Erasmus was born in Rotterdam and died in Basel. The wandering humanist who best symbolizes European cultural unity traced his vital arc between two cities that now tense up the architectural debate: Rotterdam, the northern seaport where the Dutch Rem Koolhaas and his Office for Metropolitan Architecture have been the ferment-ing agent of a young generation that engages in formal subversion by means of a paradoxical pragmatism; and Basel, on the border between Switzerland, Germany and France, where the team formed by Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron is the standard-bearer of a general sensibility whose coordinates are matter and rigor. The Erasmus program, thanks to which so many youngsters are able to carry out a part of their studies in other European countries, tried to complement the economic convergence that has given rise to the euro with a parallel process of cultural convergence. Fortu-nately, however, the single currency does not generate a single thought, and the interaction induced by increased communication and exchange has not stifled the vigorous individual personalities of Europe’s cities. At the threshold of a new century, two of them represent the poles between which beats the torn heart of architecture.

Rem Koolhaas from Rotterdam (Utrecht Educatorium, above) and Herzog & de Meuron from Basel (hospital pharmacy, below) extend today a debate initiated by Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe.

Rotterdam is the city of Rem Koolhaas, a bril-liant, abrasive, megalomaniac figure whose Delirious New York two decades ago wrung architec-ture’s neck to make it look in another direction, and whose three kilograms of S,M,L,XL three years ago slapped its head to frighten it out of its lethargy. The son of an important writer and himself one, this 54-year-old architect has made it his mission to wrench modern tradition as much through his books as through his buildings, which with exquisite perversity combine revolutionary Russian constructivism with bureaucratic American utilitarianism in a circle that also features Le Corbusier, Salvador Dalí and science-fiction comics. Such shock treatment has not been painless, and there are those who fear for the survival of the patient with a broken neck and fractured skull. Still, Koolhaas’s warped floors and surreal effects have become a reference for the experimental faction of European architecture.

