Jacques Herzog

For a young architect at the beginning of his career it is a challenging moment to see the widely admired work of established colleagues, often with a mixture of disdain and admiration. For my generation this moment was in the 1980s, a period which celebrated the peaks of postmodernism. Luis Fernández-Galiano’s Fracturas y ficciones reads like a diary of that period before it was driven out by new trends, such as minimalism and a leaning towards the iconic.

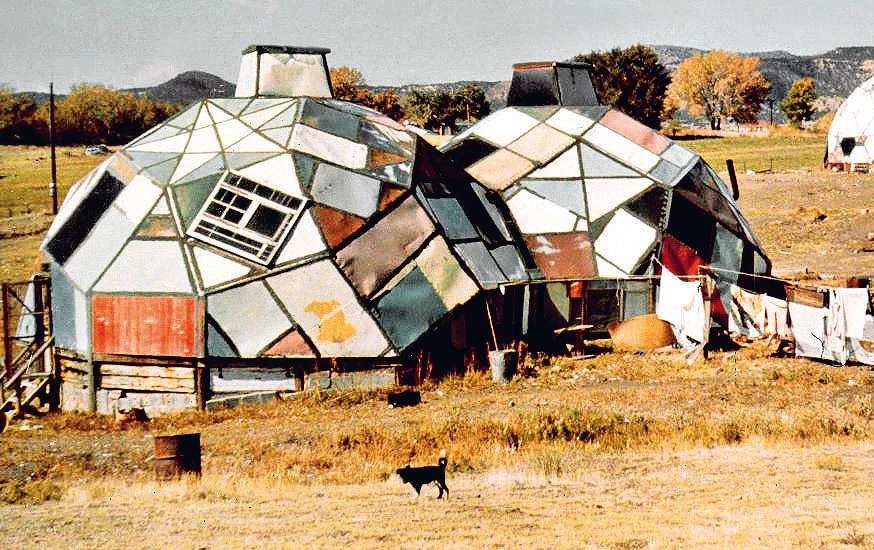

In Empeños sostenibles, the first one of Fernández-Galiano’s impressive double volume Las grandes esperanzas, the author presents texts and essays that he wrote in the years between 1976 and 1984. They are fresh and read as if they were written today. We learn how closely energy and architecture have been related from the early days of firemaking to the current problems of shrinking resources. Luis Fernández-Galiano started at the young age of 26 to write these texts which later culminated in his doctoral thesis, El fuego y la memoria. Thus they paved his way as a writer, critic, professor, and public intellectual. His alert and witty writing has enabled him, until the present day, to reach also politicians and opinion leaders, beyond the field of architecture.

Miguel Aguiló

In the two volumes of Grandes esperanzas, Luis Fernández-Galiano reflects on what happened in Spain during the most exciting period of its recent history. In theory these are ‘architectural texts,’ but they are broad in scope, as is usual in an author who, ever attentive to the stamp of context, makes his writings indispensable aids in understanding the history of this country. The first tome, titled Empeños sostenibles, tackles the technical preoccupations and perplexities regarding topics like construction, energy, and sustainability in a nation shaken by political events, mixed with the oil crisis and its economic consequences.

