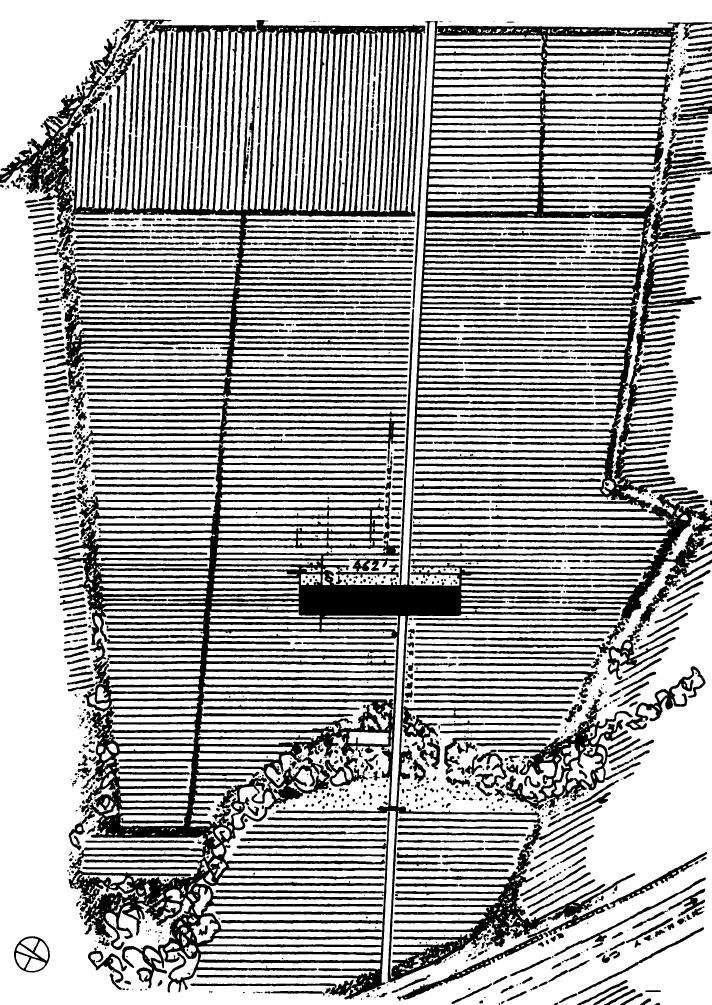

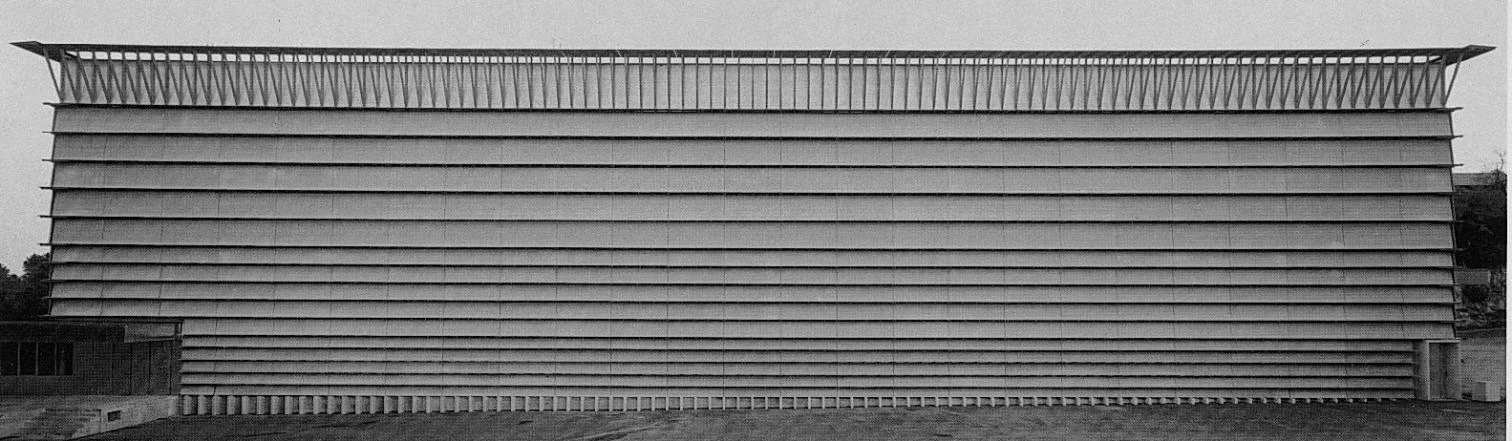

Placed in the center of the agricultural plot like a piece of land art, the prism of the winery stretches its 130 meters in parallel with the rows of vine stocks.

The mythic Pétrus de Pomerol is one of the great wines of Bordeaux. A decade ago, its producers – the Moueix family – launched the adventure of setting up a sister plant in Northern California. Under the name Dominus, Christian Moueix and his wife Cherise Chen concocted a wine that acquired instant fame, and soon had to build a winery among their vineyards in the Napa Valley, near San Francisco. As collectors of art, the couple wanted something more than a mere agricultural shed, and set out to find an architect at a par with their product. An intense search led them to Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, Basel-based professionals with impeccable artistic credentials as well as certified enophiles.

Jacques Herzog, who professes to surpass our own Rafael Moneo’s connoisseurship, assured Christian Moueix that he would try to make a building “as good as his wine,” and now, three years later, this has been achieved. Indeed, the interminable box of basalt stone that will shelter the first vintage this autumn has the refined naturalness, body and texture of an excellent wine: Pétrus has turned to stone in the Napa Valley.

