Peter Zumthor lives in a valley, and his scare but exquisite oeuvre has the slow pace, solidity and certainty of the vernacular. A cabinet maker before he became an architect, his buildings profess a stubborn devotion to artisanal perfection, and in their gravely sensual details resides an ancient and demanding god. Possessed by a passion for material, he invites his disciples to train in the discipline of this archaic craft by fabricating prisms of a single substance, and in these blocks of glass, dry leaves or slate throbs the same emotive pulse that beats in the master’s flakes of wood or stratigraphies of stone. The roughened face and white beard, which make him seem older than his 55 years, also give his figure a serene, kind and remote distinction. Zumthor delightfully points out the phonetic closeness of the words mother and matter, and one hears echoes of the hidden kinship that sustains a lifework nourished by material, place and memory.

From harboring a secret prestige, founded on works like the Chur archeological protection enclosure, Peter Zumthor has been pushed into the spotlight with buildings like the thermal baths in Vals.

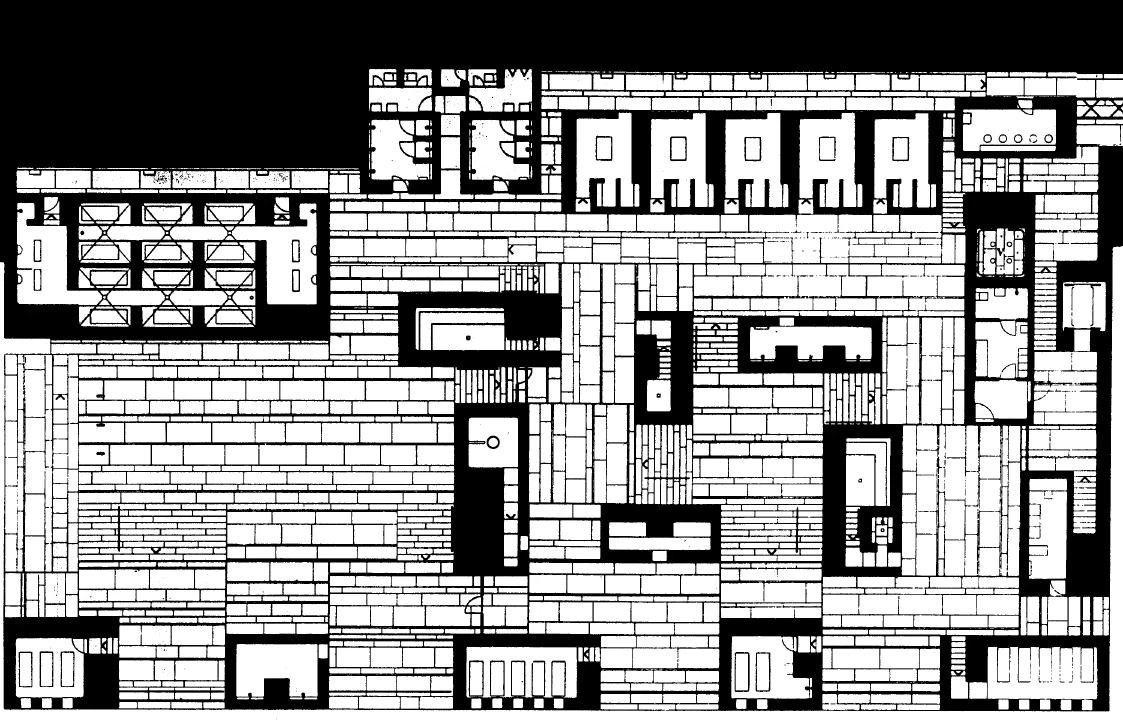

After his training in arts and crafts and his architectural studies in Basel and New York, Zumthor worked for a decade in the Heritage Department of the canton of Graubünden; not until 1979 did he set up a practice. But his first fruits made him an immediate cult figure. Three miniscule wooden works finished during the eighties – a tiny box of slats and skylights to shelter an archaeological dig; his own studio, an austere wooden striplined shed; and a mysterious, hermetic boat-shaped chapel which amid fog evoked an oneiric, frozen and primordial landscape – sealed a secret prestige that would become public in the nineties with the publication of his dwellings for senior citizens in Chur, a rigorous hunk of glass and volcanic rock, and overwhelming thereafter with the culmination of his two masterpieces: the thermal baths of Vals, an underground labyrinth of stone slabs, geometry and water in a deep Alpine valley; and the Kunsthaus of Bregenz, a concrete cube clad with flakes of glass containing an art center on the banks of Lake Constance.

In a short period of time, Zumthor’s grave and tactile architecture has passed from whisper to spectacle. But the timeless qualities of these buildings of interminable gestation and maniacal precision will undoubtedly survive the stubborn wear of the media. Nurtured by the writings of Peter Handke and John Berger as much as by the works of Edward Hopper and Joseph Beuys, the intimate, implacable architecture of this Swiss shows a minimalist, essential humanism that saves it from the fluctuations of taste. “To build houses like Kaurismäki makes films – that’s what I would like to do”, has said Zumthor, and indeed, his buildings possess the same desolate poetry, the same compassion, the same dignity and the same laconism as the films of the Finnish director. This wise, inexorable and gentle architect, who builds with lyrical violence remembering the objects and landscapes of his childhood, left his valley for a court to receive, from the hands of a queen, a prize and a treasure.