Museum Inc.

Today’s museums are companies which deliver identity. In the projects of M. Mansilla & Tuñón, this new profile is reconciled with traditional gravitas.

A museum costs the same as a soccer player, and a similar return is expected: ticket sales and titles. The city of Castellón opened its Fine Arts Museum on January 24, a week after Martín Palermo was incorporated into theVillareal club, and a week before Pablo Aimar joined Valencia. The $19 million cost of the building designed by the Madrid architects Luis Moreno Mansilla and Emilio Tuñón resembles the cost of importing Argentinian players (the forward of Maradona’s old Boca team has been signed for $14 million, and the centerfield of River fetched a price of $21 million), and the expectations are no different: audience influx, media impact, improvement of collective self-esteem. And if crowned with good games and wins, so much the better. This was festively expressed by Bilbao’s joke back when Frank Gehry’s eddy of titanium was but a project on paper: “And what do you think of the Guggenheim?” “Well, if it scores goals...” It did, and even the most reticent have had to acknowledge the profitability of this art contract of several digits, the same number of digits the Real Madrid club would later expend on the portuguese Luis Figo, yet another investment that is reaping dividends in the form of spectacle and league results..

The Museum of Fine Arts of Castellón houses its collection in a hermetic aluminum box, whose severe image finds an ironic counterpoint in the gigantic Venturian logo that provides visibility to the institution.

The Guggenheim bar cannot be applied to Castellón, but the vigorous ambition of Valencian prosperity will not settle for much less either. The City of Theater of Sagunto, the City of the Arts & Sciences of Valencia, and the City of Cinema of Alicante are just three representative projects of an autonomous region that has already carried out operations as diverse as Terra Mítica, one of Europe’s largest theme parks; the Biennial ofValencia, an art event that aspires to compete withVenice’s and Kassel’s; and the Castellón Cultural, a complex that includes the recently inaugurated Fine Arts Museum and the very active and critical Espacio de Arte Contemporáneo. From the vertiginous flight of the Alicante park’s phoenix to the radical and gay gaze of the Castellón art space, the Valencian Community offers a variety of attractions that is a cheeky threat on Barcelona’s lazy leadership on the Mediterranean coast. A Valencia soon to be part of the AVE high-speed railway system will hardly be content with expanding the IVAM (Valencian Insti-tute of Modern Art), to which the local architects Emilio Giménez and Julián Esteban are adding 9,000 square meters: the plan is to set the modern rigor of the crown jewel in a garland of facilities characterized by an extraordinary thematic and geographical diversity.