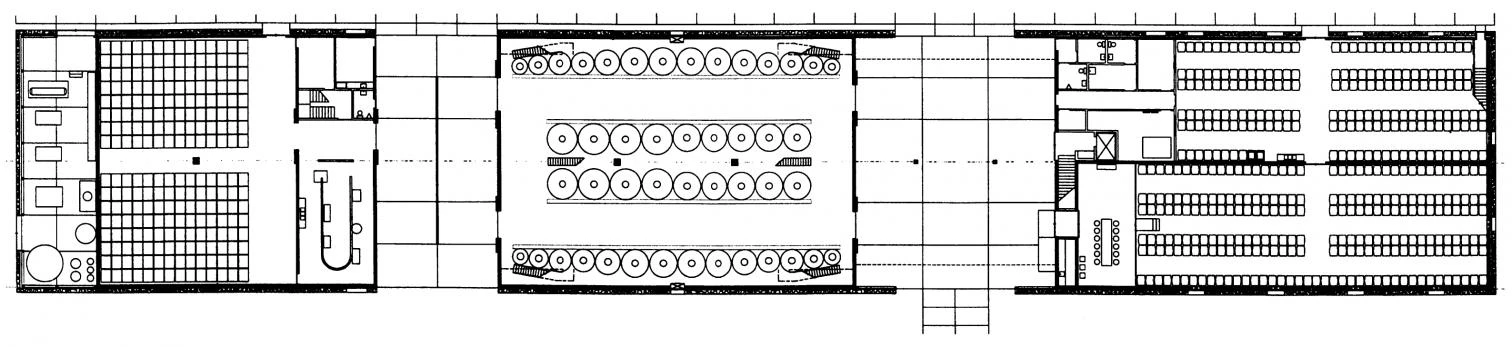

Like a piece of land art, the prism stretches its 130 meters parallel to the rows of wine stocks inside. Perforated by two large hallways, the volume is divided into three sections accommodating the metallic fermentation casks, the oak barrels where the wine ages, and a storage for the bottled produce: the standard program for any vinicultural enterprise. But here the usual functional organization is given a rare skin: large metal cages filled with dark green basalt. These geometric gabions act as brutally delicate lattice frames which filter sunlight and modulate temperature by day, while gleaming softly like geological and magical lanterns by night. The imposing facade regulates its permeability through the use of different sized stones, and the building plants itself on the landscape with Cartesian precision and mineral aplomb.

The functional and predictable distribution is clad in an unusual skin: large metal cages filled with different sized, dark green basalt stones, which filter the light and modulate the temperature of the rooms inside.

Light in the geometries forming wire baskets through space, and gravid in the tactile presence of the basalt rocks, the Dominus winery is at once contemporary and archaic. One inevitably seeks its artistic lineage in Donald Judd’s self-withdrawn boxes, Robert Smithson’s unpredictable still lifes or Richard Long’s petrous sculptures; but its categorical shape and elegant wrapping also speak of timeless construction: the uneven bond of rural sheds, the shady hallways of large plantations or the demure lattice works of southern architecture. Herzog and De Meuron were assistants of Beuys and disciples of Rossi, and such a double filiation impregnates their work with a conceptual radicality and an austere laconism that effortlessly merge tradition and novelty in an amalgam of sensuality and rigor. Their architecture is said to be minimalist and ornamented; in the Napa Valley, the minimalism becomes tectonic, and the ornamentation takes the povera form of wire netting and basalt stone.

Violent Materiality

In the Dominus winery, Herzog & De Meuron (both born in 1950 in Basel, where they set up a joint practice in 1977) have brilliantly crystallized an obsession with material, geometry and nature that was already present in some of their earlier works, such as the stone house in Tavole of 1982 and the Ricola warehouse of 1986. In the Tavole house, situated amid old olive groves and vineyards in Italy’s Liguria region, a rigorously defined concrete structure is made to contrast with the masonry of calcareous stone slabs, domesticating the tactile sensuality of the petrous bond through the intellectual rigidity of a stringent geometry, in a visual oxymoron producing both pain and pleasure. As for the Ricola warehouse, built for the sweet manufacturer in a former limestone quarry of the small Swiss town of Laufen, it confronts raw walls of rock with the stratified regularity of horizontal slats, evoking the piles of planks of nearby sawmills and conveying the same mix of constructional order and natural disorder, ultimately tapping our senses with its fascinating and violent materiality.

Herzog & De Meuron have crystallized in California an obsession with matter, geometry and nature already present in earlier works like the house in Tavole or the warehouse for Ricola in Laufen.

Jacques Herzog may be right when he declares that his buildings “are so artistic because they are so architectural.” Currently busy building London’s new Tate Gallery and recent finalists in the competition for the extension of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Swiss partners have had plenty of experience in the world of art, ranging from collaborations with artists like Rémy Zaugg to buildings for galleries, private collections and studios. Nevertheless their work remains markedly architectural in its utilitarian pragmatism and constructional feasibility. Though we can relate their projects to artists like Gerhard Richter, Thomas Ruff or Dan Graham, the architecture of Herzog & De Meuron will not cease to be the social sculpture that their master Beuys wanted and the public art that their teacher Rossi advocated. And if we overemphasize the cosmetic dimension of their exquisite skins, we will hardly be doing justice to the «hidden structure of nature» that their buildings reveal through the surface, turning into visible pleasure the invisible emotion of the work.

In those steel gabions that serve to discipline the basalt the way metal meshes stabilize the slope of a mountain, there is the same kind of mysterious wisdom that permeates the flavor or aroma of vintage wine: familiar yet strange, at once predictable and disconcerting, a product of both experience and chance just like any human creation.