Question: Thank you so much for receiving us in your home here in Punta Nave, near Genoa, your hometown, where you were born almost eighty years ago. You turn 80 in September, and this is perhaps a good moment to go through your biography. An asteroid was recently named after you. Only Buckminster Fuller has something like that, a molecule named after him. An asteroid is larger, 5 kilometers in diameter!

Answer: I think everybody has a star somewhere.

Q: You were telling me before that everybody needs an inner compass, as ships do, to guide them in life. I would say that your inner compasses are building on the one hand, and people on the other. Building for people. Were these your two references in youth?

A: I use the word ‘compass’ because I like the idea of boats, and I like the idea of a compass you don’t even see because it’s inside your body, and can’t be disturbed because it’s well protected against magnetic fields. ‘Compass’ refers to many things. It’s not built-in, but self-built, something you build yourself, from childhood and teenhood, through experience.

Q: You started to build this inner compass in childhood? What kind of a childhood did you have? Your father was a builder.

A: A small builder, not a big builder. That makes a big difference. Big builders are business people, small builders have real ground, they are craftsmen. My father had ten or twenty people working with him and I would spend my free time with them, on the construction site, sitting on sand. When you grow up in this atmosphere, you start to build a little compass somewhere, watching how things become a building, sand becoming a column, bricks becoming walls. Pure magic to a child of 6, 7, or 8. All this stays with you. Another thing is the harbor, which is a magical city, where nothing touches ground. Ships float. Buildings levitate. And the cranes… Everything flies!

Q: But besides these influences, there’s the family. What role did your parents play? Did they want you to be an architect?

A: Well, my father was a builder so he told me I should be a builder, but it didn’t really matter, he was a very tolerant man. I told my mother that I thought I should be an architect. She said I would have to explain it to my father. So I went to him. He said, why an architect, you can be a builder. A builder is something more than an architect. My brother, ten years older, was also a builder. The truth, I didn’t really want to be an architect. I just wanted to run away from the family. That is what you want to do at 18.

Q: So you left the family in Genoa, and went to Milan.

A: And before that I went to Florence, which is beautiful, but too beautiful. And if you’re 18, 19, or 20 and learning about architecture, and you go to a place like Florence, you feel paralyzed by so much beauty and perfection. At some point I said, this is too beautiful, I have to go to a place that’s much less beautiful. I went to Milan, which was less beautiful but more interesting, socially speaking. It was the beginning of student occupation of schools. I led a double life for at least two years. During the day I worked in an atelier, with Franco Albini, which was fantastic. I was learning to be an architect, drawing and all. In the evening I was joining in the occupation activities. But all these things contribute to the making of a little compass, a treasure in life. This self-compass has different names. And it’s not just about one’s profession. It’s about life, about people, about commitment, about politics in the real sense of the word. And there’s another thing, more difficult to touch on: sense of beauty. It’s not just about people, it’s also about color and light. If you grow up by the Mediterranean, you absorb something from this water. This sea is full of light, vibration, voices, and perfumes. Somebody said that the water makes things beautiful. It’s quite true.

Q: When you say that your final home will not be in Paris or Genoa or New York, but on a boat, I can understand it, given your Mediterranean roots. But let me now ask you something about your education. Did you learn more from Albini than from the teachers in Milan? You always speak of him with great devotion.

A: I went to university really to ‘occupy,’ not to study, so yes, I learned more from Albini, but also because he was a real craftsman, someone who took pleasure in doing things, checking, controlling, making prototypes, making pieces. It was a good school, but you know, I wasn’t very good at school when I was a child, so I grew up with the idea that, by watching people, you learn. You don’t grow up with the arrogant attitude of thinking you know enough. On the contrary, you grow up with the idea that you have to learn because you’re not good enough.

In Praise of Optimism

Q: So you were like a sponge with Franco Albini.

A: Albini was one. Also, there’s a non-romantic aspect of things and events. I was born shortly before the war. I’m the child of a storm. When the war ended, I was 8 years old. So I grew up with this feeling that things would become better in time. Every day, every week, every month, the street would be a bit cleaner, my father would come home a bit more relaxed, the food on the table was better. I grew up with the idea that the passage of time improves things. It’s mad, but it gives you the optimism you need to be an architect. I grew up with this idea, and even now I think that tomorrow will be better than today.

Q: Yes, we all know that you can’t be an architect unless you’re an optimist.

A: Optimistic from every point of view, especially if your work is to make places for people, where they can come and stay together. It’s about a civic duty. Then the world is a little better each time, it is. It’s little by little, drop by drop, day by day, but you’re doing something to make a better world. If you don’t believe in the capacity of architecture to change the world, if you don’t believe in the capacity of beauty, and civic life and civic values, to make a better world – for me it’s not just utopia, but a real possibility – then you had better change profession, you’re in the wrong one…

A Place for People

Q: I want us to wrap up this conversation discussing your recent project in Santander, where you have finished the Botín Centre. That’s good news because in Spain before, you had only built a small base for Luna Rosa, in Valencia.