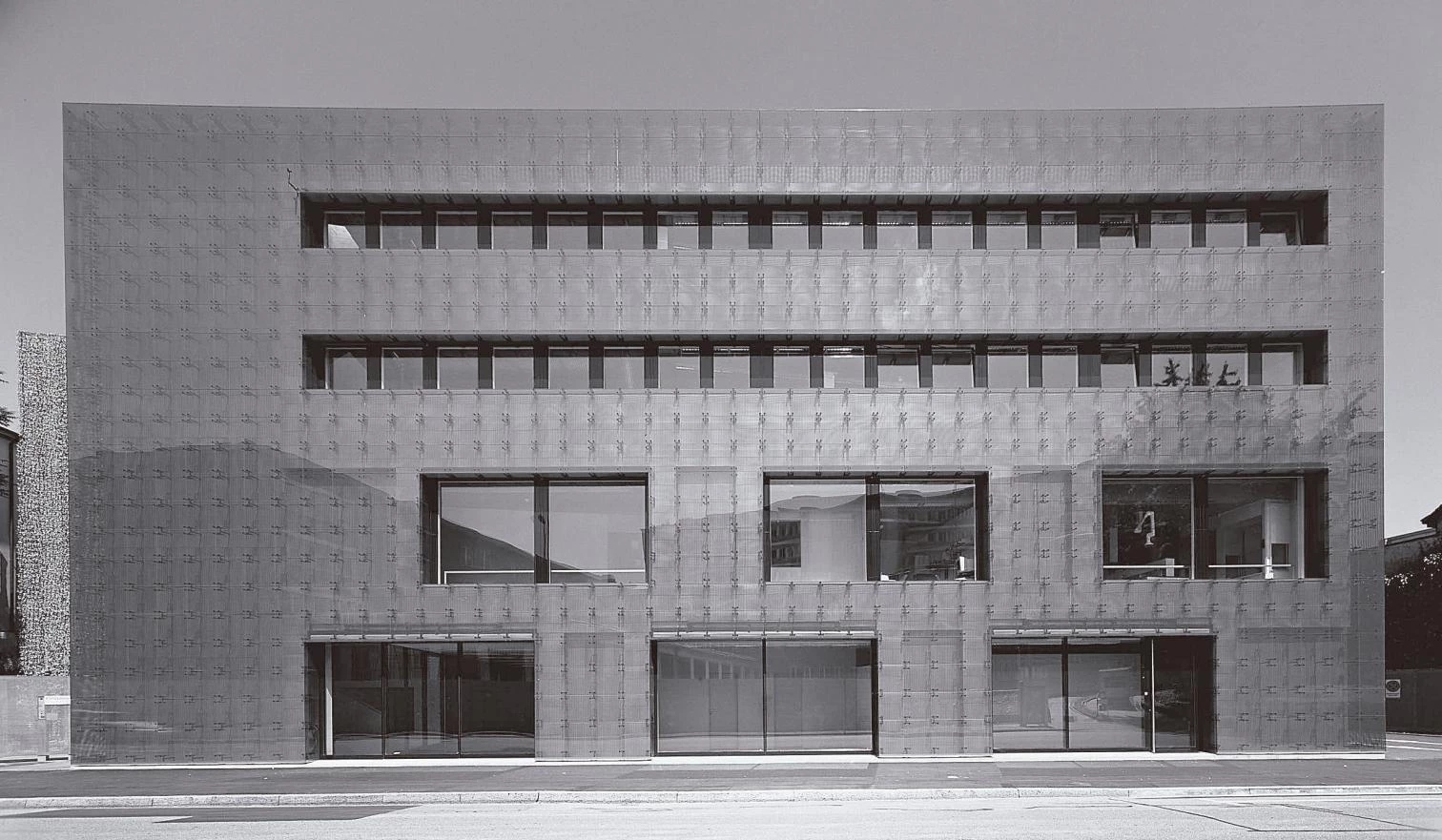

Basel, in its turn, is the city of Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, who, both 48 and with twen-ty years of professional practice behind them, have together built an artistic corpus that in consistence and rigor is unrivalled in their generation. Disci-ples of the Italian Aldo Rossi and the German Joseph Beuys, the Swiss partners have time and again merged the geometric discipline of architecture with the unpredictable emotion of art, and this union of visual order and tactile seduction has brought forth a sequence of impeccable, dramatic buildings. From the railway signal box screened with copper to the recent California winery wrapped in basalt, each of their works combines an efficient skeleton with a fascinating material skin, and it is perhaps the meeting of rational function and emotive envelope that produces the cold sensuality they have become admired and imitated for, not only in minimalist German-speaking Switzerland but also in other parts of architectural Europe that yearn for exactitude.

The rhetorical schism between Rotterdam and Basel revives at the close of the century a debate that has taken up a good part of it, with Le Cor-busier and Mies van der Rohe as protagonists. On one hand was the formal imagination and propagandistic eloquence of the master from La Chaux-de-Fonds; on the other, the constructive meticulousness and aphoristic laconism of the master of Aachen. Between them a creative tension was established which with its dialectic combustible has fueled the most fertile dilemmas of our times. In his futuristic extravagance Rem Koolhaas has brought Le Corbusier’s demiurgic ambition and formal in-ventiveness to surreal extremes, while Herzog & de Meuron have unprecedentedly transferred Mies van der Rohe’s material elegance and geometric rigor to the realm of the conventional, trivial and every-day. And between both poles – audacious Holland and refined Switzerland – sways the attention of the continent’s architects.

Authors of the Liner Museum in Appenzell (above) and the signal box in Zurich (below), Gigon & Guyer design with a geometric and material rigor close to that of their fellow Swiss Herzog & de Meuron.

But in the Iberian Peninsula that the erudite Erasmus did not care to visit (non placet Hispania, he who roamed the continent from Louvain to Cam-bridge and Paris to Rome had only that to say to Cardinal Cisneros’s invitation), young architects pay more attention to the Basel of his death than to the Rotterdam of his birth, and prompted by a mix of stubborn modernity and cautious abstracion, they feed on Swiss boxes more than they partake of Dutch folds. As verified in the recent Salamanca gathering of our latest pool of professionals, convoked by Rafael Moneo and Álvaro Siza under the shadow of an Erasmist philosopher and a blind musician, current peninsular architecture looks in only one direction. “When north wind and south wind clash”, to quote a verse of Fray Luis de León that was mentioned in the meeting, Iberians are none too bothered, having already decided which is the dominant wind: that which blows from Basel.

With projects like the Villa VPRO in Hilversum (above) and the two-family house in Utrecht (below) the MVRDV team leads the youngest Dutch generation, heir to the pragmatism and formal freedom of Rem Koolhaas.

Hybrid Generation

The architecture of the youngest Europeans is no-madic and hybrid. The new generations of professionals are cosmopolitan in training, and omnivo-rous in their ecumenical appetite for ideas and forms. After stints in the offices and cities of the moment, they tend to settle down in mixed and multilingual professional marriages. Such is the case of the two next-generation teams that best represent the relieving of Holland’s Koolhaas and Switzerland’s Herzog & de Meuron. The Rotterdam archi-tects Winy Maas, Jacob van Rijs and Nathalie de Vries, all from the school of Delft, joined hands in 1991 to form MVRDV, now the Netherlands’ most exportable acronym thanks to buildings like the WoZoCo apartments in Amsterdam and the VPRO television network offices in Hilversum; Maas trained under Koolhaas at OMA, and Van Rijs and De Vries spent time in the Barcelona studio of Elías Torres and José Antonio Martínez Lapeña. The Swiss partners Annette Gigon and Mike Guyer graduated from Zürich’s ETH in 1984 and set up practice in the same city in 1989, designing works like the Davos, Winterthur and Appenzell museums or the dwellings in Kilchberg, which have made them the leading duo in the young architecture of German-speaking Switzerland; but before this Gigon completed her training in the Basel firm of Herzog & de Meuron, and Guyer completed his in the home of the rival paradigm, Rem Koolhaas’s Office for Metropolitan Architecture. The swords of Rotterdam and Basel may be raised and ready for the duel, but there are those who do not renounce a plural apprenticeship and an assorted diet.