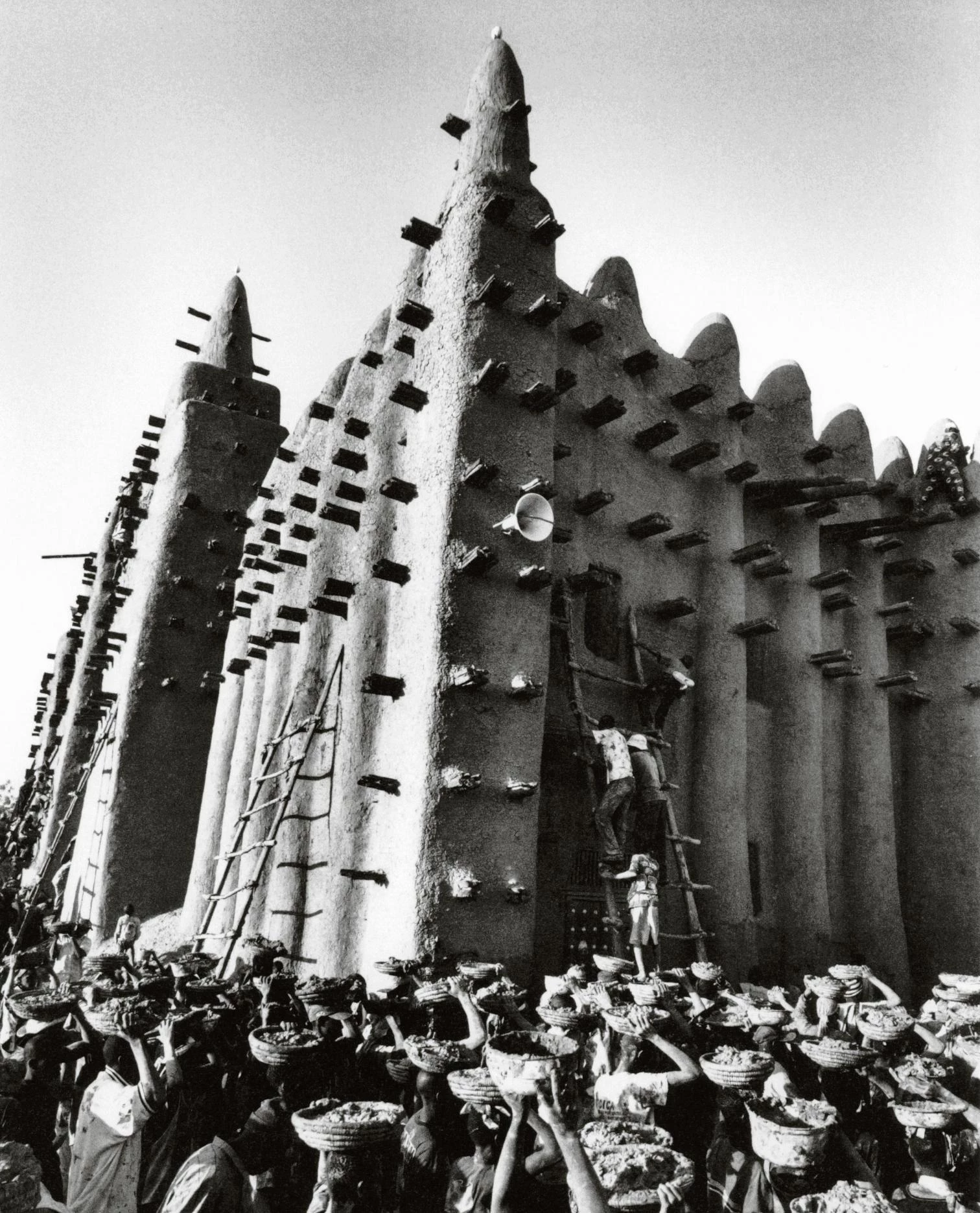

Luis Monreal, Tasbih. Instants d’un monde en transit, 2020

Monuments molt: they change skin, change image, and change meaning. As living heritage, they renew their renders and their walls, transform their outer appearance, and modify their symbolic content; and as vulnerable heritage, they experience decadence and neglect, give testimony of their ruins, and are reborn as facsimiles or replicas. Over a century ago, in ‘The Modern Cult of Monuments,’ Alois Riegl taught us that, aside from their historic value, monuments possess the value of age, because the traces of time apparent in their material decay make us aware of their organic nature. Constructions are no less fragile than us, they are no less perishable, and they are no less susceptible to being cast into the abyss where oblivion dwells. All of them mutable and ephemeral, monuments and people see matter and memory vanish in the current of time, and only the tenacious regeneration of buildings and lives delays their disappearance.

The Great Mosque of Djenné is the world’s most impressive adobe construction, and the most important monument of Sudanese architecture. In the inner delta of the Niger River, Djenné was, like Timbuktu, a hub of Trans-Saharan trade and Islamic knowledge, and the present mosque was raised in colonial times over the ruins of a previous one. Once a year, when the rain season ends, the mosque must repair damage by renovating its facade with banco (a timeless recipe that mixes mud, straw, shea butter, and baobab dust), a task fulfilled in one day by the whole community, and that has become a unique ritual. The archaeologist and photographer Luis Monreal – with whom I was fortunate to travel across those areas of Mali, off limits today due to the presence of an Islamist guerrilla – documents in his latest book the extraordinary regeneration of this living monument, which is reborn periodically in tune with nature.

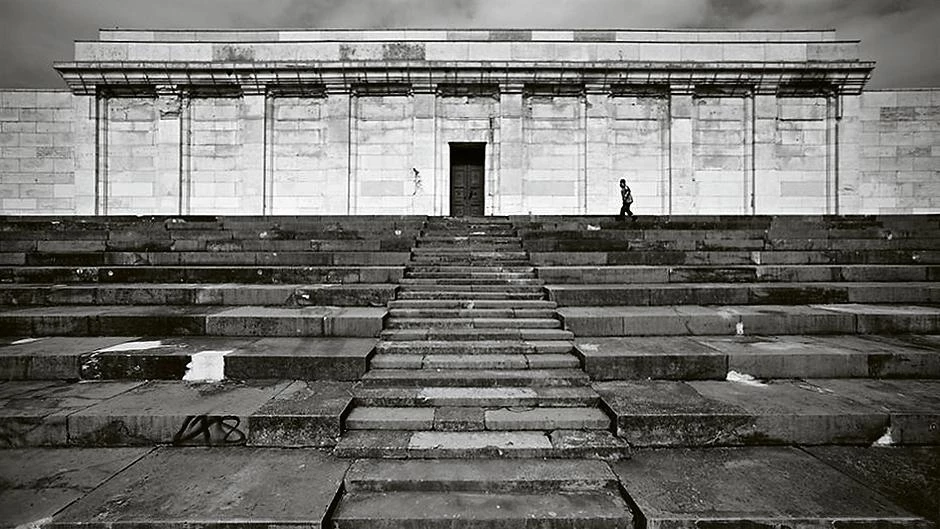

In violent contrast with this ceremony of fertility, and coinciding with the 75th anniversary of the Nuremberg trials, Germany has decided to preserve the ruins of the Zeppelinfeld, where Speer built the huge stand from which Hitler presided Nazi rallies. Here, paradoxically validating the architect’s Ruinenwerttheorie (which argues that buildings should be designed considering their beauty and magnificence when time has turned them into ruins), the country proposes changing the meaning of the work, so that the remains are preserved as a reminder of an ominous past that must not be repeated: a ‘lieu de mémoire’ that is also a gesture of expiation in the city that enacted the laws that led to the murder of six million Jews. If monuments can be renewed physically and symbolically, changing their face like animals shed skin, they can also be ethically and emotionally regenerated by surviving as a ruin, a reminder, and a warning.

Tribuna del Zeppelinfeld, Núremberg