Norman Foster has left his mark in the new Reichstag, and in the most unlikely spot: the reverse of the eagle that presides the Bundestag sessions. In the Federal Parliament of Bonn, the popular fette Henne was stationed on a wall, but in the glazed precinct of Berlin, the ‘fat hen’ hangs over the presidential dais, showing its back to those using the perimetral gallery. The British architect had to design a reverse for the emblem of Germany’s legislature, so he used the opportunityto outline a smile in the bird’s profile, and then sign his name under the wing. But prior to all this, the redesigning of the Germanic eagle had sparked heated controversies, with more rapacious new versions ending up having to succumb to the traditional image. In the final analysis the smiling, cordial eagle sums up the attitude that has accompanied the rebuilding of the Reichstag, and in more general terms, the spirit with which the German people and their representatives have carried out the shift from Bonn Republic to Berlin Republic.

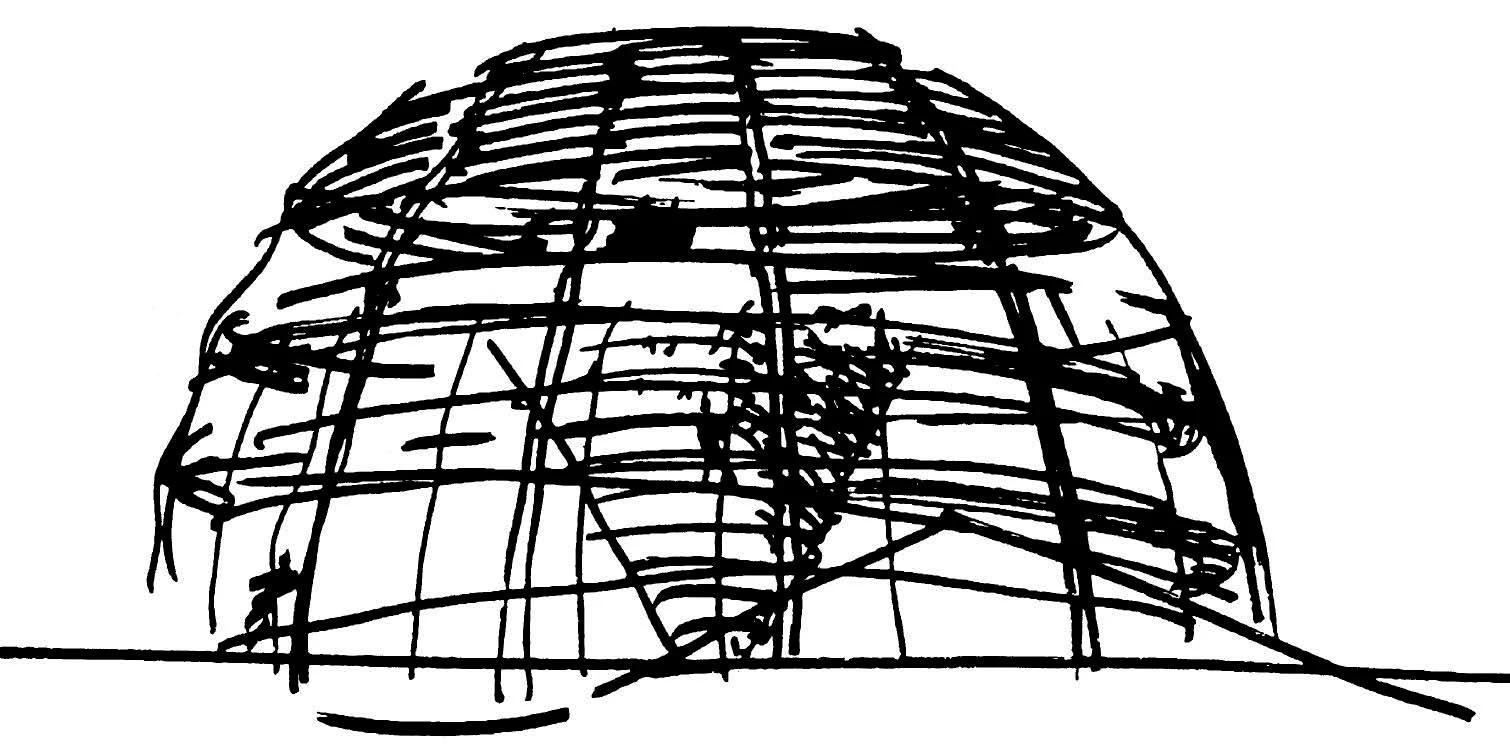

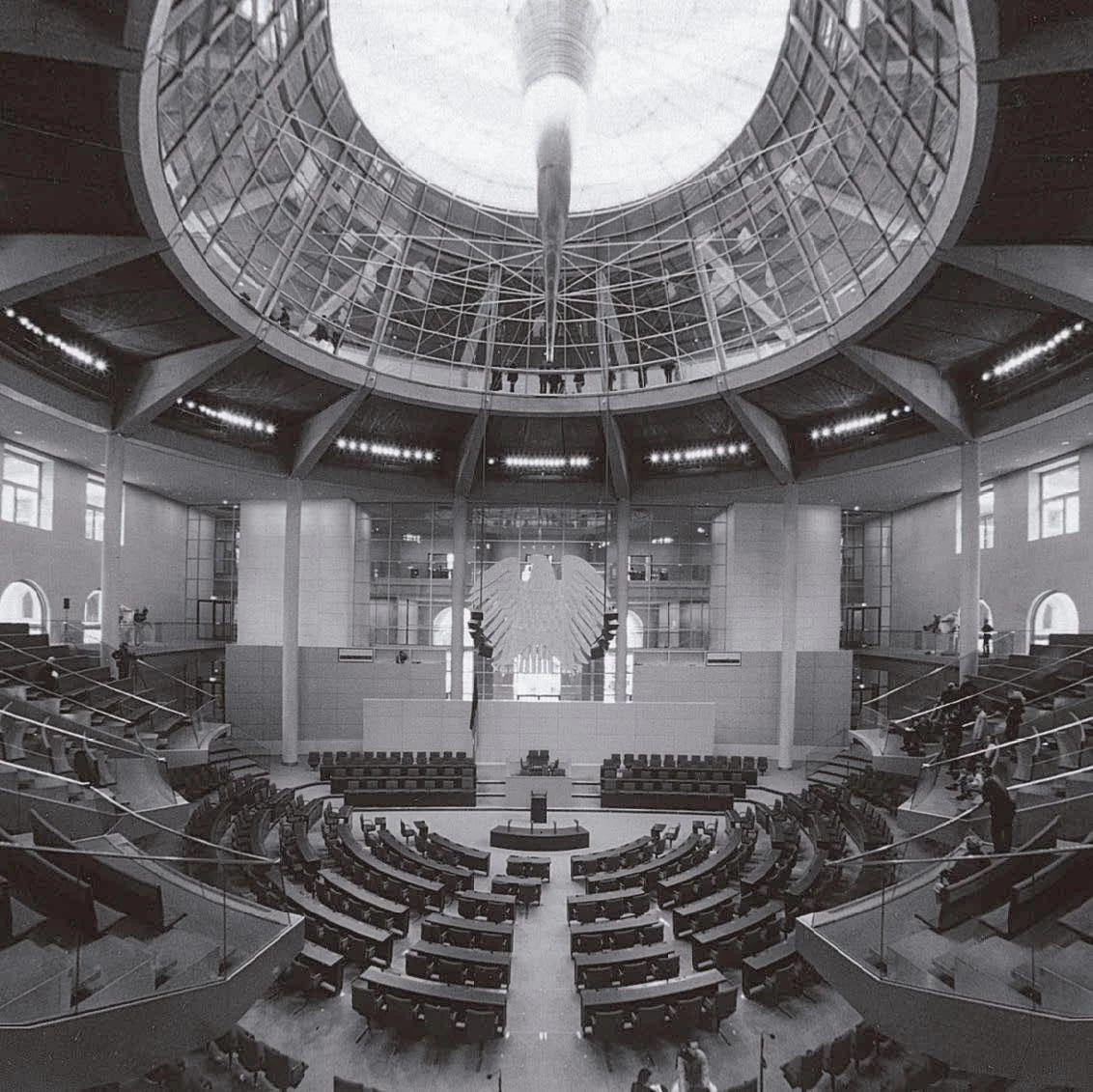

With a new glass dome that evokes the original one while transforming its symbolic content, the Reichstag tries to approach critically its own difficult history, which coincides with that of the nation itself.

The neo-Baroque mass that Paul Wallot completed in 1894 was never Berlin’s most popular building. Its glass dome was originally meant to be a democratic replica of the hermetic domes of churches and royal palaces, so William II and Hitler would equally loathe the building and the institution it housed. But people who suffered the consequences of German expansionism inevitably associated it with the aggressive militarism of both, and the emblem of Nazi defeat continues to be the picture of a Soviet soldier brandishing the hammer and the sickle over the rubble of its roof terrace. Such ominous memories made it seem like a risky thing o return Germany’s highest legislature to its original site, and the hypnotized fascination that Christo’s 1995 wrapping aroused may have been a collective release of emotions about the ritual cleansing of the building.

Designed as a beacon by night and a lookout by day, the dome of glass scales that crowns the Reichstag encloses a conical cascade of mirrors which illuminates and ventilates the plenary hall situated below.