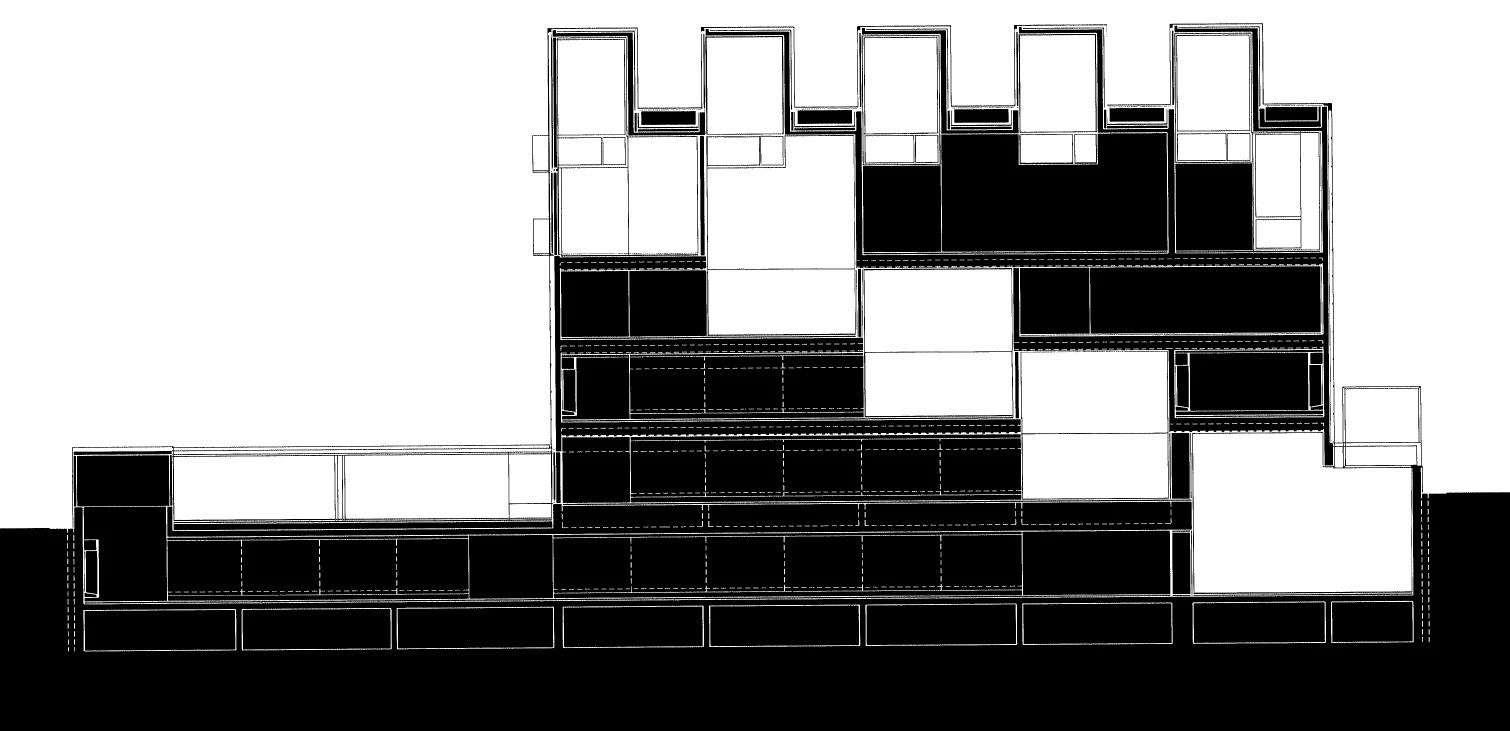

The opacity towards the street of this Levantine museum is inverted in the interior, where the rays coming in through the roof skylights give a scenographic quality to the cascade of two-story exhibition halls.

In the region’s northernmost province, the same economic buoyancy that has brought the soccer player Palermo from Buenos Aires to Villareal has also erected a box of concrete and aluminum to protect the historical ceramic pieces which are the more valuable part of the permanent collection, and which take up half the exhibition space of the new Fine Arts Museum. Situated in a dense and anonymous zone of the city, Moreno Mansilla & Tuñón’s building consists of a categorical and hermetic cube for the permanent collection, attached to an old mediocre cloister that has been refurbished to house the museum offices, and complemented by a pavilion for restoration workshops at the other end of the premises. The compact main volume closes itself to the degraded urban environment and illuminates its interior through a row of skylights, under which the galleries descend in a cascade. This spectacular sequence of double-height spaces, which permits diagonal views from the top floor all the way down to the sunken courtyard at basement level, gives the building a pleasant scenography which its severe exterior gives no clue of.

Lined with heavy, striated plaques of smelted aluminum which give it an at once industrial and refined look, this exquisite crockery chest announces itself on the busy main street with a splendid sign-latticework that reconciles the tactile gravity of the work with the publicity-oriented loquacity of the emblem. As in their previous Zamora museum, Moreno Mansilla & Tuñón have built a concrete cube with a rigorous floor plan and a dramatic section, that creates a contrast between the solid opacity of the walls and the luminous transparency of the interiors, and complements the compact economy of the interlocking volumes with the unexpected richness of diagonal patterns. But Castilian aridness relaxes here with the Venturian gesture of the monumental label, which with irony takes on the visibility required of the contemporary cultural enterprise. The museum of today is a commercial trademark that offers sublime experiences to visitors and tourist income and prestige to the city that accommodates it, and one is no longer sur-prised if Bilbao’s Guggenheim presents its annual report with a calculation of its impact on the Basque economy, nor if the Basque government awards the sculptor Chillida with a Tourism Prize for the contribution of the recently inaugurated open air museum of Zabalaga (an estate which houses the life-work of the artist) to the region’s recreational offer. If football figures must fill the grandstands with spectators, so must art and architecture fill our cities with visitors. Besides scoring goals.

