Not since a half-century ago has Europe lived a more cruel April. The human tragedy and the political drama of the Balkans transforms the symbolic body of the continent, and the silky flesh that Titian or Rubens painted astride a vigorous bull of foam becomes the pallid, ghostly skin of the woman embraced by death in Hans Baldung Grien’s disturbing canvases. The smug and opulent sensuality of the Europe of the single currency gives way to the perverse and necrophiliac eroticism of the alliance that defends life with the vulnerable beauty of an invisible airplane. Yet the world follows its course, and while the criminal pulse of an enlightened nationalism drags Serbs and Albanians toward an abyss of pain and bitterness, European leaders gather in Berlin or Brussels to discuss milk and cereals, roads claim their share of victims of leisure, and architects calmly celebrate the best projects of the season.

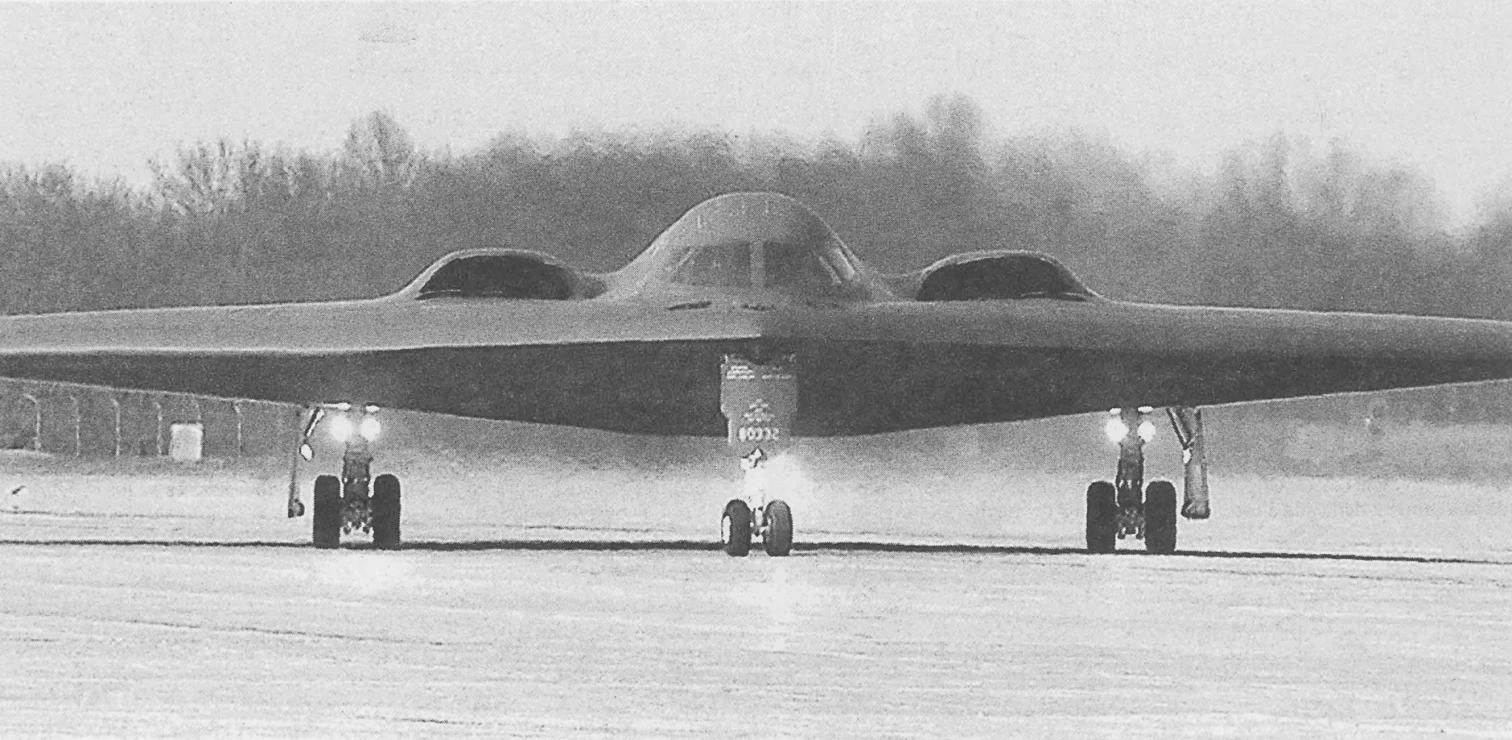

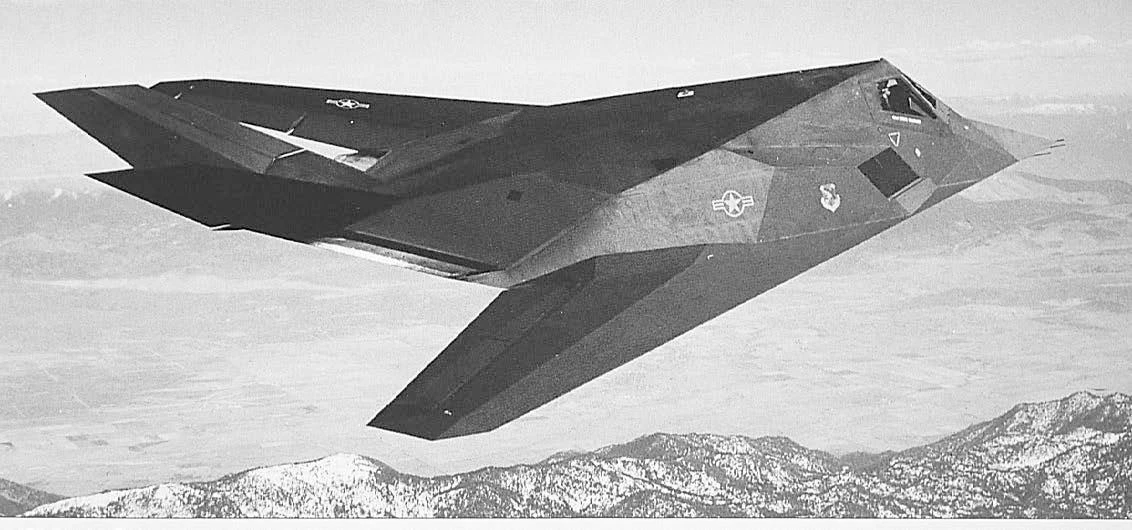

The aeronautics industry exhibited in the war of Yugoslavia the folded forms of the F-117 (below) and the sinuous profile of the B-2 (above), two planes whose fragmented or formless geometry fascinates architects.

The most popular of Europe’s prize-givers is undoubtedly the Europan, a huge competition held every two years that mobilizes armies of the continent’s young architects to draw up residential projects for the numerous European cities that offer sites and commissions, from Finland to Greece and from Portugal to Rumania. But the most prestigious prize of all is the Mies van der Rohe European Architecture Award, which is funded jointly by the European Parliament