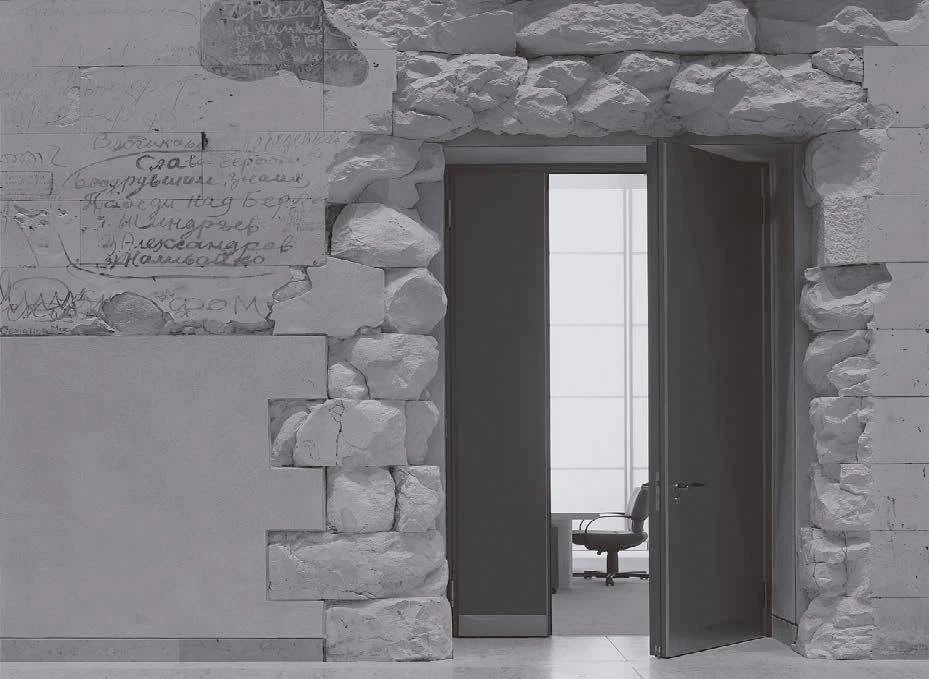

Foster’s project – which after four years of construction work and US$ 330 million spent was inaugurated in a simple ceremony on April 19 – interprets the ambiguous nature of the building and the contradictory sentiments it awakens with extraordinary intelligence and sensibility. On one hand it is a vigorous emblem of a healthy German democracy, a luminous landmark in the urban musculature of the new Berlin, and an optimistic example of the technical strength of German industry. On the other hand it is a manifesto that affirms the sovereignty of the people by accommodating the public in the spectacular lookout of the dome, way above their political representatives in the chamber; a living museum of Germany’s dramatic history that does not conceal the scars of demolitions, fires and occupations, including numerous graffiti left by the Russian soldiers who took over the building in the year 1945; and an eloquent discourse on architecture’s responsibility toward the environment, expressed here through the emphasis on natural lighting and ventilation, the use of recyclable combustibles, and a radically lowered emission of pollutant gases.

All this political, historical and ecological exemplariness could well have given rise to a solemn stiff building, but what makes this monumental work so meritable is, precisely, its friendly accesibility and naturalness. Embraced by two spiral ramps and pierced at the center by a colossal cascade of mirrors that both illuminates and ventilates the plenary session below, the glass-scaled dome is a torch by night and a lookout by day, a glittering hill that guides us in the dark, and a theater stage that opens to the spectacle of the city and the spectacle, too, of curious crowds roaming the ramps and multiplying in the magical quicksilver of the multifaceted cone. Wounded by the abrupt slashes of constructional pentimentos and lined with naïve or obscene inscriptions in Cyrillic characters, the interior of the old Reichstag is now colonized by sober corridors that have transparent parapets and leave chinks of light between a violent past and a routinary present, and the ulcers of memory are cauterized by the pasteurized placidness of aseptic offices. The huge plenary hall projects the cantilevered petals of the guest tiers over the austere desks of the legislators, and the whole thing is crowned by the glass ring that serves as the press room and by the blunt vertex of the sword of metal and air that hangs from the dome, putting the heart of the Berlin Republic under the serene light of a smiling eagle.

