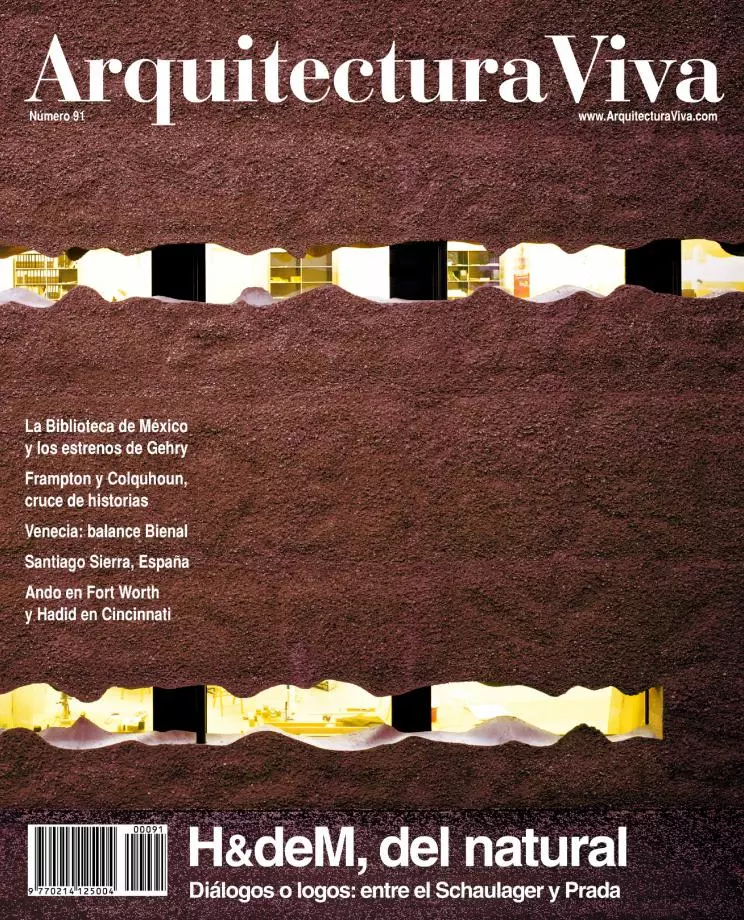

Herzog & de Meuron cook over a low flame, and every now and then take out all the dishes at once. This is what happened during the first half of 2003, that aside from seeing them win the competitions for the Beijing Olympic Stadium and the Hamburg Philharmonic, or present the final project for the Fundación La Caixa in Madrid, has been marked by three exceptional inaugurations: after a warm up, February celebrated the opening of the Laban Dance Centre in London, a translucent volume of soft inflections and watery chromatism in a run down neighborhood by the Thames, and of such exquisite finish and intelligent interpretation of the program that it has deserved the Stirling Prize, the highest distinction in Britain, for the first time awarded to a foreign architect; May saw the inauguration of the Schaulager in Basel, a colossal warehouse and exhibition space for art, carried out with abrupt perfection and tactile fascination in an industrial area of the town for a major collection, and whose typological novelty and subversive language set it forth as an alternative to the Guggenheim model; and June witnessed the launching of the Prada store in Tokyo, a large glazed volume wrapped in turgid lozenges that combines Bruno Taut with Pierre Chareau, while exploiting the opportunity of the fashion showcase to take to the limit a spatial and perceptive exploration at the service of bodies, clothes and identities.

This low flame which they like to describe with the terms research and dialogue – presenting the office as a laboratory where the processes of nature are reproduced – immediately evokes the image of the alchemist endeavoring to transform with his retort everyday lead into the gold of art, an inescapable reference within the context of a town so associated to the pharmaceutical industry as Basel. But this Swiss city on the border with France and Germany is also a precinct of humanist tradition, a stronghold of legendary commercial wealth, and a neoclassic milieu of strict conservatism that repeatedly showed its reluctance towards modernity. No matter how illegitimate it may be to establish an excessive link between architect and city, the stubborn rooting of Herzog & de Meuron in Basel makes one wonder whether their severe and rigorous work, harsh even in the expression of pleasure, may not come from the anachronism of that civic culture. The deliberate archaism of their approach can, indeed, go back to the old romantic humus of the Germanic universe, as happens with their exaltation of mythical nature; but in their criticism of the self-satisfied optimism of modernity there is also something of the controversy of the times of Bismarck between faustic Berlin and reluctant Basel, in such a way that we would believe to be hearing the echoes of the historical debate between Ranke and Burckhardt in the interrupted dialogue that Rem Koolhaas and Jacques Herzog maintain through words and projects.