A: I never really worked in Spain so I’m pleased I’ve been able to do this. It’s fantastic for a number of reasons. First, I learned to love Santander, which has a double identity: one towards the Atlantic, and one on the bay. The first one is rougher, breezier, with the waves coming. The other one is like a lagoon with light which is very similar to the light of Venice. The Jardines de Pereda look south and at the bay… the light is fantastic. I saw the place after Emilio Botín came to us, and I was seduced by it… but also by the family, especially Emilio Botín. We became very close quite quickly. I never thought of him as a banker, but more as a dreamer. He was quite a tough banker, I guess, but he was also a man who was in love with education, with the new generations, with Santander… and with the idea of building something there. The Jardines de Pereda were separated from the bay by a busy road, and the decision to take the traffic down so that the Jardines could reach the water became very important. It was made with the family, with Emilio, with the mayor, and of course with the community. So it was, again, a story of love for public space. It was not about rhetoric or about showing muscles. Emilio Botín wanted something with a presence, but without standing out too much in the place. And that’s why we made the building fly… because we have the trees there, so when you come from the city, you go through the park, so by putting the building on columns, like trunks, the building actually disappears. You see through the leaves, the ground floor is free. If it rains you go there and you’re in the shade if it’s a sunny day. Then you go up to the Plaza, a kind of space between the two buildings.

Q: You imagine it full of people moving up and down…

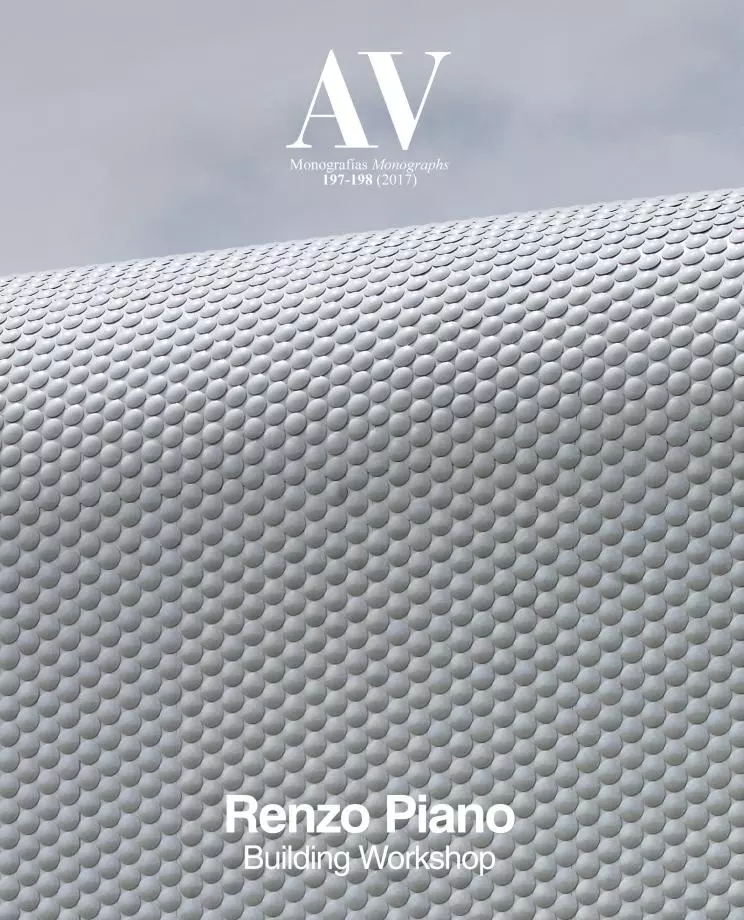

A: As soon as it stops raining in Santander, everybody goes to the Paseo. This building is right at the end of the Paseo, where it joins the Jardines… so of course people will be a sort of fourth dimension. There are not just three dimensions, there’s a fourth one: movement. This is also true at the Pompidou, with the escalators. It’s about movement. Even the Whitney, with those stairs. It’s about people moving. What I expect from Santander, from the Botín Centre, is that the ground floor, the plaza, and the stairs will be full of people moving, resting in the bar or just sitting… This will also be very good in the summer because we’re in the shade. And the magical thing there is the light. When you look southward, the light touches the water and rises. The skin of ceramic pieces, 270,000 pieces of nacre, mother-of-pearl, reflects the weather, the light. So it’s a bit organic, like a fish jumping out of the water.

Q: With shiny scales…

A: There’s a reason for this. We wanted the building sparkling and playing with the light, gray light or sunny light. Even in the rain. We wanted a building that would have a kind of sparkling skin. So I cross my fingers. I think it’s going to be loved… A good building is one that’s loved, adopted by people. A place like this is what makes cities good places to stay in, because it’s about tolerance, sharing, values, enjoyment, community. This is important. The greatest joy of architects is to see their buildings loved by people. So, whether in Rome or New York or Paris or San Francisco, if I see people smiling and enjoying my building, it’s a joy.

Q: That’s a good way to end this conversation about the points of the inner compass that has guided you since childhood. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince has an asteroid, as you do, so now you can join the little prince up in the stars…

A: When they called me about this, you know, I asked if this was a safe asteroid. They said, of course, we’ve been checking for ten years, don’t worry. For how long, I asked. They said, for at least two million years, the asteroid is safe!