Modern architecture was born as much from optimism as from despair. After the systematic slaughter of the Great War, the young German architect Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus, a school destined to be the emblem and the incubator of the modern revolution. Its closure with the coming to power of the Nazis in 1933 would mark the end of the adventure of the European avant-garde, who dispersed or emigrated with the advent of totalitarianism on the continent.

The dawn of the modern in Feininger’s xylograph for the Bauhaus (1919), in Bruno Taut’s Alpine Architecture (1919) and in Mies’ skyscraper project (1921-1922).

In the stirrings of the 20th century, Germany had been the main scene of the dialogue between industry, architecture and the arts: in its attitude toward the machine, the Deutscher Werkbund had proven less nostalgic than England’s Arts and Crafts, and less visionary than Italian futurism; and as for its stance on the large firm, the lamps and buildings that Peter Behrens designed for the electric company AEG exemplified a pragmatic collaboration with industrial capitalism. It is significant to note the coincidence in Behrens’ studio, prior to the war, of those who would in the twenties be the protagonists of modern architecture: Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Gropius himself. But when the latter, following Germany’s defeat in the war of 1914-1918, put up the Bauhaus in 1919, the mood of technological optimism had turned into anguish and dispair in the face of the devastating power of the new mechanistic civilization.

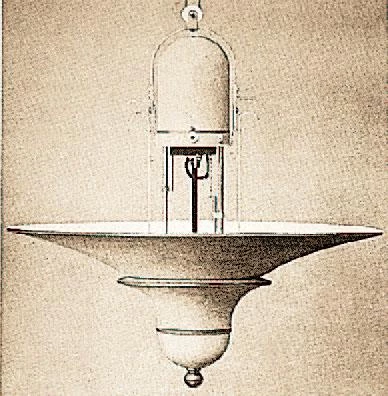

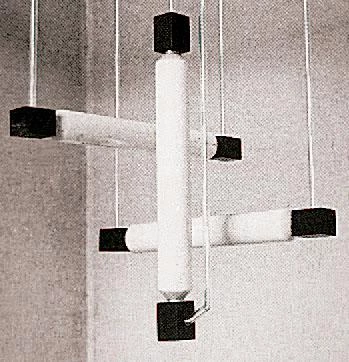

Modernity is forged combining the logic of industrial production, illustrated by Behrens’ lamp for AEG (1907), with formal elementalism, represented in an abridged manner by Rietveld’s lamp (1923).

Confronted with the collapse of the old social order, the architects and artists of the Bauhaus envisioned the luminous Utopia of a new order, and their first manifesto was illustrated with the crystalline, romantic forms of a ‘cathedral of socialism’, crowned with stars that lit the road to humankind’s spiritual and material redemption. The positivist technocrats of prewar years were now enlightened prophets who preached a return to the wisdom of the primitive and envisioned the reign on earth of an apolitical socialism, which would only come through abstinence and transcedental meditation. This was the climate in which Bruno Taut colored his ‘Alpine architectures’, magical cities of glass built amongst mountaintops and glaciers for a regenerated humanity; in which Erich Mendelsohn evoked the fracture of mechanistic space and time through the sculptural, expressionist forms of his Einstein Tower; and in which Mies van der Rohe drew his glazed skyscrapers, whose hermetic monumentality, transparency and purity made them genuine cathedrals of glass of an altogether new era.

