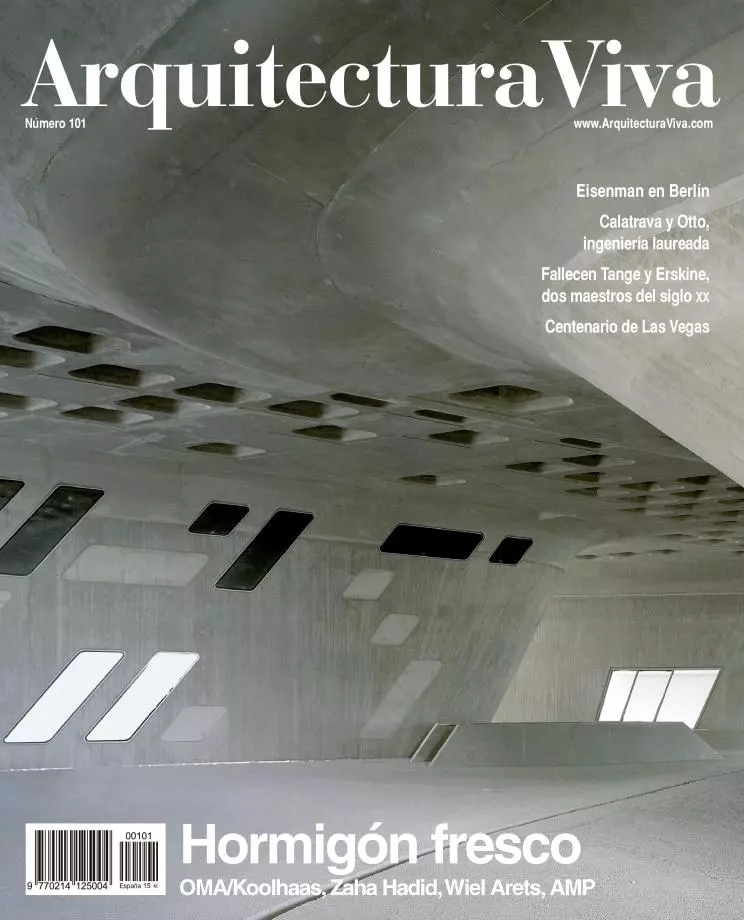

Old concrete is young. A material created in the 19th century following the archaic model of traditional mortars, and developed in the 20th up to spectacular levels of technical innovation and architectural daring, has reached the 21st as a structural and constructive resource radically renewed by scientific developments and aesthetic searches. Hard when it sets and fluid when unset, this paradoxical material well deserves to be known as ‘liquid stone’, because the oxymoron summarizes its double condition: dry and wet, solid and soft, rough and smooth. In the title ‘Hormigón fresco’, its still malleable state alludes to the very recent completion of the works published, metaphorically capable of bearing the imprint of marks; but it also refers to their inventive and unexpected nature, as they make the most of the expressive possibilities of concrete without rigidities or preconceptions.

The contradiction inherent to its two consecutive states – the humid sensuality of the mix, slippery as a stream or moldable like potter’s clay, in contrast to the unaltered boldness of set cement – also offers a reluctant illustration of its two-fold professional and public character: bright banner of paleotechnic constructive culture or dark symbol of speculative building; vehicle for the heroic engineering of bridges, towers and tunnels or instrument for the abusive development of cities and coasts; and essential tool for architects with sculptural interests and a taste for texture or unfriendly context for the advocates of dry and light construction. Between blob and bunker, concrete flows steadily through contemporary landscapes where it offers material gravity and thermal inertia, structural verbosity and mechanical inertia, volumetric expressiveness and artistic inertia.

It has been a long way from the wise ramblings of Perret, the calculated intuitions of Freyssinet and the syntactic inventions of Le Corbusier. This path, which has had remarkable milestones with Nervi, Saarinen, Niemeyer or Tange, and which has been weaved as well by extraordinary Spanish engineers and architects, from Torroja and Candela to Fisac or Calatrava, goes today through places that would be unfamiliar to many of its former figures: emotion is more important than analysis, surfaces are more carefully detailed than structures, and chemistry comes before physics. Few of the significant names of concrete during the 20th century would describe their works as inhabited sculptures, and yet this is the label that best befits the projects that cross the threshold of the 21st century: the great technical advances of this hour have been placed at the service of formal innovation and aesthetic styling.