Land architecture, but also architecture of the land. After three decades of work, Rafael Aranda, Carme Pigem, and Ramon Vilalta have obtained universal recognition for a stubbornly local oeuvre: the most media-savvy award of them all has distinguished an architecture oblivious to the media, because their constructions cannot be understood with-out direct experience. The volume published by Arquitectura Viva was therefore not so much a documentary record as an invitation to travel. The popularity that comes with the Pritzker Prize will turn Olot into an architec-tural pilgrimage destination, increasing the steady flow of visitors that already come to this volcanic region in search of the architectural epiphany sparked by the sensory contact with these works, embedded in their landscape and rooted in their site with the stripped violence of extreme relinquishment, with the rational determination of geometric rigor, abstract composition, and constructive refinement, with details that bring together violently tactile materials.

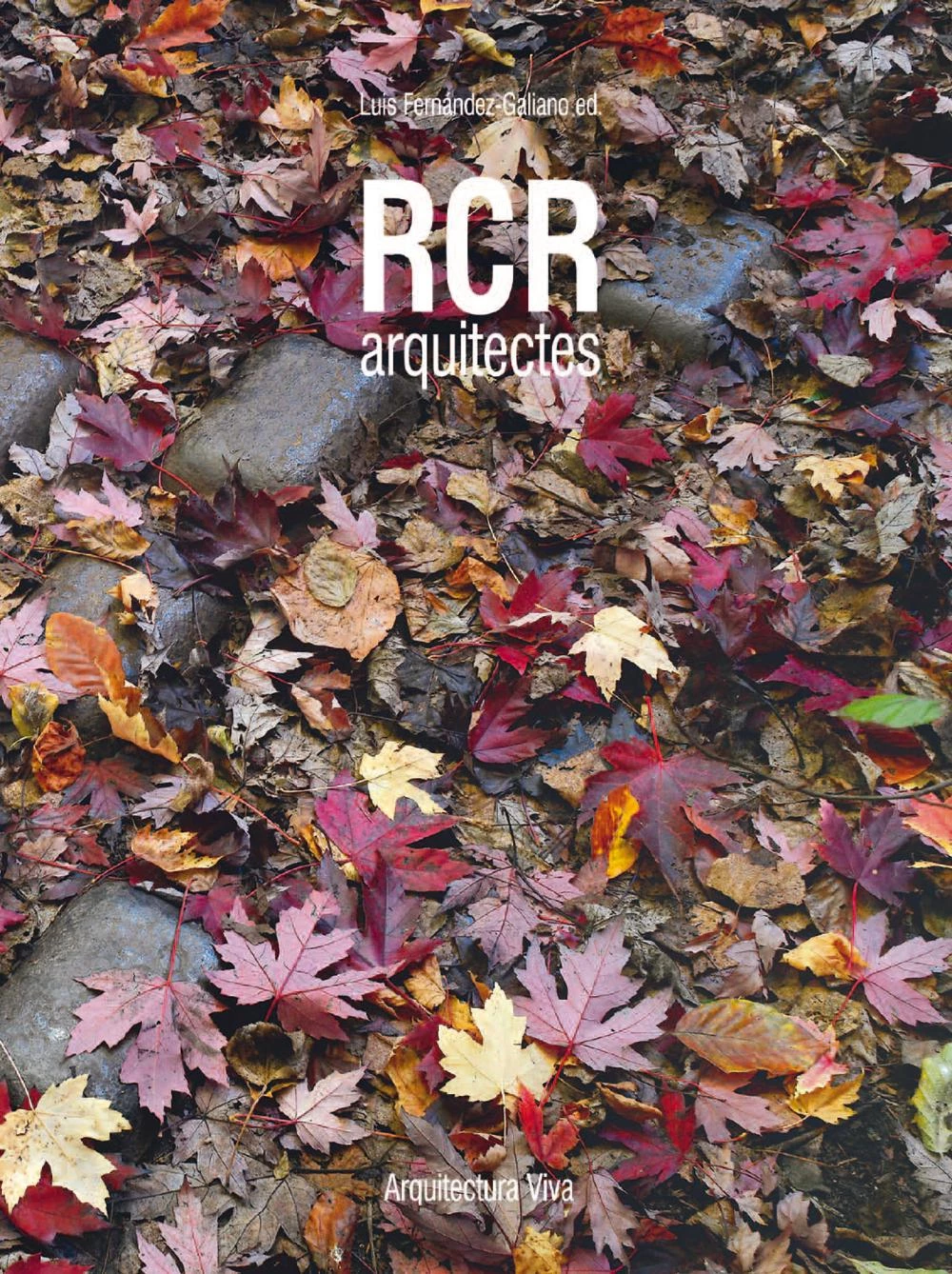

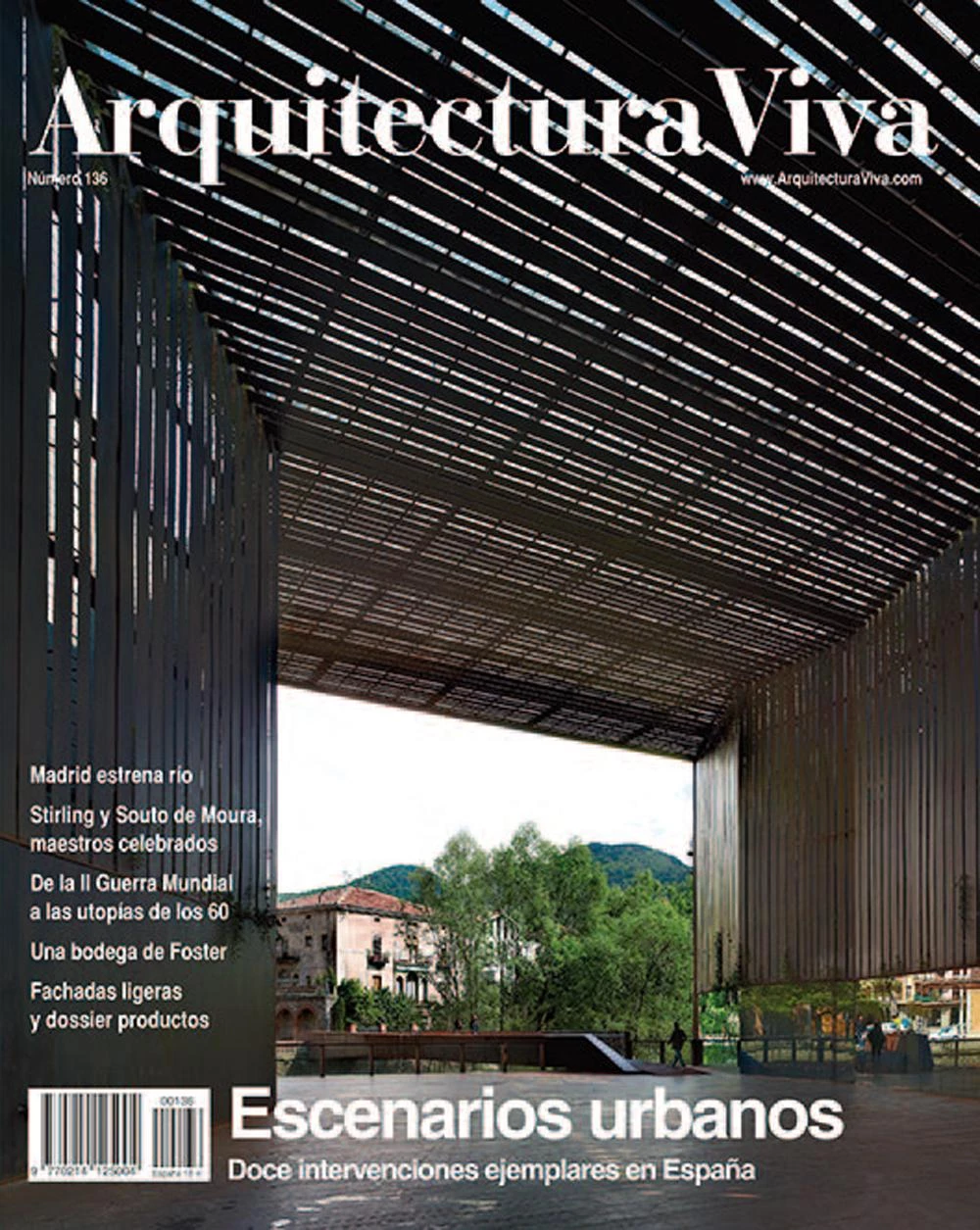

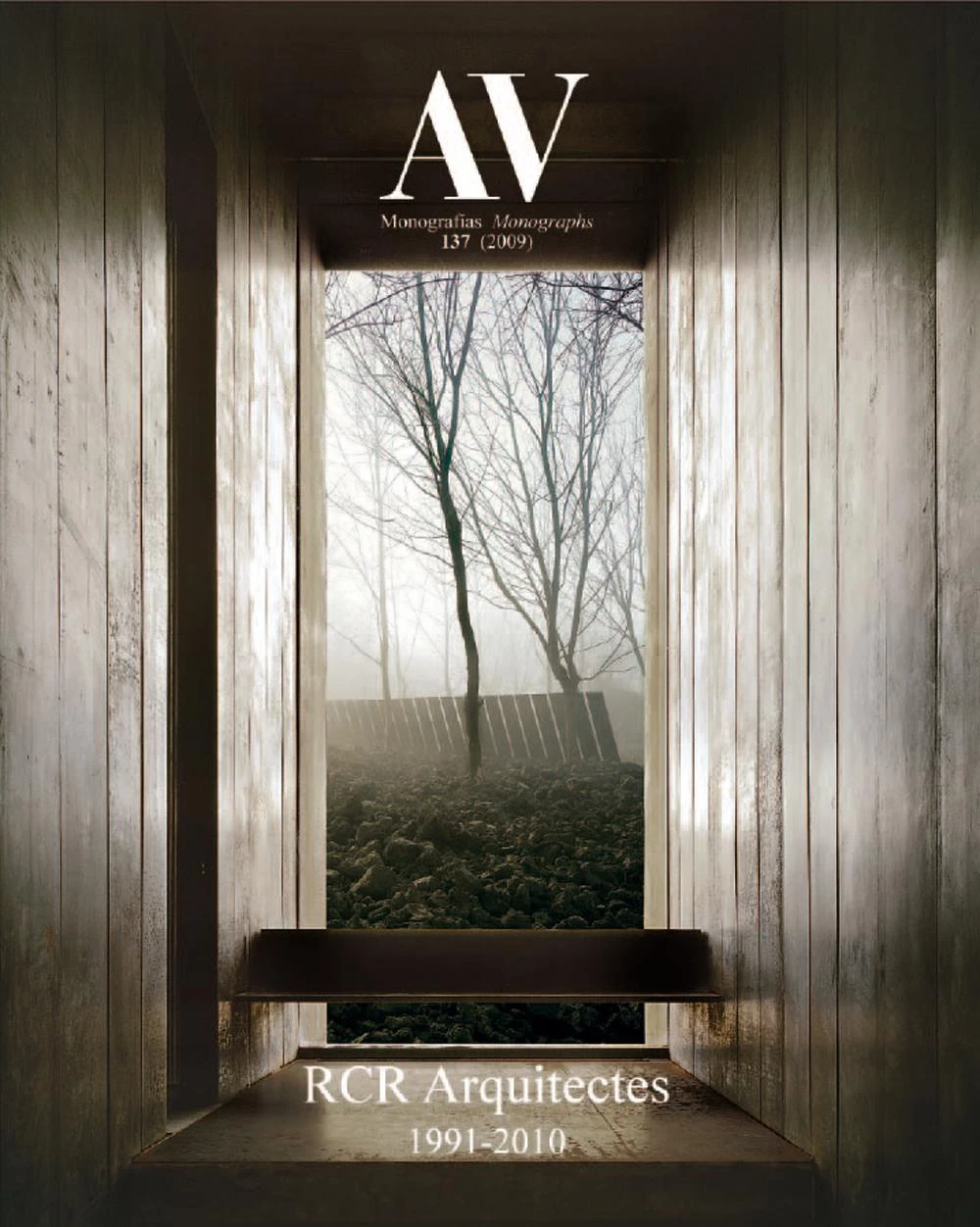

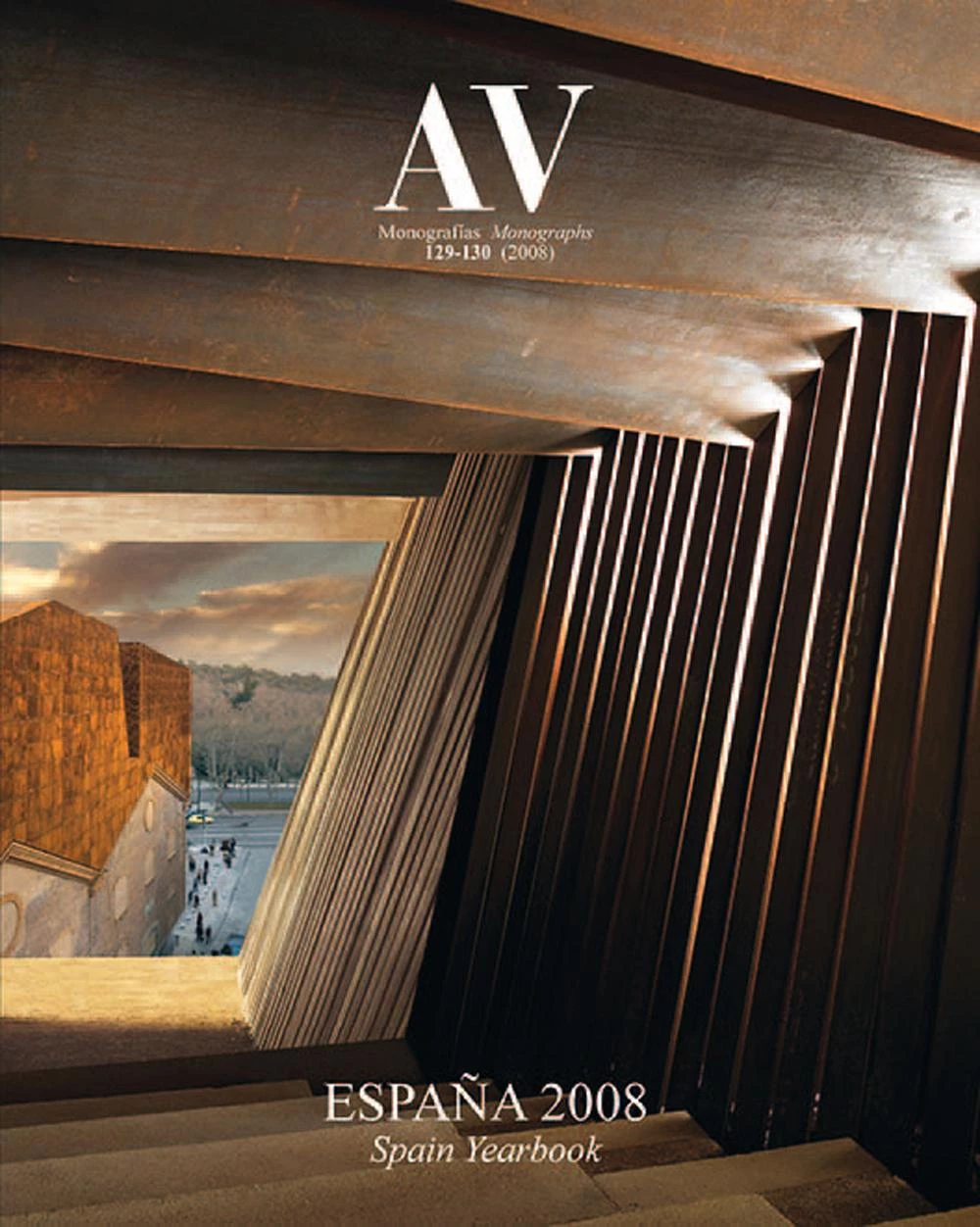

The six covers of AV/Arquitectura Viva, and that of the book on their whole career, convey the material quality of their constructions, the lyrical violence of their forms, and their profound empathy with nature.

Though the Pritzker will give their work great visibility, the RCR members had already received multiple recognitions. The exhibition on architecture in Spain organized by the MoMA in 2006 featured the Horizonte House, and the Spanish Pavilion at the Venice Archi-tecture Biennale that received the Golden Lion in 2016 included their Barberí Space: between these two major events, the Olot architects have seen their work displayed on many oc-casions and reproduced in countless publica-tions. Mentioning only those examples closest to us, their participation in the show ‘Spain mon amour’ in the