Synopses

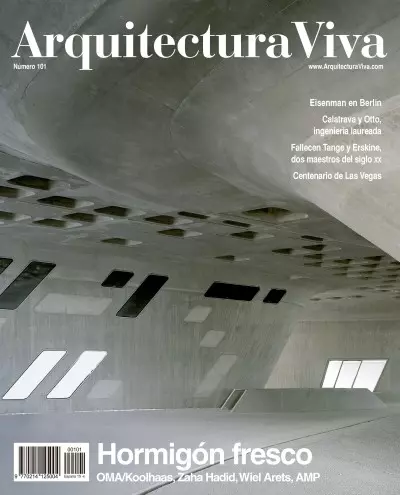

Cool Concrete. Discovery or invention, the mixture of cement, water, sand, gravel and steel is transformed into reinforced stone, taking the shape of its mold, whichever it is. From its massive Roman origins to the recent inclusion in the mix of metallic or synthetic fibers which turn it into a supermaterial, through the improvements carried out by the French engineers during the 19th century and the decisive development of prestressing, concrete is currently the most widely used construction material in the world. Sophisticated or vulgar, sculptural or standard, this archaic product is also a material of the future.

Contents

Jean-Louis Cohen

The Saga of Concrete

A Material of Modernity

Justo Isasi

Liquid Stone

An American Symposium

Julio Martínez Calzón

A Material of the Future

High Tech Concrete Today

Cover Story

Formwork Pieces. Four recent constructions clearly show how concrete is capable of adapting to the language of different authors. Like a geometric meteorite, the Casa da Música in Porto, designed by OMA, lifts in unstable balance a faceted volume that contains an auditorium of classical proportions; the Phaeno Science Centre, built by Zaha Hadid in Wolfsburg, challenges the laws of gravity with its free-flowing spaces and oblique walls; the university library of Wiel Arets in the campus of Utrecht is a stern box of printed concrete and serigraphed glass in whose interiors the book deposits hover over public voids; and the Congress Center of AMP in Tenerife Sur defines a rocky and coarse landscape underneath the metallic wave of its roof.

Architecture

OMA/Rem Koolhaas

Uncut Diamond

Casa da Música, Porto

Zaha Hadid

Physical Phenomenon

Science Centre, Wolfsburg

Wiel Arets

Enlightened Nature

University Library, Utrecht

AMP/Artengo,Menis,Pastrana

Urban Megalith

Congress Center, Tenerife

Views and Reviews

Laureate Engineering. The union of architecture and technology has in Santiago Calatrava and Frei Otto two singular examples: if the Valencian is also sculptor and draftsman, the German draws inspiration from the organic.

Art / Culture

Alexander Tzonis

Calatrava, Technique and Motion

Joan Sabaté

Otto, Light Nature

Goodbye to Two Masters. Kenzo Tange and Ralph Erskine have passed away at over ninety years. The former combined symbolism and modern technique, and the latter defended community participation and respect for nature.María Teresa Valcarce

Tange, Japanese Monument

Carlos Verdaguer

Erskine, Eternal FlameConcrete Stories. A French chronicle studies the pâte de pierre from its origin to its transformation into a conventional technique; and a collection of recent works displays the different uses of this universal material.

Focho’s Cartoon

Thom Mayne

Various Authors

Books

Recent Projects

Pure Cement. Three examples bear witness to the Alpine taste for the naked texture of concrete: painted red in order to give identity to a stratified block for a medical center inYverdon-Les-Bains; a showcase for itself in a construction consulting center in Munich; and bare to the point that it shows the gravel in a guest pavilion beside a villa by Semper in Castasegna.

Technique / Style

Devanthéry & Lamunière

Psychiatric Clinic

Hild & K

Construction Center

Miller & Maranta

Villa Garbald Extension

To close, Sin City celebrates its centenary. This small village in the middle of the Nevada desert, where the railway arrived in 1905, and that became the uninhibited capital of gambling in the fifties, was enthroned by Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour in the seventies as a genuinely American cultural phenomenon. Today, its greatest sin is triviality and loss of authenticity.Products

Bathrooms, LCD Monitors

English Summary

Cool Concrete

Stanislaus von Moos

The Future is in the Desert

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Cool Concrete

Old concrete is young. A material created in the 19th century following the archaic model of traditional mortars, and developed in the 20th up to spectacular levels of technical innovation and architectural daring, has reached the 21st as a structural and constructive resource radically renewed by scientific developments and aesthetic searches. Hard when it sets and fluid when unset, this paradoxical material well deserves to be known as ‘liquid stone’, because the oxymoron summarizes its double condition: dry and wet, solid and soft, rough and smooth. In the title ‘Hormigón fresco’, its still malleable state alludes to the very recent completion of the works published, metaphorically capable of bearing the imprint of marks; but it also refers to their inventive and unexpected nature, as they make the most of the expressive possibilities of concrete without rigidities or preconceptions.

The contradiction inherent to its two consecutive states – the humid sensuality of the mix, slippery as a stream or moldable like potter’s clay, in contrast to the unaltered boldness of set cement – also offers a reluctant illustration of its two-fold professional and public character: bright banner of paleotechnic constructive culture or dark symbol of speculative building; vehicle for the heroic engineering of bridges, towers and tunnels or instrument for the abusive development of cities and coasts; and essential tool for architects with sculptural interests and a taste for texture or unfriendly context for the advocates of dry and light construction. Between blob and bunker, concrete flows steadily through contemporary landscapes where it offers material gravity and thermal inertia, structural verbosity and mechanical inertia, volumetric expressiveness and artistic inertia.

It has been a long way from the wise ramblings of Perret, the calculated intuitions of Freyssinet and the syntactic inventions of Le Corbusier. This path, which has had remarkable milestones with Nervi, Saarinen, Niemeyer or Tange, and which has been weaved as well by extraordinary Spanish engineers and architects, from Torroja and Candela to Fisac or Calatrava, goes today through places that would be unfamiliar to many of its former figures: emotion is more important than analysis, surfaces are more carefully detailed than structures, and chemistry comes before physics. Few of the significant names of concrete during the 20th century would describe their works as inhabited sculptures, and yet this is the label that best befits the projects that cross the threshold of the 21st century: the great technical advances of this hour have been placed at the service of formal innovation and aesthetic styling.