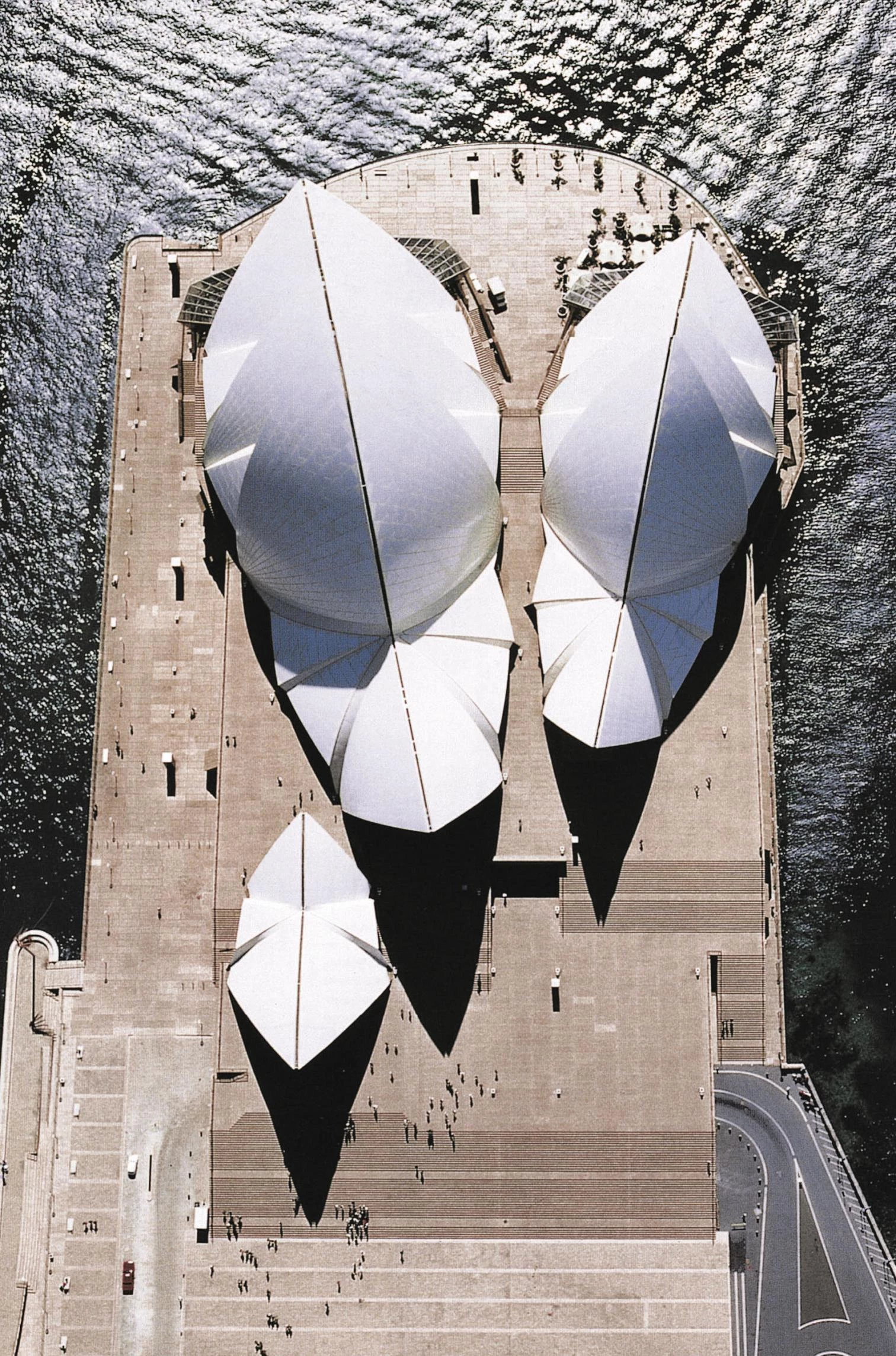

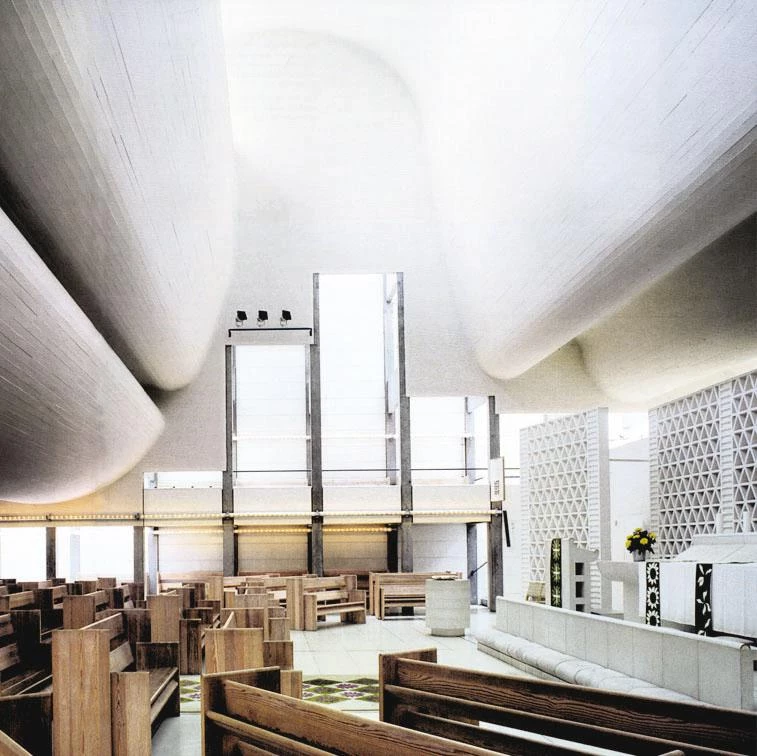

To celebrate its 25th anniversary, the Pritzk-er Prize goes to a great Dane who a quarter-century ago had already made history. In 1978 Jørn Utzon received the Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects – a prestigious centenarian award that this year falls upon Rafael Moneo –and by then his creative life was substantially completed. Five years before, the wind-filled crustacean shells of the Sydney Opera had begun a bittersweet sail after a long process full of discrepancies that in 1966 had finally drawn the architect away from the country and the work; and while an already Australian symbol opened without its author, Utzon designed what was to be his last capolavoro, the church of Bagsvaerd, an exquisite cloistral shed with sheet roofs and undulating ceilings of concrete outside his native Copenhagen, which on comple-tion in 1976 wrapped up a career marked by a fas-cinating formal inventiveness.

