Building Games

The Dutch team MVRDV proposes to renew residential construction with the elementary forms used in industrial sheds or military barracks.

Monopoly is a a construction game, but a real estate game. The winner is whoever man- ages to put houses and hotels in the city’s best areas, bankrupting the other players with his greedy tolls. The colorful wooden prisms, cylinders, pyramids and arches of old building sets – similar in concept to the mythical Froebel blocks that were part of the childhood of so many modern masters, from Wright onward – introduced children to geometric order and static balance. In contrast, Monopoly’s houses and dice train the young in investment strategies and risks, providing a more dynamic, realistic and cynical model of the contemporary city, a territory governed by money and chance. Contrary to the defiant and symbolic vertical constructions of tradi-tional building sets, the horizontal landscape of real estate games represents the urbanism of economic forces and compulsive consumerism, a world where ruin is not the physical tumbling down of ambitiously piled up pieces, but the financial collapse of erroneously acquired buildings, and a competitive struggle which could be described by the blunt phrase one can read in American car stickers: “he who dies with the most toys wins.”

In spite of their friendly and archetypal image, the Hageneiland houses by MVRDV in The Hague (below) respond to the same industrial logic as the barrack huts of the reclusion camp of Guantanamo (right).

From the air, the Hageneiland development looks like a Monopoly board, with its modular houses of lively colors placed on the repeated squares of a regular site, manifesting the mix of chance and purpose that characterizes the game. Built on the site of an old airfield near The Hague, which explains its exact geometry and horizontality, a feature in any case frequent in the artificial landscapes of a country of polders, this residential islet is reserved for pedestrians, consigning parking to the perimeter. The dwellings come in one-, two-, up to eight-unit pieces that are arranged with homogeneous irregularity on four bands of uniform width, forming a tidy, dream village. The rigorous repeti-tion of a structural system – concrete gable endsand party walls combined with normalized frames and facades – is softened by playfully mixing the materials and colors of the different claddings –brick tiles, wooden shingles, aluminum sheets and polyurethane panels – to achieve a strangely seductive complex, at once naïve and metaphysical, strict and stochastic, friendly and archetypal like a child’s drawing, but also capricious like the fortuitous camp of a fairy tale king.

In the Silodam housing block, built on an Amsterdam wharf, both the typological complexity and the formal variety are a result of the apparently haphazard combination of simple elements.

One of five finalists for the Mies van der Rohe European Award, this work of the Rotterdam studio MVRDV (Winy Maas, Jacob van Rijs and Nathalie de Vries) is part of the experimental journey of a young team that in little over ten years has produced a wealth of memorable projects, from the warped sections of the VPRO television station to the over-hanging drawers of the Wozoco apartments and the surreal superposition of landscapes in the Dutch pavilion of the Hannover Expo, all based on a capacity to create complexity with simple elements that are mixed and grouped in casual combinations or labyrinthian interlockings; a procedure that comes as much from the Dalinian paranoiac critical method of their mentor, Rem Koolhaas, as from the anthropological experiments, in the fifties, of Aldo van Eyck or Alison and Peter Smithson, who along the lines of Huizinga’s homo ludens tried to make architecture a serious game. The same combination of precision and delirium is present in another recent residential project of the team, a block named Silodam – recently completed on an industrial wharf of Amsterdam – that groups an amazing variety of apartments in a colossal monolith, the prismatic rigor of which is decked with an unexpected collage of facade types, fenestration rhythms, materials, colors and textures which result in a unique patchwork that refers as much to the picturesqueness of the traditional Dutch city as to the surrealist game of exquisite corpses.

