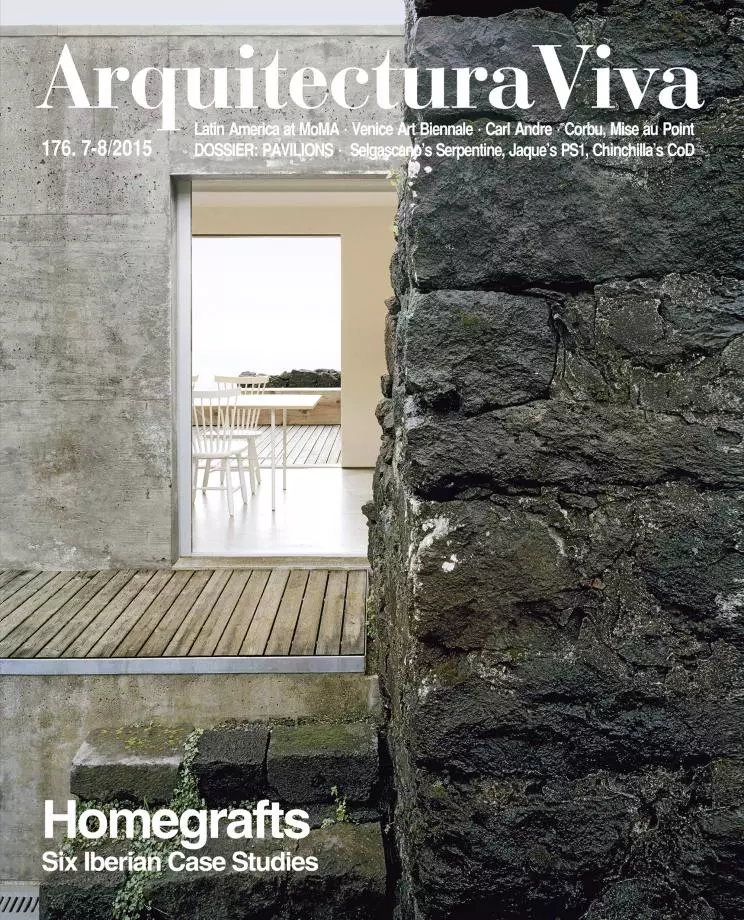

Dead stones are very much alive. We think about ruins as residues or traces of past activities, and fail to appreciate the fertility of these material remains, which store both the thermodynamic capital of their transport, preparation, and assembly, and the information capital of their climatic, technical, and topographic interpretation. The effort and knowledge of those before us is stored in this frozen heritage, which can flourish and come back to life when we graft new elements on its inanimate walls, dry trunks or beheaded stumps that give physical strength and symbolic patina to the tender shoots of recent construction. New architecture is rooted in the existing, and the choreographies of the everyday take place in the sheltering shadow of the past, which nurtures with memory the renovated spaces and recommenced biographies of those who try to inhabit the land without succumbing to the amnesia of the tabula rasa.

The same process is experienced by cities in their endless mutation, raveling and unraveling with every historical convulsion, reconstructing their buildings with recycled materials, demolishing and raising their physical tissue in a tirelessly working loom of Penelope, blurring traces and foundations that end up buried and forgotten to later sprout impetuously from that hidden seed, and growing geologically through strata piled up as the slime of riverbeds, so that every settlement rests on the footprint of previous ones. This material stratigraphy is, indeed, an archaeological register of human life, and its reading permits documenting rises and falls, periods of economic prosperity and times of demographic contraction, moments of splendor and instants of devastation; but it is, above all, an essential support on which to graft the renewed skin of the city, the structures that each generation raises as its residence on Earth.

And no better place to show organic continuity than the domestic realm, because it is precisely there where the biological relationship with the natural environment becomes more explicit: the house is after all the place for feeding and evacuation, for cold and heat, for affection and routine. By grafting the new on the existing we insert our precarious life in the lives of others, camouflaging our inevitable mortality in the consoling fiction of a chain with no broken links, and giving our fleeting journey deep roots and added memory. While many will see the physical presence of the past in the spaces of the present as a fake pedigree or an acquired genealogy that only hopes to give distinction to a trivial existence, these homegrafts reconcile us with our ephemeral condition, offer us the equivocal mirage of a dialogue with absent forebears, and remind us that we are just the dust of dead stars.