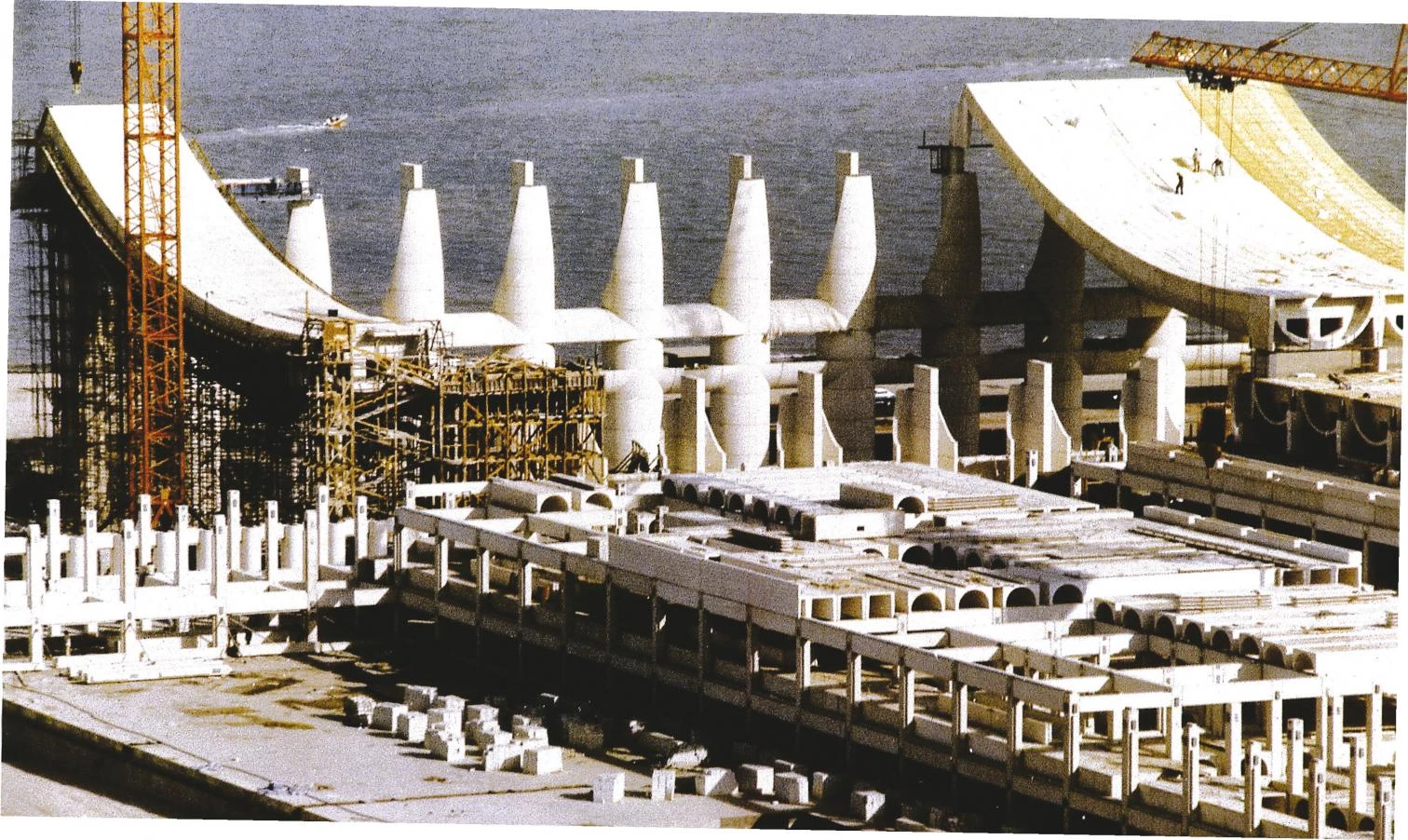

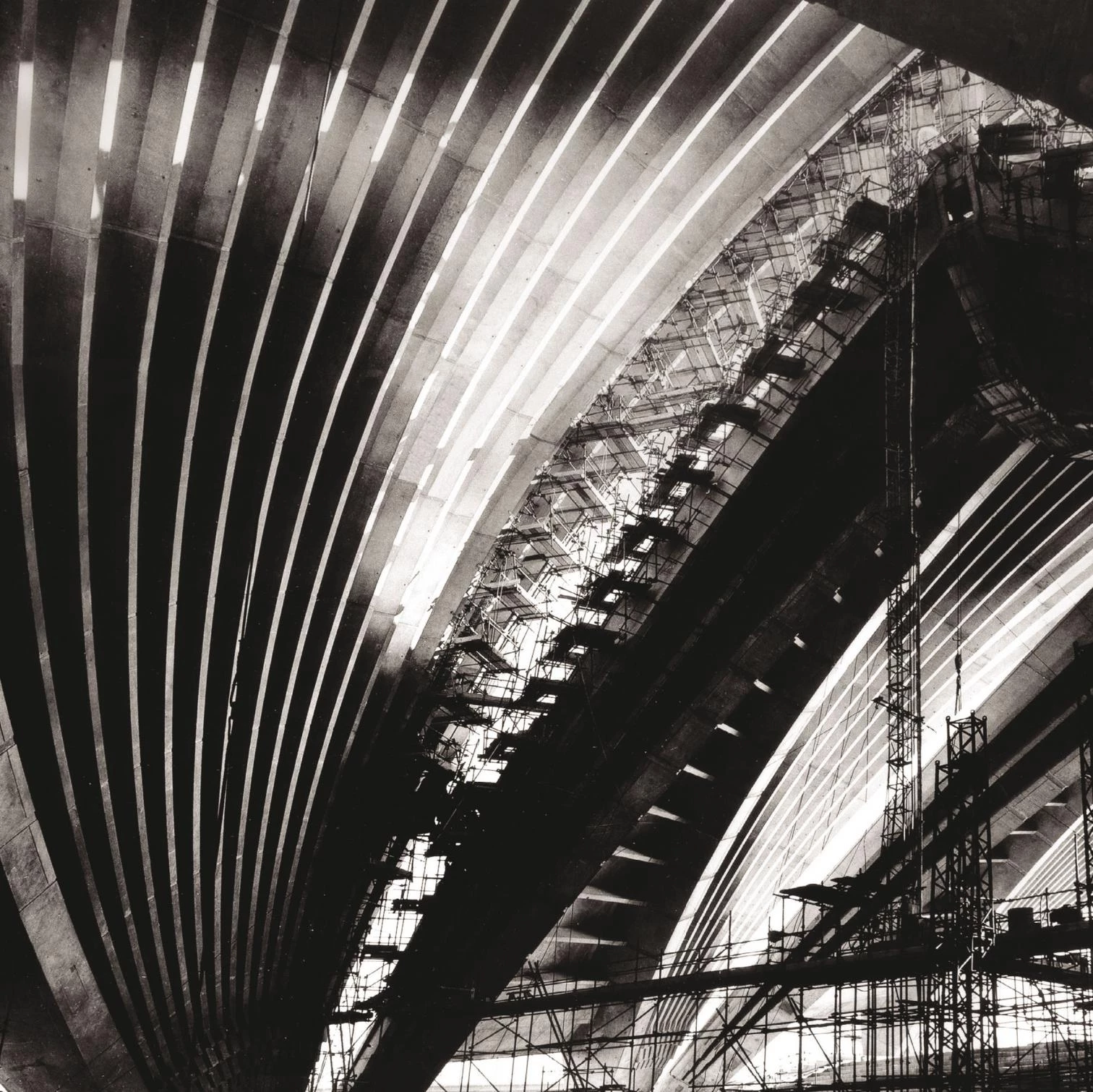

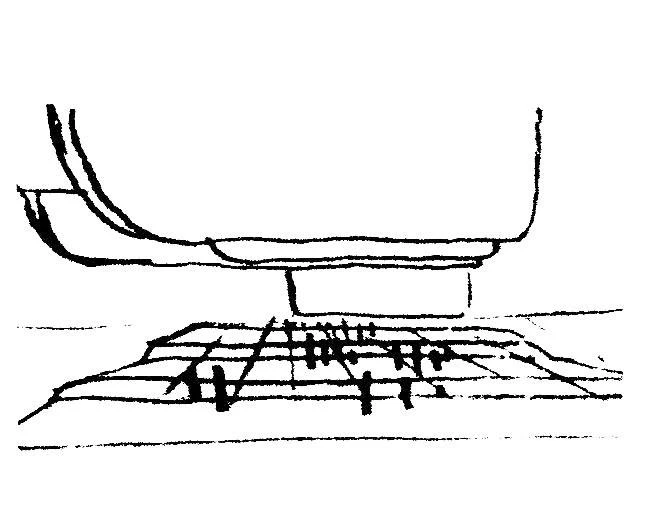

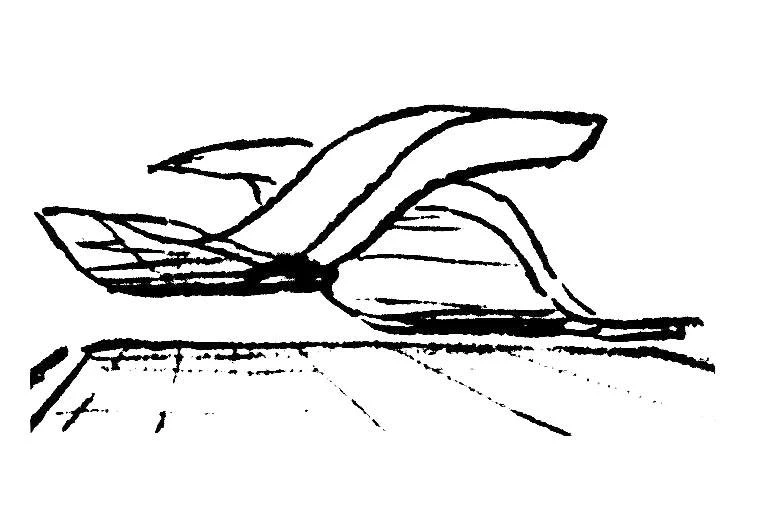

Turned into symbol of a whole continent, the Sydney Opera House is an extraordinary aesthetic achievement, but also the result of a colossal effort to integrate all the technical and formal aspects of the building.