While the Russian graffiti point back to the dramatic history of the building, the German shield’s eagle has been made to smile from its reverse side in the new Reichstag location, thus summing up the optimistic spirit of today’s Germany.

The Reichstag was indeed a building weighed down by rubble, physically and symbolically. It took five months and 35 trucks a day to remove the material produced by the demolition, but it will take other means and much more time to get rid of the symbolic rubble. The first snag lies in the very name of the building (Reich means empire) which invokes the ghost of Bismarck as it does the phantom of Hitler and his thousand-year Reich; the extravagant solution has been to call it the ‘Deutscher Bundestag-Plenarbereich Reichstagsgebäude’ (German Federal Assembly-Plenary Area, Imperial Assembly Building), a denomination nobody bothers to use. Another hitch is the dome, which evokes not only the glories of William II but also the megalomaniac Kuppelhalle that Albert Speer designed for the symbolic center of a future Nazi Berlin, that, after victory in the war, would rule Europe with the name of Germania; here, by turning the dome into a public lookout, Foster transfers the solemnity of architectural form from the realm of despots to the friendlier field of urban spectacle.

But the biggest problem of the Reichstag is that its century-old existence connotes the continuity of German history despite the rupture occasioned by the Holocaust and the Allied Occupation, traumatic surgical facts which render Auschwitz atonement and fraternity with occupants inseparable. Such fraternity is expressed in the parliament through an installation by the French Christian Boltanski and a luminous screen by the American Jenny Holzer. These two works of art, along with the Russian graffiti and the project of the British architect pay tribute to the four powers that occupied Berlin in the postwar period and exorcized the demons of a country shattered by guilt and memory.

At the building opening, Gerhard Schröder would quote the Albanian Ismail Kadaré to justify the flight over the Balkans of the German eagle, at war for the first time since 1945. Days later, Oskar Lafontaine would remind the chancellor of the danger of humiliating Russia as well of Germany’s debt to the Slav Gorbachov. But the fette Henne has been installed in Berlin amid Russian graffiti, and those invited to the Spartan reception afterwards drank a toast, with beer, to a prosperous and friendly bird that has made memory its discipline and its shield.