Stage and archive, the magazine is above all an imaginary museum. Placing this issue under the equivocal advocacy of André Malraux – whose mythical portrait is reproduced tiny in the presentation –, we propose recalling to what extent a publication like this one uses texts and photographs to be at once showcase and record of the evolution of architecture, so that it can be described as a musée imaginaire. We have discussed Malraux before – in Arquitectura Viva 63 and AV 104 –, but we would have to wait for the book by Walter Grasskamp, first published in German in 2014 and edited in English with the title The Book on the Floor by the Getty Research Institute in 2016 – reviewed in Arquitectura Viva 192 –, to discover the details behind the extraordinary photograph taken in 1954 by Maurice Jarnoux for Paris Match, and that is still the best visual representation of the mind of the writer, standing in the photograph with the elegant stance of a cultural heroe, before the pages of the art album Des bas-reliefs aux grottes sacrées, one of the volumes of his trilogy Le musée imaginaire de la sculpture mondiale.

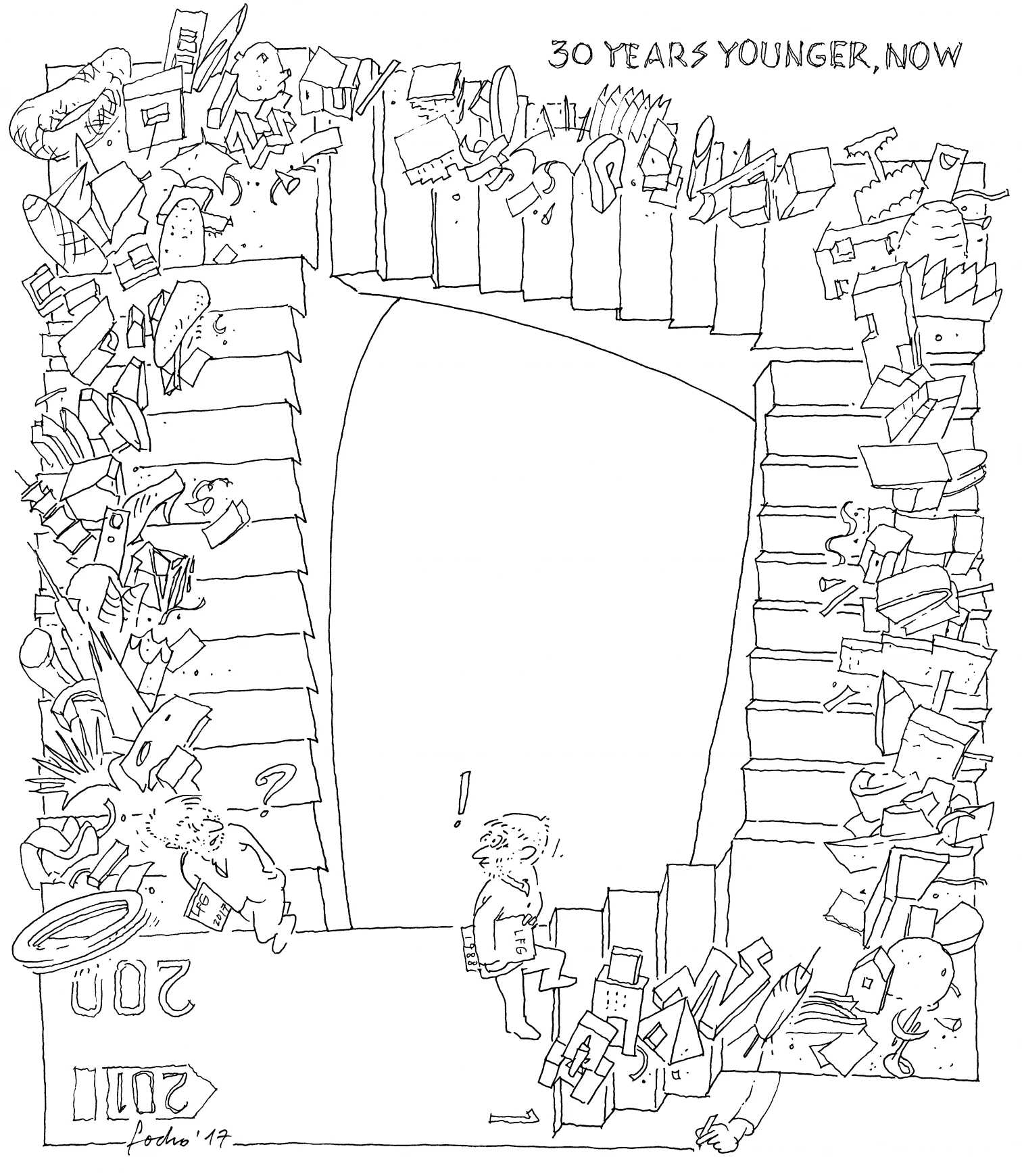

Over the last three decades, this magazine has modestly ambitioned to be an imaginary museum of contemporary architecture, something that Focho’s cartoon sums up well on the cover and page 4, where the dizzying formal carousel of these years appears as an endless number of models chaotically placed on the steps of a staircase that bewilderingly takes us back to the starting point, so the succession of ideas and intentions over time is abbreviated in a sequence of forms whose chronological archive reveals nothing but an almost caustic skepticism, underlined by the disappearance of the draftsman, whose hand appears only to complete the volume of the staircase, in a second homage to Escher. There is a clear contrast between the stylish heroism of Malraux, relaxedly lording over the pages neatly spread on the floor, and the double figure perplexed under the carnival of forms that the staircase unfurls in a circular time.

Arquitectura Viva devoted its first issue of the year 2000 to fifty figures of the century then coming to an end, and Focho gathered all of them – as well as a Wally hiding in the crowd, giving a light touch to such solemn crop of celebrities – in a somber room where the architects stood under the shaft of light from a lamp to be portrayed by the draftsman, who had the editor by his side in the role of iconographic director of the endeavor. Together, the nocturnal stage of yesterday and the diurnal archive of today compose the two faces of the imaginary museum of this magazine, where both the authors and their works are displayed with attentive curiosity and registered in careful detail, a painstaking effort and a perhaps useless passion that Focho’s cartoons express with smiling skill.