The flat Netherlands have reached a peak. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, a sister company of The Economist which rates the business environment of countries, the Netherlands today are at the top of the list. In this league table, which uses indicators like market potential, tax and labour-market policies, infrastructure skills and political background, the most privileged places tend to be occupied by Anglosaxon or Scandinavian countries, along side the Asian city-states, Singapore and Hong Kong. In fact, the latter headed this capitalist rank for several years, but the return of the British colony to China caused her to slump down to the temperate positions of the Latin countries, and the Dutch capitalised on the situation to place themselves firmly at the peak of economic arcadia. In the next five years, there will not be a better place in the world to do business.

The business-friendly economy of this country, the most horizontal, the most artificial and the most densely populated on the European continent is not a metaphor for the inventive versatility of its latest architecture, but rather the physical and institutional support on which the landscape of Holland is built. The exceptionally dynamic economy and building industry is accompanied by a deregulation of both business and territory. And it is in this yet undefined ‘new frontier’ where the most innovative proposals of the young Dutch architects are being made. Many of them exhibit an extreme pragmatism, to the point of reproach from the generations who understood modernity as an ethical committment; but others push the opportunistic adaptation to such surreal limits that their projects become a cynical satire of the contemporary world.

In his Stultitiae Laus, Erasmus of Rotterdam mocked “those who were anxious to build houses, suddenly changing the round to the square, and the square to the round.” Five centuries later, the architects from his native city –who have overtaken the more cautious in Amsterdam in the struggle for the intellectual leadership of the Netherlands– preach the gospel of congestion to critical acclaim, subverting convictions and traditional approaches to enthusiastically advocate ‘bigness’ and high density. From OMA´s SMLXL to MVRDV´s FARMAX, and from Rem Koolhaas´s ‘paranoid-critical’ juxtapositions to the surreal superpositions of his disciple Winy Maas, the doctrine of the cadavres exquis of Rotterdam –that swings between the ironic elegance of West 8 to the mediatic hallucinations of NOX– deserve another Erasmus to compose a new Stultitiae Laus dedicated to those that the humanist called wise fools.