and the European Commission, and handed out also bienially – through a Barcelona foundation that has its offices in Mies’s famous pavilion there – to specific buildings carried out by European architects in countries of the European Union or associated states.

After winning the Carlsberg Foundation award, Peter Zumthor obtained the Mies van der Rohe Prize for his Kunsthaus in Bregenz, earning the highest recognition for a building constructed in Europe.

Europan announced the results of its fifth edition on the last day of March, having this time rounded up 1,700 projects for sites in 65 cities, and made 13 juries decide on a total of 50 awards and 63 honorable mentions. The Spanish case had its customarily high participation rate, and the results speak for the good health of our young architecture. For not only were all the slots disputed at home allotted a Spanish winner; young Spanish architects also reaped one victory outside of Spain. The three Madrid teams of Cano & Abarca, Eduardo Arroyo and Hevia, García de Paredes & Ruiz triumphed in the sites of Almería, Barakaldo and Cartagena, respectively, as did the Sevillian duo of Morales & González in the north African city of Ceuta, while Madrid’s Alberto Nicolau carried the day in the Dutch city of Almere, a particularly important achievement considering that Spaniards rarely venture to compete abroad – even when, as in this case, the referees are known to be hardly biased in favor of home teams.

The Convention Center in Lucerne, by Jean Nouvel, the Liner Museum in Appenzell, by Gigon & Guyer, and the villa in Bordeaux, by Rem Koolhaas all competed in the final round for the Mies van der Rohe Prize.