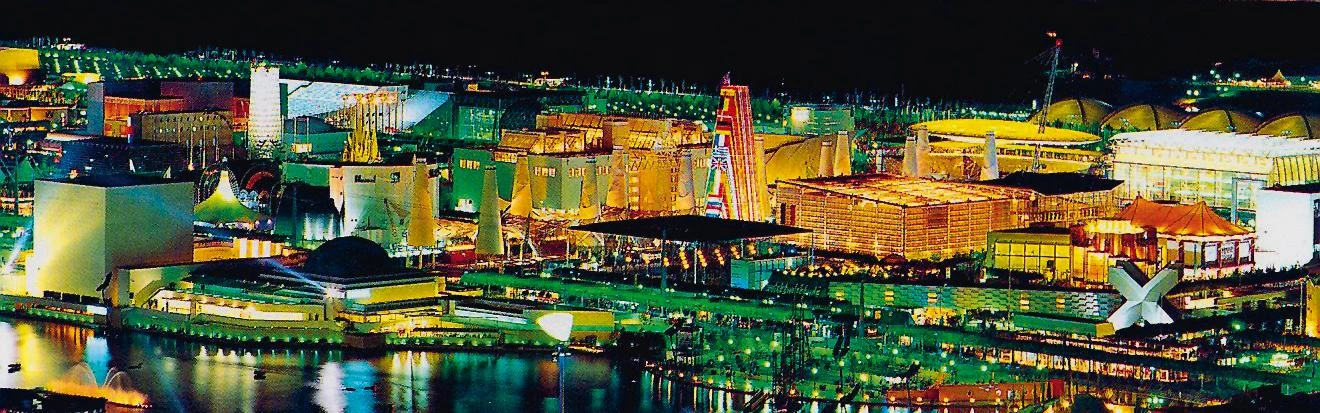

The second, Fracturas y ficciones, addresses the combination of questions surrounding architecture, history, and art that crop up in a society boosted by its presence in Europe and busy preparing for two different celebrations at the same time. Organized by themes, the twenty-four essays of the former have the format of magazine articles, whereas the hundred pieces of the latter are brief and sundry portraits, so the reflective and prophetic tone of Empeños sostenibles complements the fleeting diversity of Fracturas y ficciones, engrossing the reader. Two books to keep within reach.

If the 1970s focused on the vernacular and the alternative, the 1980s witnessed the heyday of postmodern classicism and the emergence of deconstructivism, in coincidence with the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Norman Foster

Luis Fernández-Galiano’s two volumes of writings spanning the period 1976-1992, with the title Las grandes esperanzas, embrace architecture, urbanism, technology, history and art with an insightful blurring of the edges between these subjects, and always with a contemporary relevance. As a scholarly and thoughtful critic, he opens up our mind and our eyes. In the latter case quite literally because, like an art director, he skilfully matches images which are as visually provocative as the text – a uniquely stimulating combination.

Rafael Moneo

A publication of this kind shows how articles originally written to cover and critically interpret goings-on in architecture can in the course of time and in a new form, that of a book, become a bona fide chronicle of what happened: history. It has no need for structure, as continuity and order are established by the actual chronology of events, and shape the books page after page. It is as if the author, in his determination to objectify all that came to pass, wishes the facts to speak for themselves when positioned in the political and cultural horizon that they took place in, and he is the conscientious notary in charge of documenting them.

Carlos Jiménez

The all-embracing rubric of Las grandes esperanzas takes us through seventeen years of writings by the persistently prescient architect and critic Luis Fernández-Galiano. A remarkable two-volume set that under its distinct pairing reveals its author probing a future that was to become our incontrovertible present. One of the many delights of this perspicacious compilation is to follow Fernández-Galiano’s inquisitive, lyrical mind in full motion, either foretelling a local euphoria here, an optimistic surge there, or a global crisis ahead, all delivered in a syntax that elevates the travails of journalism to literary achievement.

Sublimating the turmoil and aspirations of two decades in tow, we arrive at the end to an expectant 1992. A momentous year indeed, one that also serves as prelude to Años alejandrinos, Fernández-Galiano’s equally impressive collection of ensuing writings. After reading Las grandes esperanzas, the year 1992 felt like the celebration was over before it had begun. But the writings remain, and others will have to be written, for as Aldo Rossi reminds us: “There is nothing left to do but to resume, with persistence, the reconstruction of elements and instruments in expectation of another holiday.”

The narrative of the book stretches on until the annus mirabilis of Spain, which in Madrid, European Capital of Culture, opened the Thyssen Museum, and on Seville’s Cartuja Island raised the Expo pavilions.

Renzo Piano

These texts by Luis Fernández-Galiano from the 70s and 80s prove that the big shifts in the world are visible to those that have eyes to see well before everyone else. It was like that for me: I was so absorbed in those years by my work that I did not recognize (except, maybe, for my instinctive attraction to light and lightness) the environmental revolution at its beginning.

However, since then, slowly (too slowly), I became aware, and we all did, of the necessity to design more sustainable buildings. Luckily, necessity (the pure force of necessity), is the safest source of inspiration and the strongest antidote against academia. This is why I now feel better, because building a wiser world is not just an obligation, but also the best opportunity to explore a new poetry in the language of architecture.

Dominique Perrault

Architecture physically underpins and shelters lifestyles, economic stability and political visions. In this sense, the wonderful compilation of essays and articles of Luis Fernandez-Galiano forms an exciting and passionate critical review on architecture, in its relationship with history, economy, art and society, over a fertile and turbulent period from the end of the seventies to the beginning of the nineties. Over three decades later, we inherit many of the concerns already emerging at that time: the emergence and awareness of ecology and climate change, the need to build sustainable cities and architectures, the concerns about the impacts of technological innovations, and so on.

Today, at a time of deep crisis linked to the Covid-19 pandemic, this book carries a very special echo. Architects will pursue the debate. They will have to grasp the urgency of our situation, to respond with determination by reinventing the way we build our cities and buildings, according to new ways of working, communicating and moving. With a conscious and critical look at the past, I believe in the ability of architects and urban planners to build bridges and to imagine the future in a pragmatic and positive way. These ‘Grandes esperanzas’ are needed now more than ever.