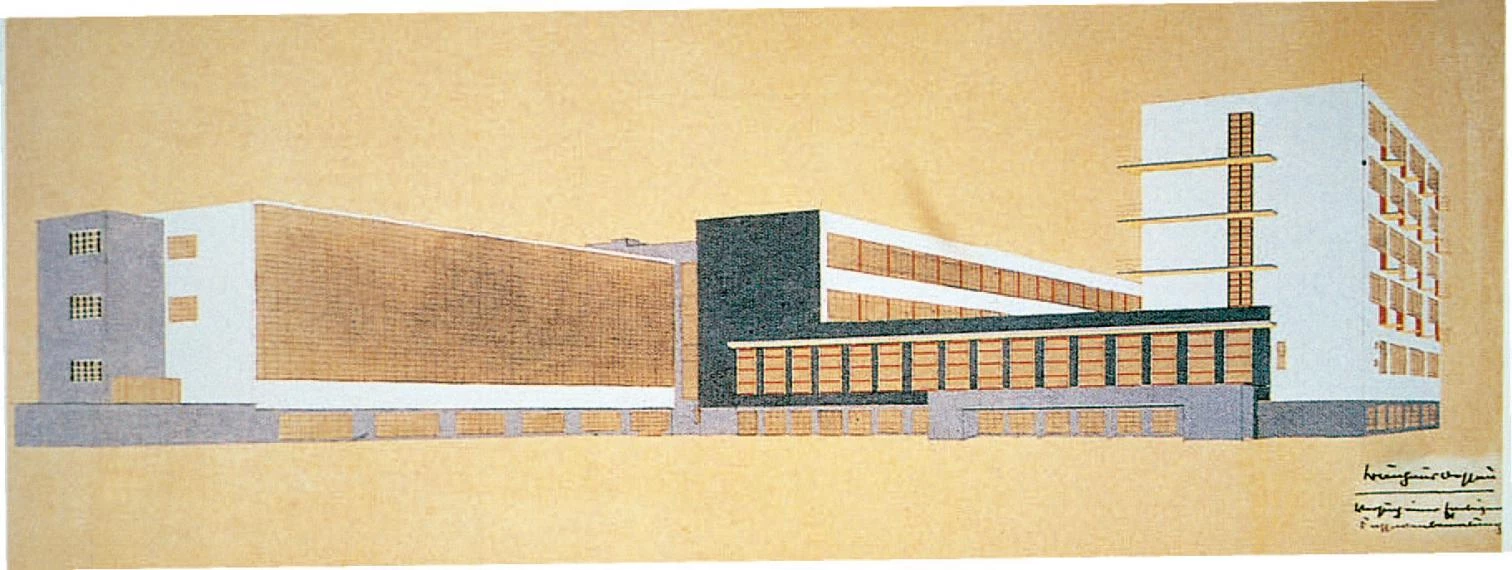

The formal and artistic revolution that took shape in the neoplasticism of Rietveld’s Schröder House in Utrecht (1923-1924) also influenced the rationalism of Gropius’ building for the Bauhaus in Dessau (1926).