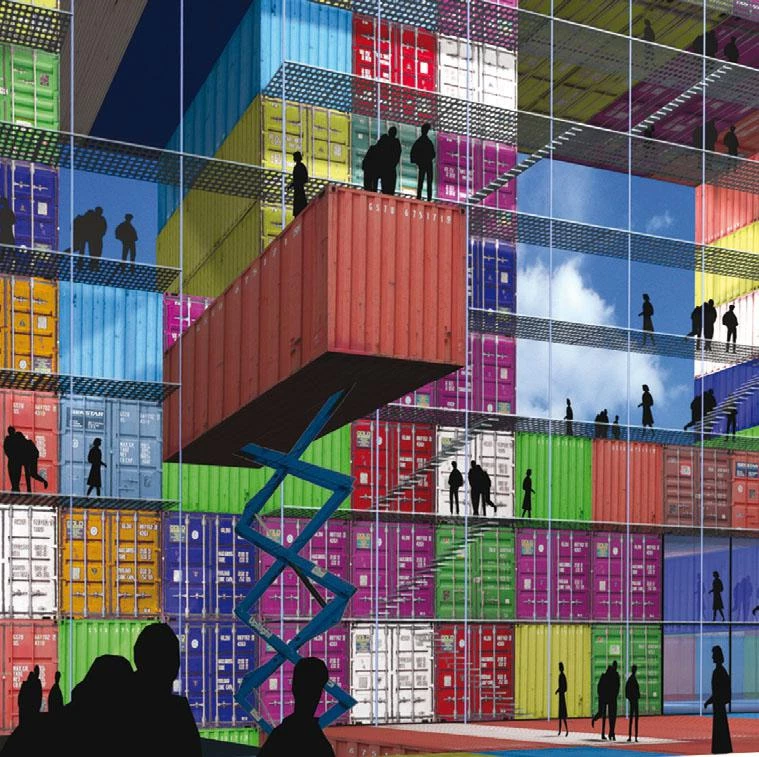

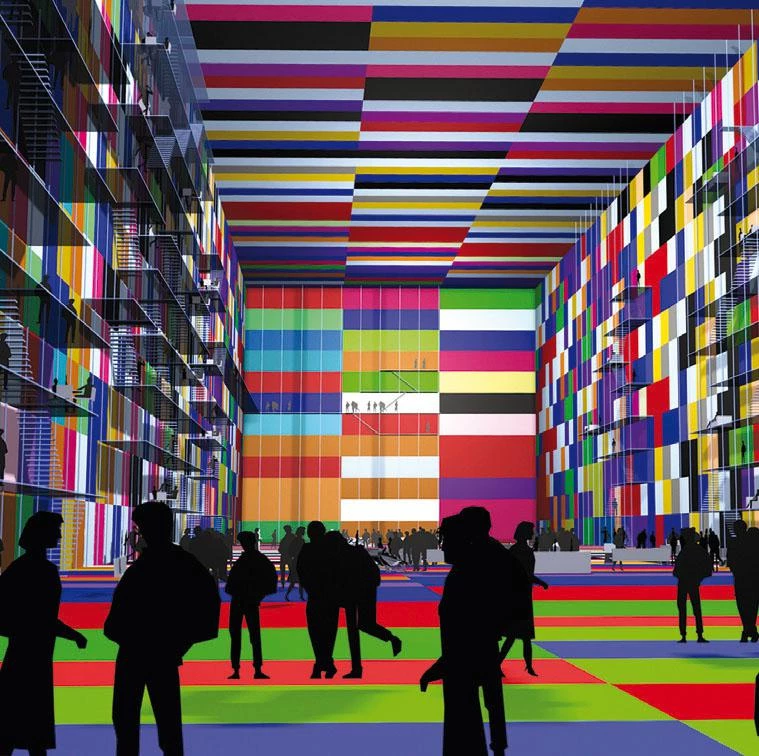

Container City

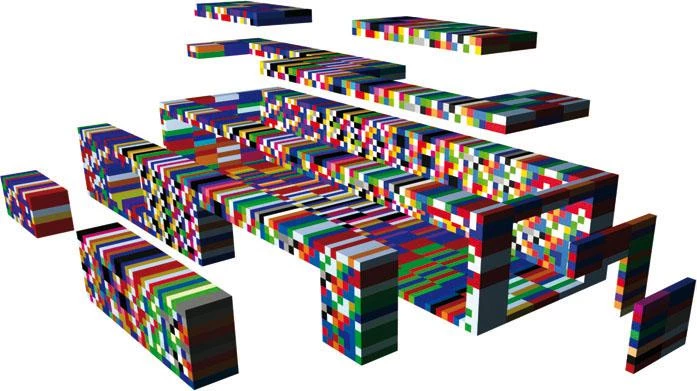

MVRDV’s hallucinatory rationalism reaches a provisional paroxysm with its Container City project for Rotterdam’s Biennial of Architecture, a piling up of mysteriously weightless containers that in their candidly chromatic schematism reinterpret with videogame futurism and kindergarten aesthetic the old modern obsessions about the industrial normalization of architecture. But this gaiety that tries to alleviate the oppressing anomy of contemporary urbanity is a product of the same sweetened infantilization of Disney or Las Vegas, in contrast to the genuine container cities that proliferate in the agglomerations of the Third World and the peripheries of the First: scenes of survival where characters as destitute and upright as Aki Kaurismäki’s ‘man without a past’ protect their dignity between walls of metal sheet; or precincts of reclusion like Guantanamo’s Camp Delta, built with standard steel containers by Indian and Filipino laborers at the service of Halliburton (U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney’s old company), and where Taliban captured in the Afghanistan campaign remain caught in the legal limbo of an American army base whose rigorous material order conceals the scandalous juridical disorder of its persistence.

Container City is an installation carried out for Rotterdam’s Biennial of Architecture around the modern obsession with serial production, and that finds its reverse in the real container cities springing up on urban peripheries.

For any architect, the extreme logic of military constructions – just like the disciplined functionalism of industrial structures or engineering works –possesses the bittersweet lure of need, and ends upbeing as hypnotic as the fierce perfection of war machines. These antebellum days, the media are with undisguised admiration transmitting to us the formidable logistics of a titanic expeditionary army. The screens and newspapers show us instant cities springing up: the canvas-lined balloon-frame camps in Kuwait, the prefabricated wooden barracks in Spain’s Rota base, and the large hospital tents or elaborate command tents that have, with their textile efficiency, replaced the roulottes bristling with antennae of the last Gulf War. The ominous, choreographic spectacle of a moving military city hits us with the formal violence of the shed and container dwellings of the toylike cities by the young Dutch architects, but this fascination becomes discouragement when events lead toward a fatal denouement and we cross the ides of March with the terrible conviction that construction games were but a prelude to war games.

In these days we have also learned that Daniel Libeskind – symbolic traumatologist of the West in the wake of the success of his Jewish Museum in Berlin – will be reconstructing New York’s World Trade Center with a commercial and elegiac project superficially decorated with diagonals and fractures, and we have seen with dismay how even on the emblematic site of modern terror – the sources of which the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk has found in the toxic gas of the First World War –, architectural games are in the end mere real estate games. While the Ground Zero of Manhattan’s Babel has failed to preserve its heart as a memorial of trembling air, Baghdad’s Babylon waits for the ire of the empire to unleash a torment of fire over future grounds zero where terror will continue to brew.