Venice Biennale of 2012, the exhibition at the Museo ICO in 2016, or the half-dozen covers of AV/Arquitectura Viva are a few milestones that pay homage to this land architecture that is also an admirable ar-chitecture of the land, that combines romantic rauxa with rational rigor.

Based in Olot, the capital of La Garrotxa – a Pre-Pyrenean region in Catalonia, filled with extinct volcanoes –, RCR have built in their area a crop of works with a unique language that combines the romantic desire to blend with nature and to seek the sublime through extreme relinquishment, with the rational determination of geometric rigor, abstract composition, and constructive refinement, with details that bring together violently tactile materials.

It is an architecture at the same time essen-tial and eloquent, reductive as corresponds to what popular language calls minimalism, and at once expansive in its horizontal dialogue with the landscape, that is framed or perfo-rated with resolve. Julius Posener used to say about his master Hans Poelzig that he scorned “any architecture that could not be drawn with pee in the snow,” and those of RCR are created with the same expressive economy, which goes from the brushstrokes of the first watercolor – abridged like an ideogram – to the physical intervention of the architects in the shaping of land, the assembly of basaltic blocks, or the curling of steel bands, in an ‘action architec-ture’ that is summed up in gestures.

The traces of these artistic interventions are a series of buildings, pavilions, and parks so compactly woven into the territory, and in such exact harmony with its volcanic and abrupt beauty, that it is easy to imagine how they might serve as pedagogic and touristic lure, in a manner not very different from the one we can experience today with the work of Mario Botta in the Swiss Ticino Canton or with that of César Manrique in the Canarian island of Lanzarote. Though their projects nowadays reach other areas of Catalonia, European countries like France or Belgium, or even as far as the Gulf, the legacy built in La Garrotxa and its close sur-roundings makes these architects inseparable from the history of Olot.

In the end, any description of the work of RCR must resort to oxymoron. One may use geomet-ric landscapes, weightless gravity, or rigorous romanticism: these antithetic terms express the tension between a materiality of stark harshness and a lyricism of throbbing emotion; between a formal extremism that takes no prisoners and a sensibility that opens up to nature without reti-cence; between the heavy solidity of concrete or steel and the fragile lightness of glass or shad-ows, which blurs the building in atmospheres and reflections. Tactile and immaterial, their works belong to the earth and transcend it, are at once telluric and translucid, severe and gentle, frozen bonfires that warm up and char, leaving a gem residue in their resplendent darkness, exquisitely carved and covered by a patina of rust that mixes manufacture and meteor.