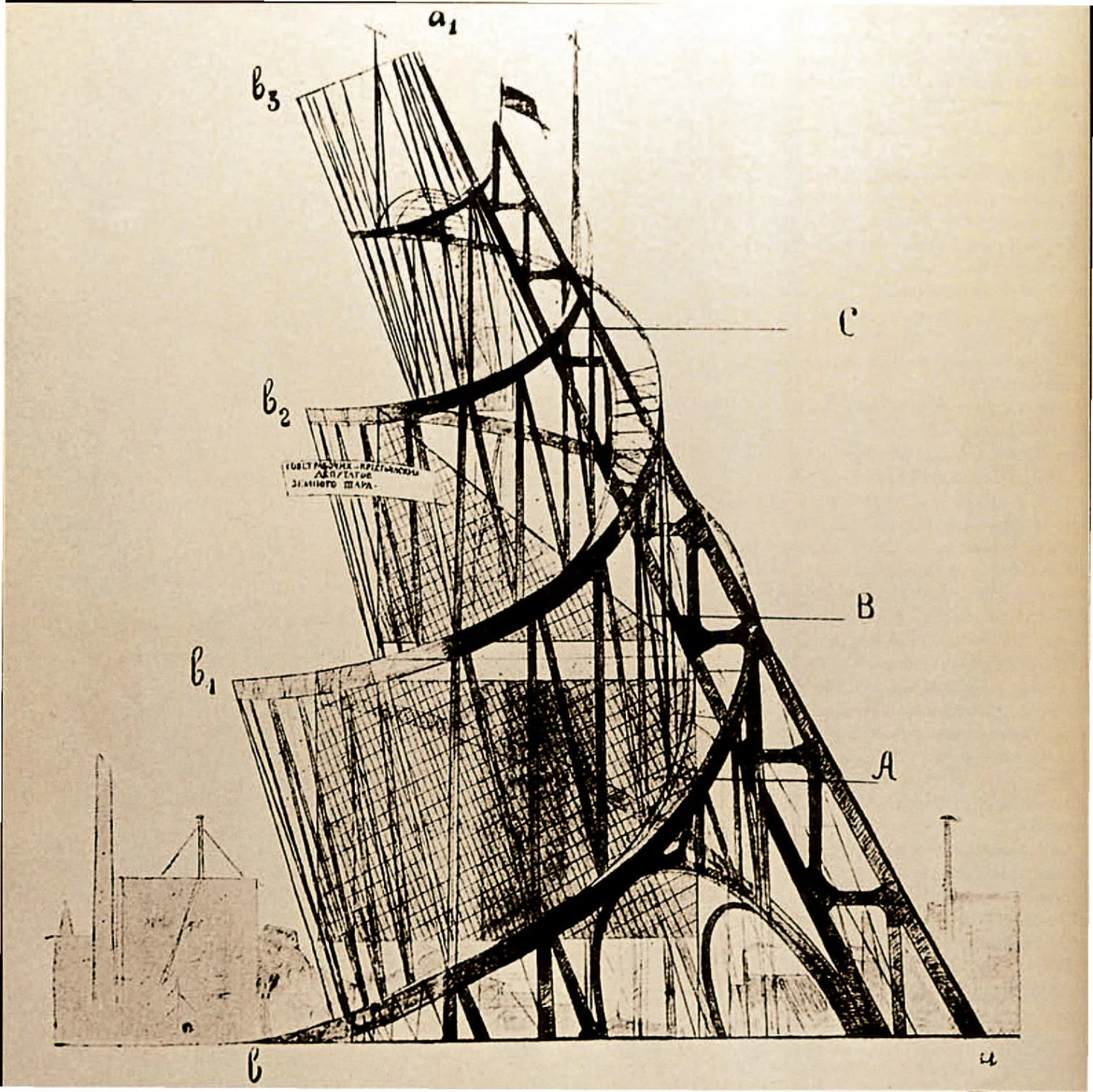

Meanwhile, another version of the new society was being conceived in Russia, likewise metamorphosed by the First World War. The conflict had brought on the fall of the old regime and allowed the Bolsheviks to initiate a colossal political, economic and cultural experiment. In the avant-garde fervor of the revolution’s early years, architects and artists together forged a new formal language, abstract and Utopian, that endeavored to represent the nature of the emerging society, merging the geometrical elementalism of cubism with the unstable dynamism of futurism in the mechanistic crucible of a civilization fascinated with technology as key to collective emancipation. Indeed, Vladimir Tatlin’s project for the monument to the Third International – a huge leaning spiral iron frame supporting a cube, a cone and a cylinder – unites the rationalism of basic forms with the diagonal romanticism of dialectical loops, and wonderfully expresses the visionary aura of the times – a moment best captured by this other, never-built and possibly unbuildable ‘cathedral of socialism’.

In 1923, Le Corbusier published Vers une architecture, the most influential manifesto of modernity, finding in contemporary machines and ancient buildings a shared beauty that resided in elemental forms. The same year found Mies van der Rohe in Berlin establishing the G group for the promotion of a pragmatic ‘new objectivity’, and Gerrit Rietveld putting up the Schroeder House at Utrecht, a rectangular construction of sliding panels and primary colors that constituted the first architectural materialization of the fusion of Mondrian’s neoplasticism and Frank Lloyd Wright’s spatial language, a synthesis carried out by the Dutch De Stijl group. One member of this movement, Theo van Doesburg, had visited Weimar the year before, in 1922, and now it was the Bauhaus that adopted geometric abstraction as the visual grammar of the school, while reconciling itself to the world of industry and machines.

The formal and artistic revolution that took shape in the neoplasticism of Rietveld’s Schröder House in Utrecht (1923-1924) also influenced the rationalism of Gropius’ building for the Bauhaus in Dessau (1926).

The dreamers became practical men, and if Gropius in 1923 could only express his return to productive optimism by decorating his office with neoplastic furniture, three years later the Bauhaus, accused of ‘Bolshevism’, found itself having to flee to Dessau. The move presented him with the opportunity to build a simple, abstract and functional building that survives to our days as a symbol of the modern dawn – an at once hopeful and troubled aurora that shone over the ominous ruins of the old order, but soon revealed the clouds of the tempest that would a few years later put an end to the Bauhaus and the innocence of that world.