Fire and geometry humanize mud. In the Genesis, the warm divine breath awakens lifeless matter; in the oven, burning air endows formless matter with its final shape. Biblical or ceramic, the transit from raw to fired clay is a civilizing threshold that blows life in through heat and form; after all, fire and order are sure signs of human habitation. To that mythical and archaic gravitas, brick adds its anthropological dimension: “handy-sized unit of building material”. The old manuals’ definition refers to the size of the handling body, and this ergonomic mention of the builder humanizes a geometric universe modulated at the service of assemblies and joints: the brick length with which we still measure the thickness of facades is a bright residue of a world that was measured with handspans and cubits because it was built with arms and with hands.

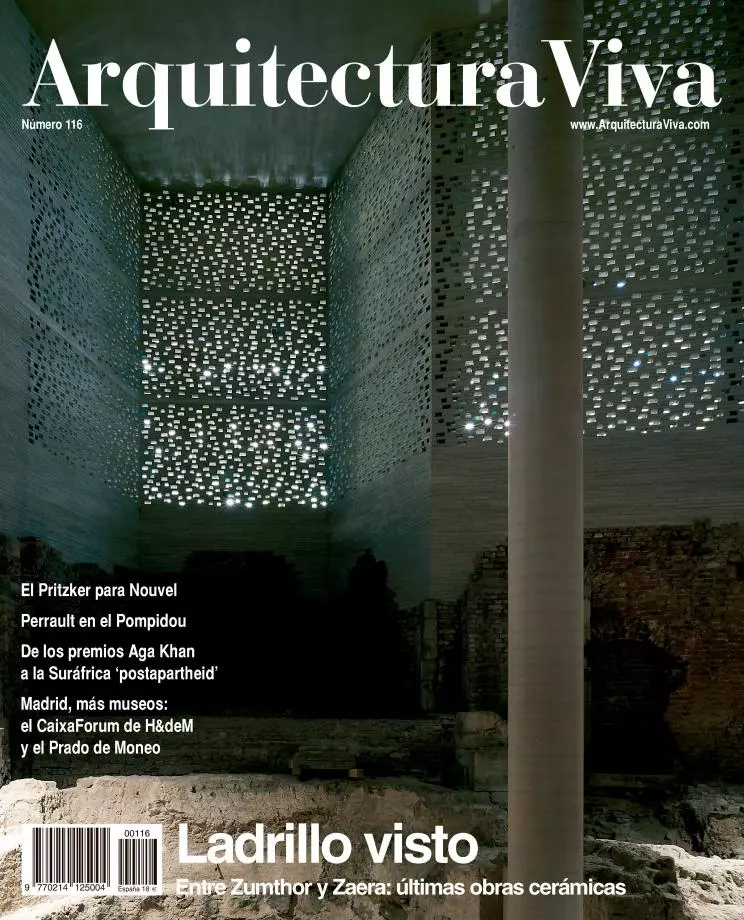

This anthropic brick is also the prismatic cell of the ceramic works, and the dimensional control of its fabric the proof of the rigor of its project. From walls to roofs or pavements, the exact grids of bricks, slabs and tiles have been the litmus paper of the wet construction that hoped for the precision of dry joinery, reconciling the tactile seduction of baked earth with the intellectual pleasures of visual order. In spite of this effort to attain aesthetic and technical redemption, ceramic construction suffered the indifference of doctrinarian modernity, and such refined elements as the lightened brick – which in combination with the half-joist produced floor slabs of great economy and easy construction – or the Arab tile – shaped on the craftsman’s thigh, and versatile in its overlapping geometry of valley and cover tiles – became icons of backwardness.

Today, brick is associated with the real estate boom, in a frenzy of bad press illustrated by the tongue twister “España está enladrillada, ¿quién la desenladrillará?”, and with a pejorative diffusion of the term that is used to refer even to artistic or literary works criticized for being too long and not too interesting. But the bubble of residential construction and the ensuing destruction of the environment has stopped suddenly as a consequence of the financial crisis that began in the summer of 2007, triggered by the American subprime mortgages and extended to the whole banking system through opaque risk distribution methods that neither rating agencies nor supervisors were able to control, with the result of a real estate crisis that has not been able to ‘unbrick’ the landscape, but that indeed creates unemployment and halts economic growth.