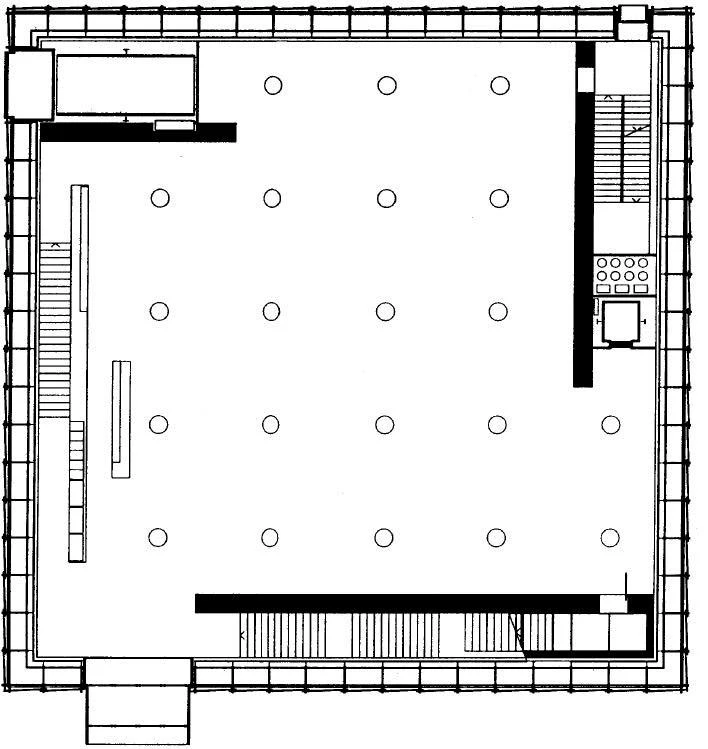

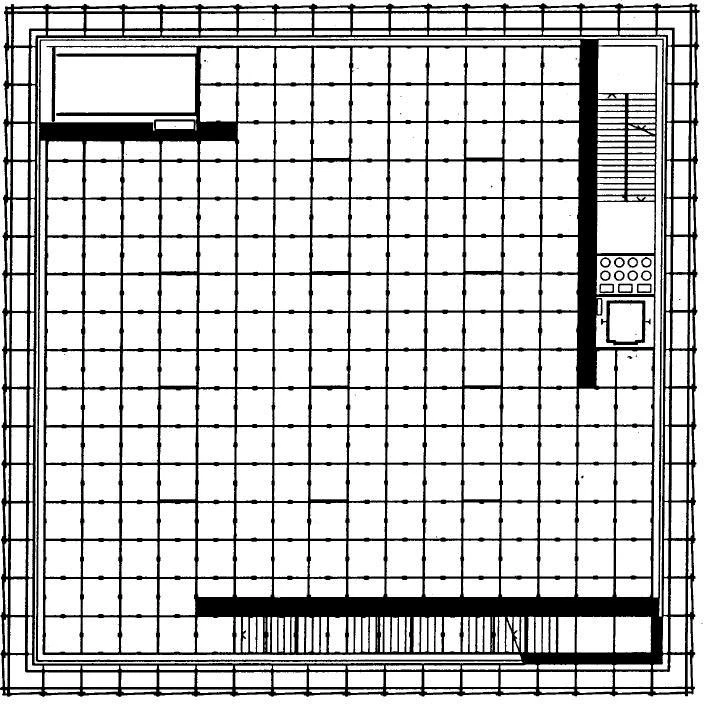

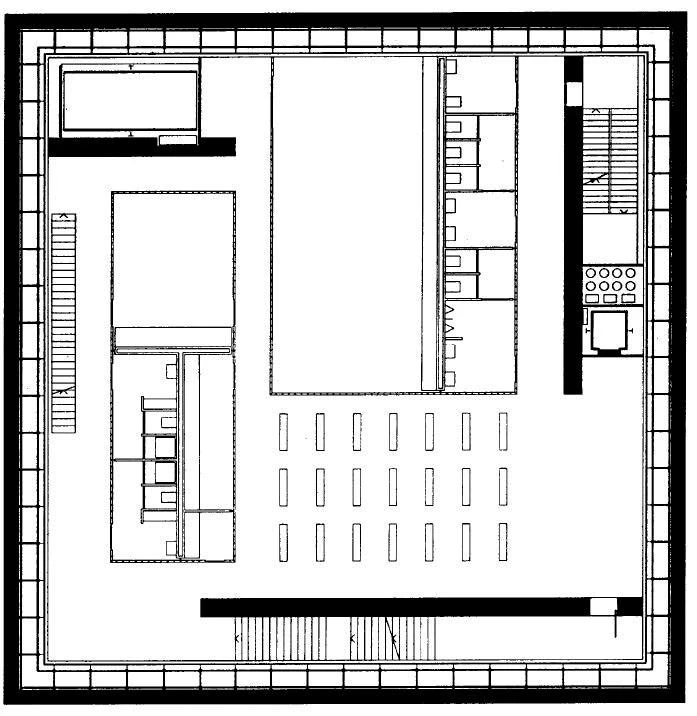

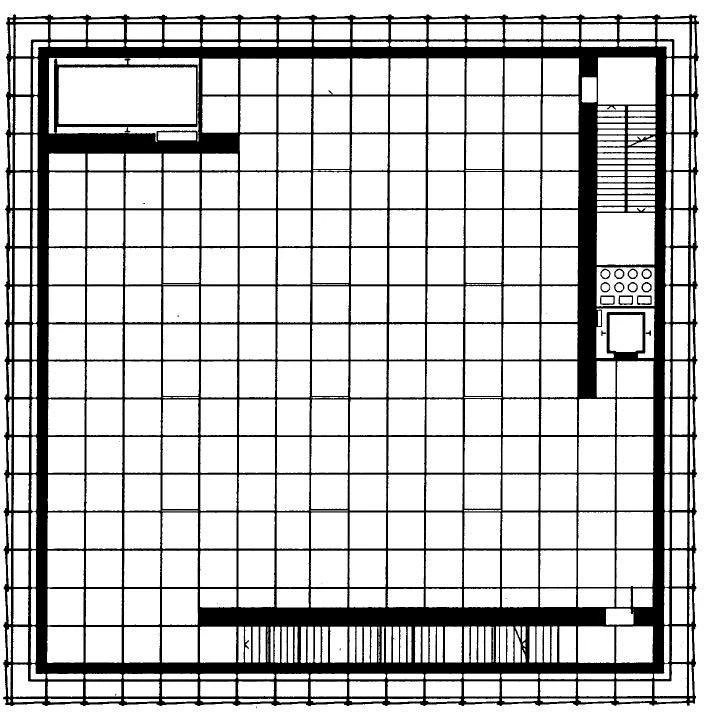

The Mies Award revealed the 34 finalists of its sixth edition in January, and held a second and final jury meeting on March 7 and 8 in the German city of Weimar, this year’s European Culture Capital. The trophy (which comes with 50,000 euros) was presented this month, in a ceremony held at the Barcelona Pavilion, to the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, who already was a favorite two years ago on account of the petrous, magical labyrinth of the thermal baths of Vals, and this time has capped the prize with the Kunsthaus of Bregenz, a lyrical, self-withdrawn construction in a small Austrian town on the shore of Lake Constance. Among the other finalists were Rafael Moneo’s Museum of Art and Architecture in Stockholm and three buildings located in Spain: a covered swimming pool facility in San Fernando de Henares by Mansilla & Tuñón, the cultural center of Villanueva de la Cañada by Juan Navarro Baldeweg, and the University Museum of Alicante by Alfredo Payá. None of these made it to the last round, where Zumthor had to contend with the Conference Center of Lucerne, a work of the French Jean Nouvel which the jury decided to save for a future edition; the Liner Museum in Appenzell by the Swiss partners Gigon & Guyer; and the villa in Bordeaux of the Dutchman Rem Koolhaas. But the Mies went to Zumthor, a secret master who recently won the generously funded Carlsberg Prize and thus now wraps up the most brilliant season of a tardy but intense career.

The Kunsthaus of Bregenz is a large glazed cube of an obsessive, hermetic perfection whose several exhibition levels, piled on top of one another, are faintly lit by the brightness that filters in through translucent ceilings. Outside, its rigorous geometry of glass gives no hint of the introverted intimacy of the