Behind was the vernacular topography of the Kingo Houses, with the landscaping intelligence of their courtyards arranged in sequences and the tac-tile sensibility of their brick masonry, designed shortly before the Opera House competition that in 1957 gave Utzon the equivocal prize of fame, and extended soon after in another model residential development, the Fredensborg complex. Behind, too, was the unique project of a museum for the artist Asger Jorn, a cluster of jars or buried coconuts tan-gled in ramps that joins the Einsteinturm and the New York Guggenheim to Kiesler and Ronchamp. Behind was his first Mallorca house, a severe and archaic work of stone, geometry and light where he would become a recluse in 1973. And behind was, finally, Kuwait’s National Assembly, a labyrinthian bazaar in penumbra with solemn arcades made of concrete canopies, echoing Chandigarh, whose monumental architrave prefabrication took ages to complete, only to be downed in the Gulf War and reconstructed with less fortune later.

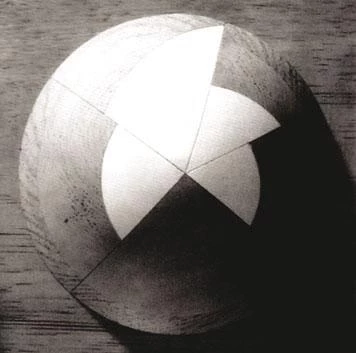

The shells of the two auditoriums were designed as fragments of the same sphere.

When Utzon became an honorary and secret Majorcan, the Scandinavian architect was already recognized as one of the great masters of the century: a disciple of the Aalto whose traces were everywhere in his work, from the fans of the Birkehøj houses to the waves of Bagsvaerd, but also an independent talent who engaged in dialogue as much with the late work of Wright and Le Corbusier as with the contemporary projects of Kahn, Tange or Niemeyer; a laconic humanist who reconciled tectonic industrialization to preindustrial archetypes, and the construction with elements of modernity to the timeless eloquence of anonymous or historic architectures learned in his travels; and an innovator of form who materialized the lyrical essence of his architectural research in feats like the platform crowned by a canopy of light roofs.

Since then, this strayed heroe in his island refuge has been the target of numerous critical attempts to make his figure resurface. Some point him out as the expressionist, eclectic visionary who in Sydney spawned the genre of mediatic constructions of the society of spectacle, never failing to mention that the Saarinen of TWA fame was in the jury that chose the soaring Australian sails. Others have preferred to revive him by praising the organic wisdom of his residential works, emphasizing the silent elegance of his Danish developments and Majorcan houses. And a few have retraced his career from the perspective of the situationist poetics of the formless, placing the project for Jorn and the CoBrA con-nection in the core of his artistic experience.

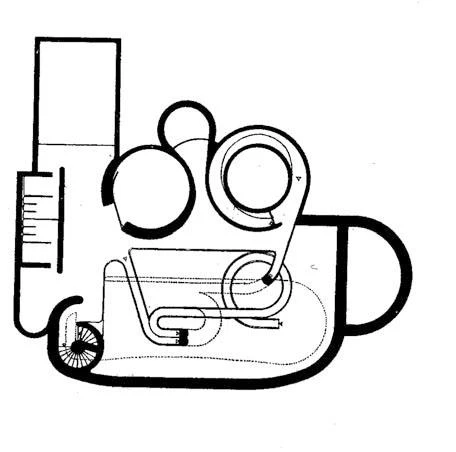

The Bagsvaerd church and the National Assembly of Kuwait (above and below) show Utzon’s masterly reinterpretation of the symbolic past; and the plan of the museum for Asger Jorn, his ties with the artistic avant-garde.

It is hard to tell which of these aspects has weighed most in the decision to give him the Pritzker, which for the second time will be awarded in Spain, the 1997 ceremony having been held in a Guggenheim-Bilbao still under construction –where the awardee, incidentally, was another Scandinavian, the Norwegian Sverre Fehn. But the au-thor of the Sydney of titanium that rises on the banks of the Nervión was in this year’s jury, and one can-not help thinking that, prior to the ecological Utzon or the Jorn-Jørn connection, it is the Australian icon that prodded the Pritzker brotherhood to celebrate its silver anniversary with this architecture of gold: a metal that fetches a high price in times of uncer-tainty, and a safe assett in times of change.