Eduardo Souto de Moura

No, Las grandes esperanzas is not a book, but a collection of timely records, fragments without doctrine – because it is not a religion; it is no longer about the ‘Death of God’ or the ‘Death of Man,’ but about the death of the world, which we are obliged to prevent, for the sake of survival.

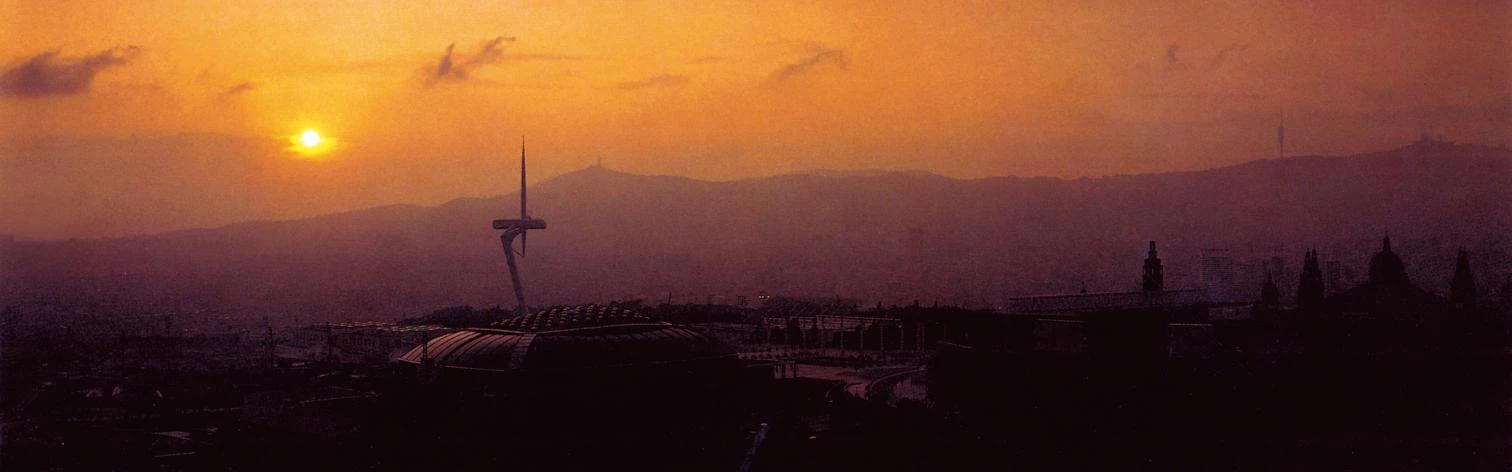

In 1992 Barcelona’s hosting of the Olympic Games served to revamp the city, which has since been looked up to as a model for many others, but the country’s magical year closed with the bitter taste of economic crisis.

José Manuel Sánchez Ron

Architecture is a displicine that is so plural and so rounded – covering technique, science, art, and society all at once – that it can be regarded from very different perspectives. The articles that Luis Fernández-Galiano has brought together in two gorgeous volumes possess the great virtue of uniting all of those perspectives, showing the harmony that throughout a large part of the 20th century underlay architectural development and sociopolitical history, especially but not exclusively, in Spain. It was definitely a time full of hope, and a time that bore fruits.

Fulvio Irace

In 1955 Bruno Zevi started publishing a magazine called Architettura. Cronache e storia, of which he served as editor for almost half a century, until the end of his life in 2000. The juxtaposition of the two terms – chronicles and history – meant for him the need to link together the fleeting glance of the critic with the long distance of history. Zevi did believe that short and long history needed a reconciliation, so that the critic would be able to work using knowledge of the past (usually a prerogative of history) and the historian could be aware of the present as a vantage point for assessing the past.

Zevi was asked by the weekly magazine L’Espresso to serve as columnist for architecture, and after a few years he started collecting his columns in an editorial series – Cronache d’architettura – that up to this day we use as a precious source.

I believe that this latest work of Luis Fernández-Galiano – architecture professor, critic, historian, and editor – can be read as an answer to the same need: it aims to blur the borders between criticism and history, brilliantly demonstrating how the ephemeral act of criticism becomes part of a broader concept of history, like single fragments composed into a grandiose fresco of several past decades.

Not by chance, one of the first essays in Fracturas y ficciones – ‘La nueva historia es vieja’ – focuses on the issue of ‘new history’ and the danger of it altering our reading of the past. Luis Fernández-Galiano’s short pieces – mapped as part of a cultural geography along thematic coordinates – clearly demonstrate the need for history to be ‘total’ (if not global), in the process using any possible strategy (architecture as art, photography, social and political issues, and so on and so forth) to explore the density and complexity of the past as part of our present.