rooms, which are closed to the landscape with screens of concrete that delimit near-Miesian spaces – spaces of a bare and silent exactitude, metaphysical in their daring abstraction and mystic in their negative nakedness. Encapsulated in the painful purity of these exquisite, self-withdrawn spaces, one cannot help understanding them as the reluctant reverse of the extroverted, shaken geometries of Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum, the best end-of-century reresentation of the populist commercialization of art, and also the first building ever to be designed with the sophisticated computer tools of the aeronautic industry.

This same industry now rehearses its most singular products in the chaotic theater of the Balkans, which has simultaneously witnessed verification of the vulnerability of the mythical F-117 Nighthawk, the stealth fighter of the Lockheed (a furtive aircraft whose unusual folded shapes have made it a cult object among architects), and watched the world preview of the formidable bomber B-2 Spirit, likewise invisible despite its 52-meter wingspan, built by Northrop Grumman in the form of a giant hang glider at the nightmarish unit cost of US$ 2 billion, a figure that pales any reprehensible architectural excess. The alliance has celebrated its fiftieth anniversary and the incorporation of three new members into the inevitable whirlpool of a conflict foretold, and Europe builds itself with vegetables and prizes while its tender, nubile body embraces death at the point of encounter of its grand cultural, ethnic and religious tectonic plates, where the abrasive friction of identities destroys people and landscapes. We know by now that if the Spanish people have a path that leads to a star, that star has four points, and we also know that the bull who abducted the maiden was the beast of blood and shadow of the Guernica, and that Schubert’s song is simply about the hypnotic horror of the woman being embraced by death.