The long career of Miguel Fisac is orchestrated here in three movements, linked to the Renaissance triad vis-cupiditas-amor (strength-ambition-love), chosen so that the dialogue between nature and history may cover the three stages of his work (related to organs, bones and skins) in three periods of Spanish life: the isolation of the 40s and 50s, the takeoff of the 60s, and the changes of the 70s and 80s.

The restless vis of the young Fisac is channelled through a scientific campus in Madrid and an array of academic and religious projects in Castile that express well his dual inclination towards knowledge and the spirit, on top of a lively curiosity that leads him to cross the almost impervious borders of an isolated country, and change his outlook from the academic classicism and metaphysical severity of his beginnings to the functionalist empiricism and cautious organicism of his later professional work. Those organs of autarchy would be ideological offshoots of a regime oblivious to the movement of the world, but also fertile wombs where the seeds of change would begin to grow.

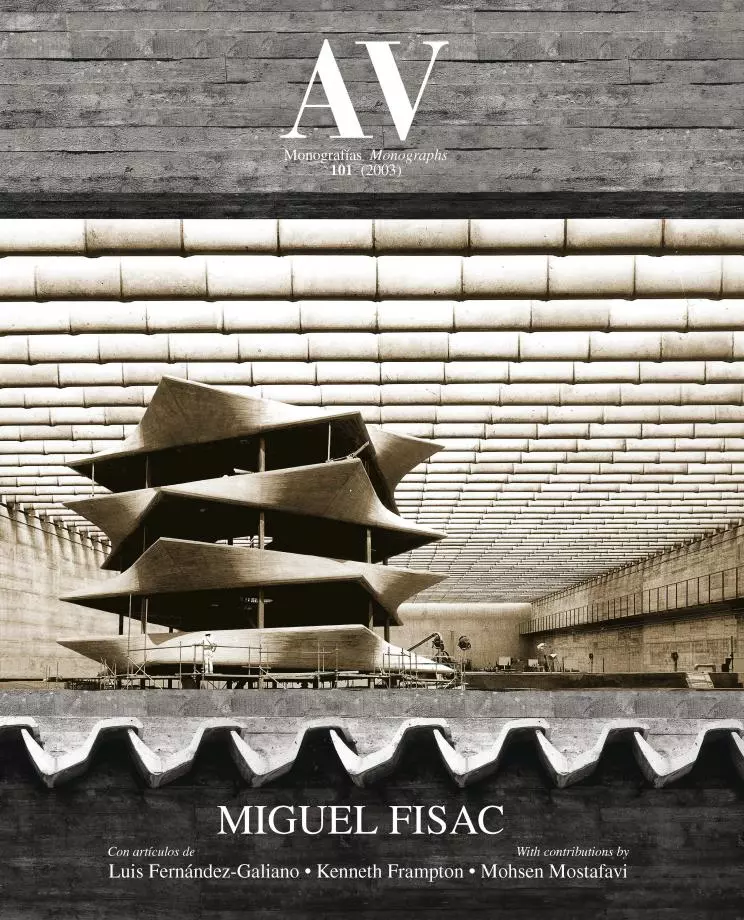

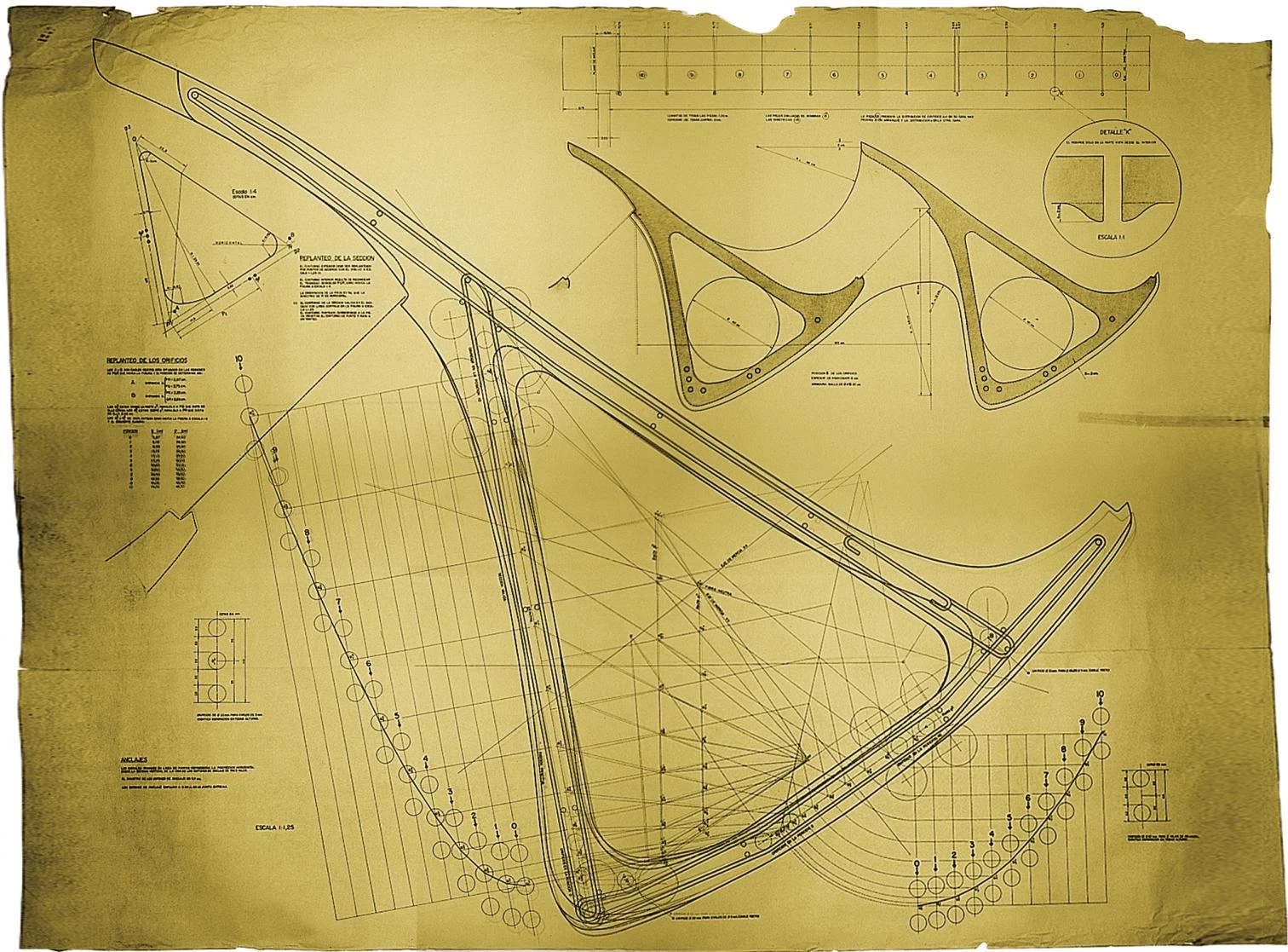

The firm cupiditas of the mature architect delivers a broad harvest of innovative works, industrial buildings for laboratories or factories and research headquarters (located mainly in the Spanish capital) that widely use his most important invention, the prestressed hollow concrete beams which he named bones, and whose elegant technical and sculptural optimism convincingly illustrates the moment of economic boom in a country which is gradually opening its doors to goods and ideas from abroad. Those bones for development would give structural support to the growth of that prosperous period, and serve as symbol of the success of an architect in tune with a fast-paced country.

The introspective amor of the last Fisac is neatly displayed in a series of works that go all the way from the churches and welfare centers in Madrid to the hotels and offices in tourist areas, buildings where he experimented with a new type of façade made using flexible formworks – a construction system that with the help of plastic sheet and wire gives concrete a soft or tormented appearance –, an antithetical ornament which reflects the uncertainty of the times and the vicissitudes of his own career. These skins in transition are doubly so, because they refer both to the shallow changes in a postmodern democracy and to the interior mutations of an increasingly secret architect.

The canonical humanistic triad marks and closes the territory of Fisac with a circular triangle that moves from pure to practical reason, and then to the critique of judgement, covering the itinerary between science, ethics and aesthetics to illustrate with this geometrical oxymoron the opposition virtus-fortuna, the ultimate dilemma of a professional or a personal trajectory, and that the biography of this universal Spanish architect bridges with unique success.