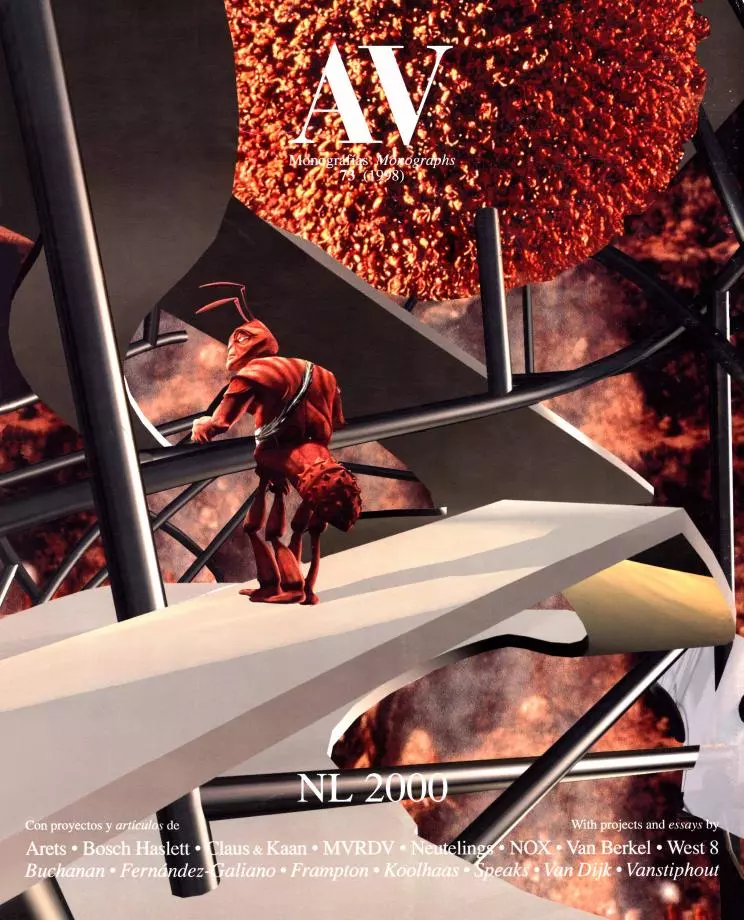

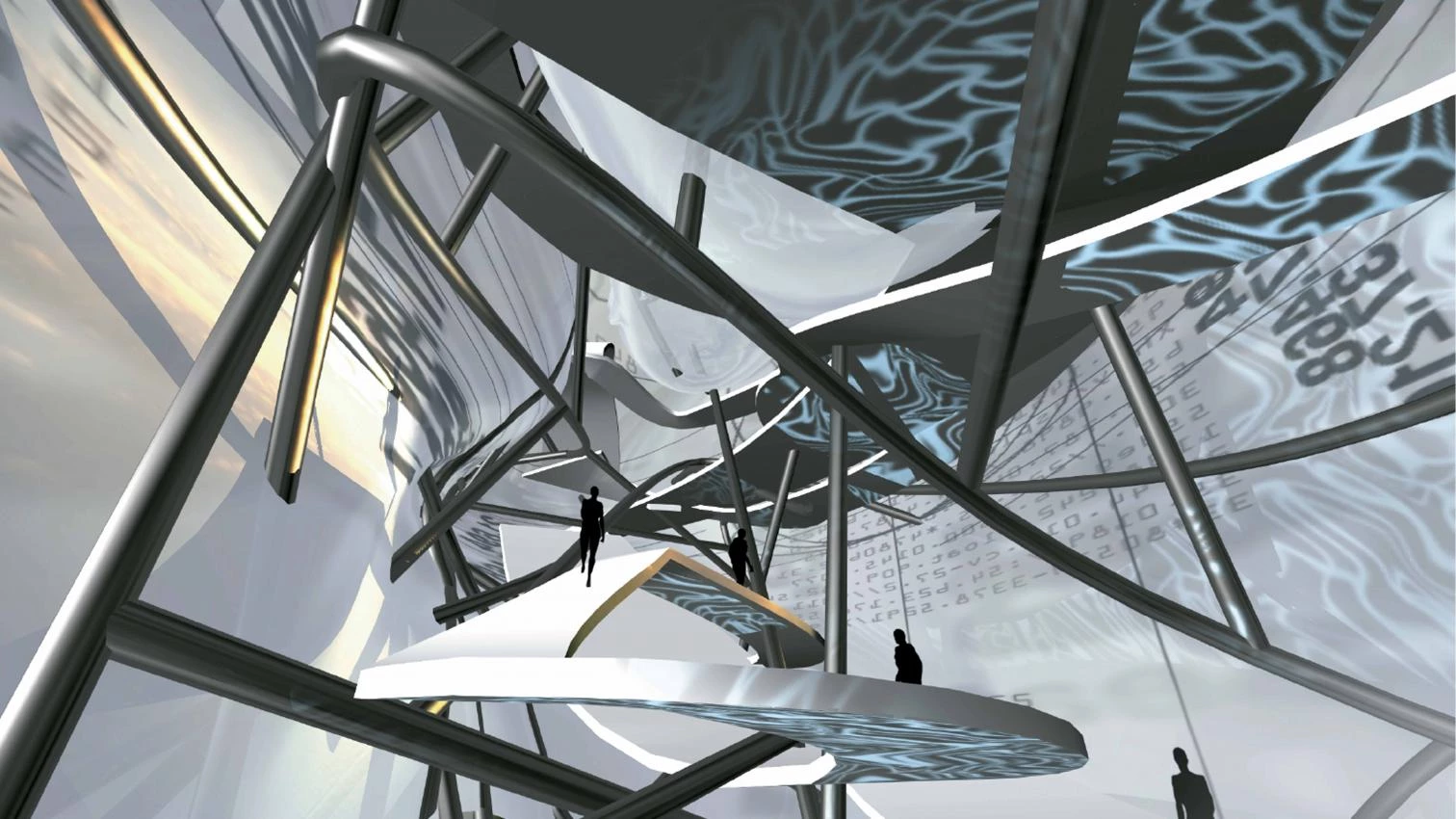

The leader of the wise fools, the brilliant and unpredictable Koolhaas, has put his talent as scriptwriter at the service of Edgar Bronfman, the heir to the drinks empire Seagram, who acquired Universal Studios and decided to emulate his aunt Phyllis Lambert´s patronage of Mies van der Rohe. As in the cases of Disney, Time Warner and Paramount, the giants of communication put together film production, television channels and theme parks to benefit from the synergy created by their symbiotic relationships. It is difficult to know how to define the territory of architecture in the vast panoramas of entertaiment, but there is no doubt that the genius of Koolhaas will be able to find, within the Hollywood dream factory, the virtual universe that the inflexible physical reality does not always allow. The DreamWorks army of animators have created in Antz a Piranesian anthill, midway between Fritz Lang and Gaudí, that supplies an allegorical image for the congestion, scale and density which the Dutch are now exploring; and it is possible that the hyperbolical future of the capitalist supermodernity will be found precisely in this architectures of digital leisure.