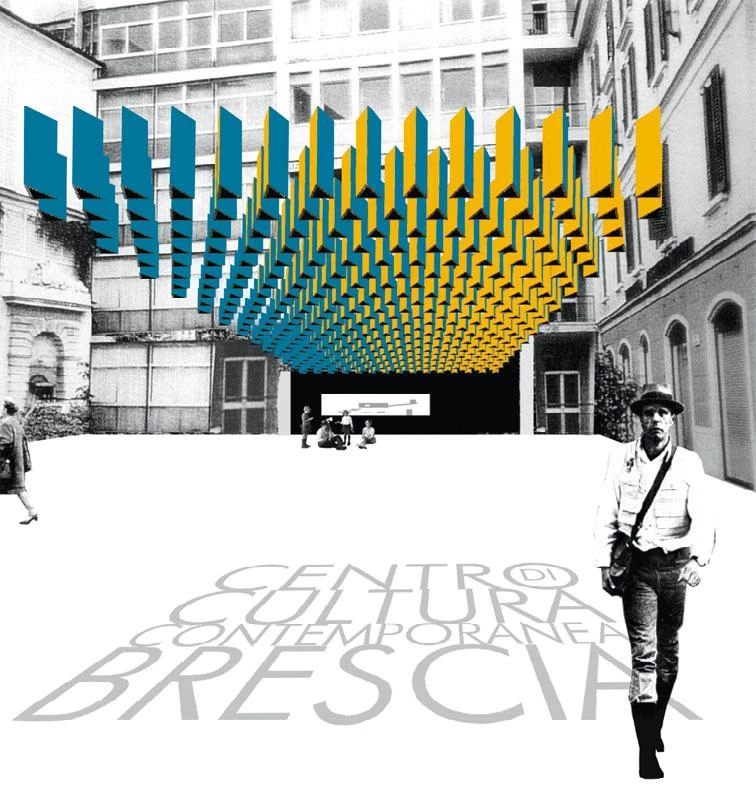

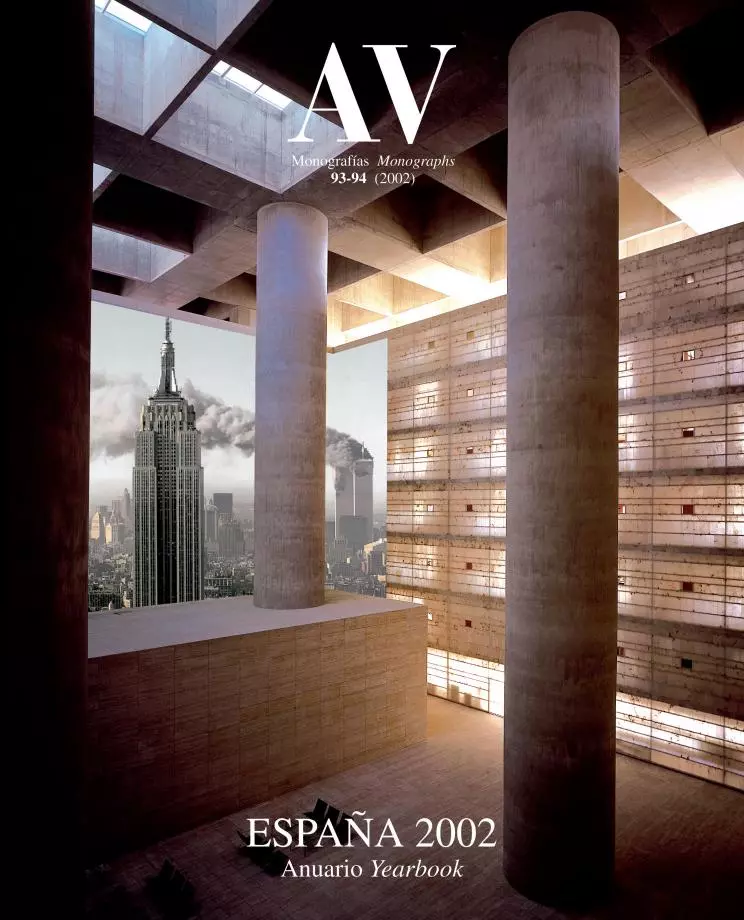

The Strict Filiation of the Neo-Bland School

Disciples and collaborators of Rafael Moneo from 1982 to 1992, Luis Moreno Mansilla and Emilio Tuñón participated in at least four museum projects of the Navarrese architect: the Museum of Roman Art in Mérida, the Miró Foundation in Palma de Mallorca, the Thyssen Museum in Madrid, and the enlargement of the Fine Arts Museum of Houston. This experience nourishes what they have carried out on their own. From the gravity of materials to the compactness of forms, and from expressive laconicism to a penchant for labels, many features of the Madrid duo’s work are directly related to that of their architectural father. The latest projects of Moreno Mansilla & Tuñón, however, use a significantly more graphic language based on their fascination with publicity billboards, and this toned down pop register rears its head in the colossal sign of their proposal for the enlargement of the Reina Sofía, in the labelled pavement and vibratile canopy of the Center of Contemporary Culture of Brescia, and in the polychrome claddings and informative walls of the Museum of Contemporary Art of León. The neo-bland current that has the modern classicism of the Italian fashion guru Miuccia Prada for a banner and the amiable moderation of the Spanish socialist leader José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero for political expression finds its best formal reference in these projects: Warhol and Beuys, color and geometry, publicity and construction. An elegant and low-profile modernity that silently registers the pragmatic temperature of skeptical times.

In later projects for museums (left to right, the MUSAC of León, the Reina Sofía extension proposal and the Center of Arts in Brescia), Moreno Mansilla & Tuñón have stressed the more graphic side of their work.