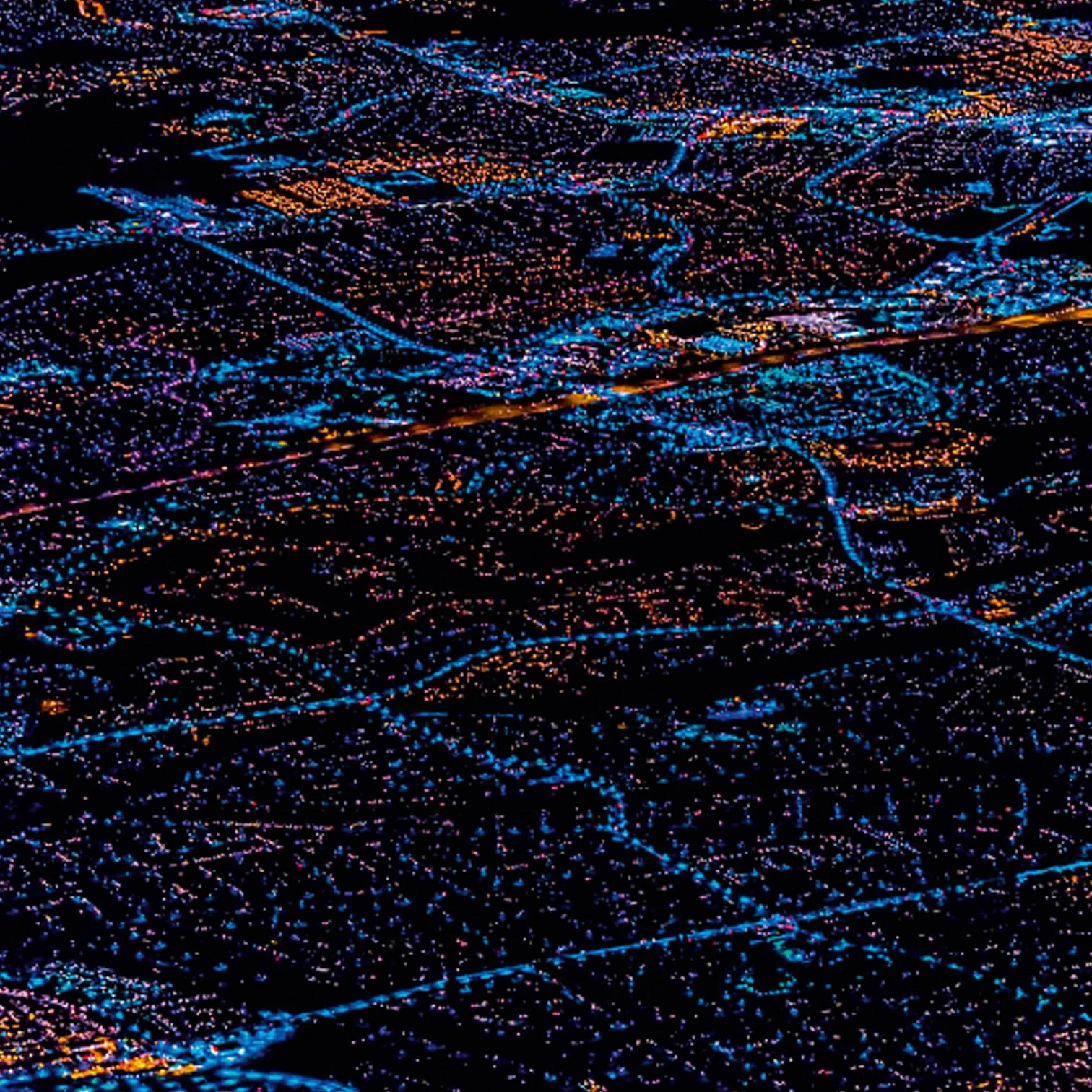

If the energy debate must inevitably be linked to the one on climate, it is also important to connect it to the sphere of architecture and urban planning. Buildings do in fact consume very large amounts of energy, which can be significantly reduced through insulation, orientation, shading, or thermal inertia, not to mention by altering the critical relationship between surface area and volume enclosed. But even more decisive is on this account the urban model, where density and compacity offer clear advantages in our latitudes, and are also important to reduce energy transportation costs; something that becomes particularly relevant on the scale of the territory, which acts as the stage for the sleepless movement of people and goods in contemporary societies. Architecture and urbanism have therefore a leading role in the energy and climate debate, perhaps the greatest challenge that our generation faces today.