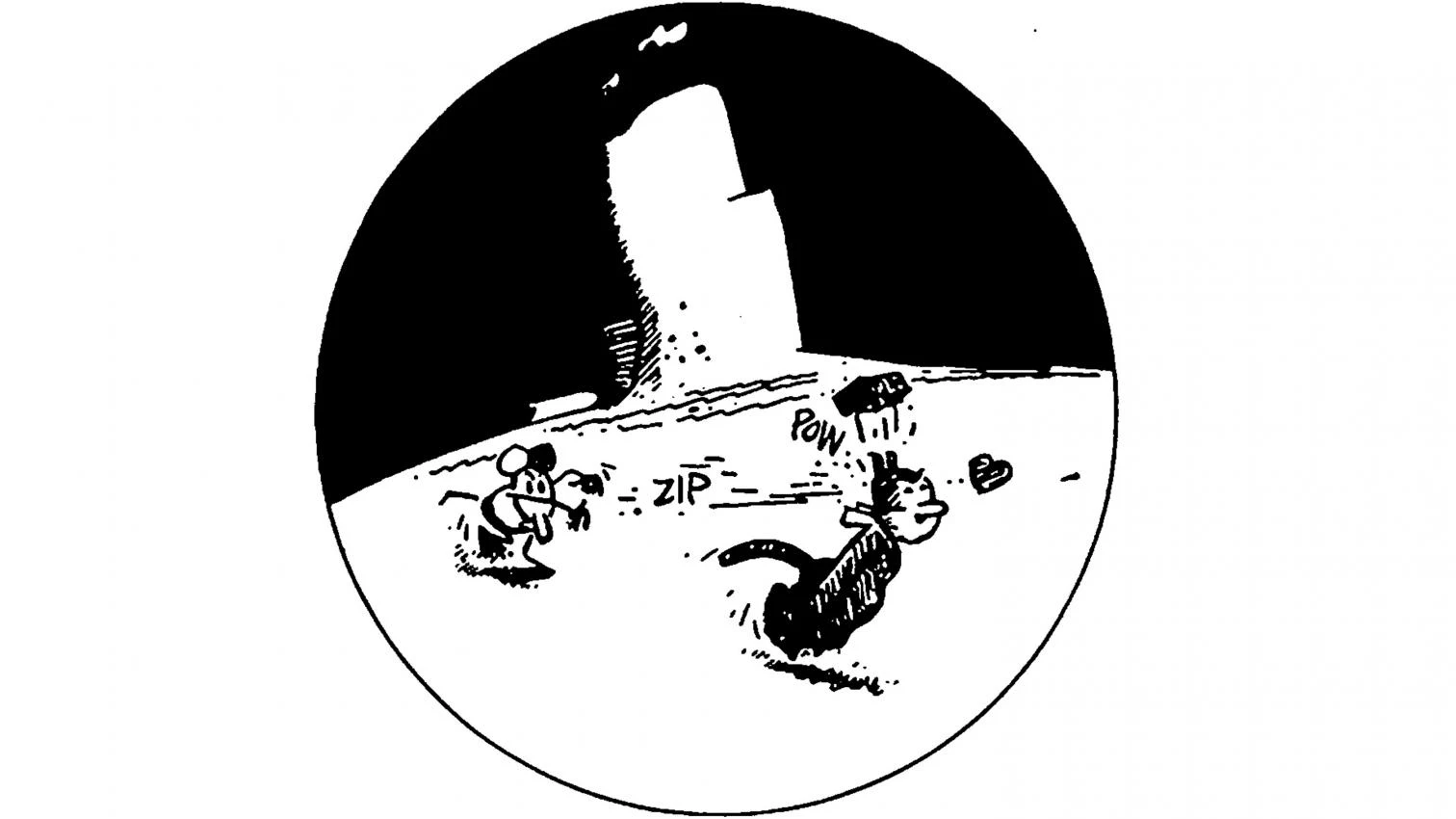

Even so, architecture has a timeless relationship with brick that neither modern neglect nor the current loss brick that neither modern neglect nor the current loss of prestige can ever break: the romance with ceramic will survive both in its most archaic and essential aspect and in the new uses of this eternal material, which turn craftsmanship into sophistication and modesty into luxury, reinventing brick for the 21st century. Architects shall continue to use brick in their journey to the origins and in their exploration of the future, but in this bond there will always be an element of self-inflicted pain. As the candid Krazy Kat knows well, a brick is a love declaration, and architects pursue beauty brick in hand; but the determination of Ignatz Mouse always stumbles upon the authority of Offissa Pupp, and the ‘bricked’ society points accusingly at the lovesick brick-thrower.