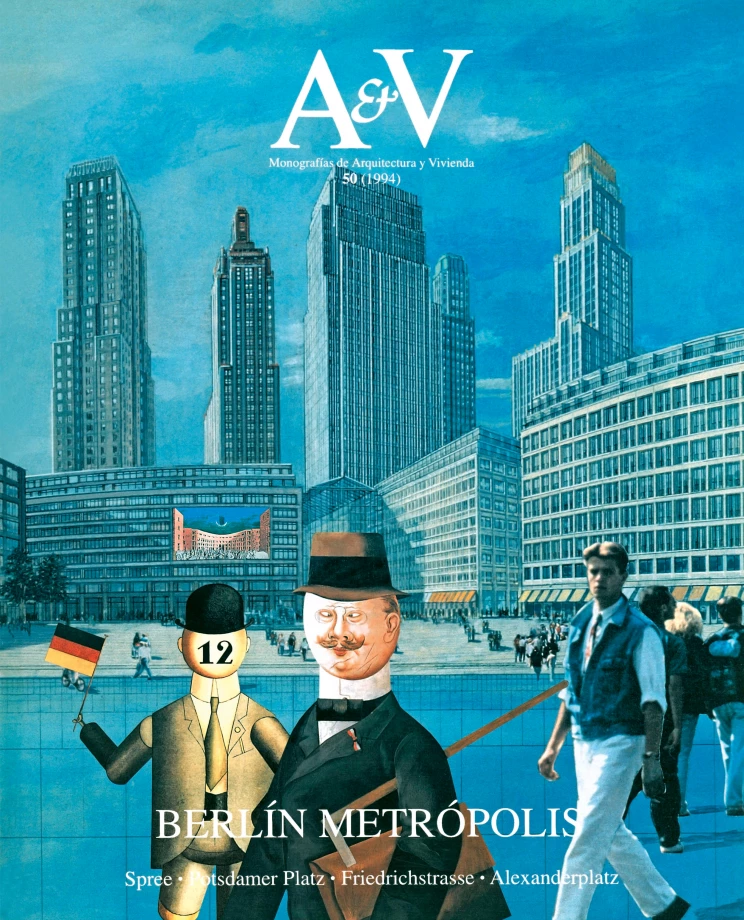

George Grosz, Metropolis, 1916 -1917

The 20th century ended on November 9, 1989. The fall of the Berlin wall abruptly closed a historical period, and the Cold War was followed by several hot wars and an icy peace. The melting of conflicts frozen by the battle of the blocs has given rise to local floods and avalanches. Paradoxically, the world that was to dole out the dividends of peace has become a more unstable and chaotic place than that which was subjected to the paralyzing bribery of nuclear balance. The planet finds itself dragged into a vertigo of technical and ideological change that turns social and economic relations upside down, modifies the territory and the city profoundly, and alters even the climate. There is no guarantee that this process is headed anywhere, not even that it can be. Though comforting to think that no one is to blame, it is disheartening to know that there is no cure for it either.

If Berlin arouses such melancholic reflections, it is doubtlessly due to the fact that it is not a city. Today, Berlin has become a symbol, or more modestly, a metaphor. Forced for decades to be a showcase and a trench, Berlin today is an accelerated and busy beehive, muddled by agitation and deafened by the buzz of machines. The language of cranes is its only mime, and the Esperanto of building orchestrates the insomniac activity of this ambitious and boundless Babel. In the clamor of construction, some meticulous grammarians get tangled up in orthographic matters. Yet this does not seem to alter the din of busy voices very much.

While the architects debate on the orthography of the facades, the rebuilding of the capital of Germany uses the lexicon and syntax o f developers. As during the times of Franz Biberkopf, the city suffers the violence and vertigo that accompany the stalwart and sturdy building of a metropolitan future, in a whirlwind of multiple and confusing activity that reflects or sums up the swift disorder of the planet. In 1929, Alfred Doblin put these words in the mouth of his protagonist: “On Alexanderplatz they’re lifting the pavement for the metro. You have to walk on boards... Rumm rumm, goes the steam roller loudly on the Alex, in front o f Aschinger... They move on the ground like bees. They’re building and doing their slipshod work by the hundreds, day and night... On the other side of the street they’re razing everything, all the houses near the belt line, where do they get the money, the city of Berlin is rich, we pay our taxes... I destroy it all, you destroy it all, he destroys it all.”

It is easy to imagine that the Berlin of 1994 would have inspired Franz Biberkopf similar lines. Five years before the fall o f the Wall, A&V dedicated its maiden issue to the city, and at the time we imagined the bewilderment that would have invaded the protagonist of Berlin Alexanderplatz on seeing the desolate, silent and aseptic landscape of the IBA city. Five years after that historic event which brought the century to an end, and coinciding with the tenth anniversary of the magazine, it has been A&V’s wish to return to Berlin with issue number 50, thus completing a circle. As much as we are faced with the agitated, dynamic and turbulent panorama of a metropolis in renewed gestation, our interpretation zeroes in on two axes and two centers that articulate Berlin’s four cardinal points. It is a more analgesic than diagnostic reading. But maybe we write the world to cure ourselves of it.