Democracy’s Appearances

The architectural forms of democracy started to blur with the commission of the projects for the extensions of the Congress and Senate buildings.

With a new chamber and office building, the Senate extension designed by Salvador Gayarre radically transformed the convent which since 1814 had been the original headquarters of the Spanish Parliament.

A democracy must keep up appearances. From the rites of protocol to the details of its architecture, the ceremonies and venues of popular sovereignty have to convey the dignity of its representational nature. In Spain, however, both the functioning and the urban presence of state assemblies are prone to sloppiness. The legislators we elect at the polls on June 6 would do well to learn the importance of maintaining outward forms.

Such forms have not turned lax in the course of an aggressive and ambiguous electoral campaign, nor did they ever slacken in the routine of a parliamentary life characterized by apathy and absenteeism. Democracy’s appearances began to fade when, in the mid-eighties, commissions were dealt out to enlarge Congress and the Senate. The respective extensions - fragmented and looking more like corporate headquarters than representative institutions - perfectly express how the majority of our deputies seem to contemplate our lawmaking chambers: as comfortable executive offices in which to domicile party politics.

The fact is that in legislative elections we do not elect legislators. We manifest our political preferences, back presidential aspirants, and grant a hundred citizens or so the chance to continue working for the parties that have designated them, enjoy a public salary, and benefit from certain privileges that go with the legislative function they hardly even carry out. The Congress and Senate extensions give architectural expression to the functionary, administrative character of Spanish democracy’s elected politicians.

Originally both Congress and Senate were accommodated in old convents. The then unicameral Cortes, which approved the Constitution of 1812, moved to Madrid two years after that and began to hold its deliberations in the church of the Convent of the Augustinian Fathers. After diverse political interruptions and very notable architectural modifications - the most important one by Aníbal Álvarez Bouquel in 1845 - this ecclesiastical premise has come down to our days as the Senate Palace. And Congress, which has its origins in the bicameral Cortes that were set up in 1834, assembled in the Convent of the Holy Spirit from that year until 1841, when it was decided that a new building be erected on the same parcel of Carrera de San Jerónimo: the current Congress of Deputies, which the architect Narciso Pascual y Colomer completed in 1850.

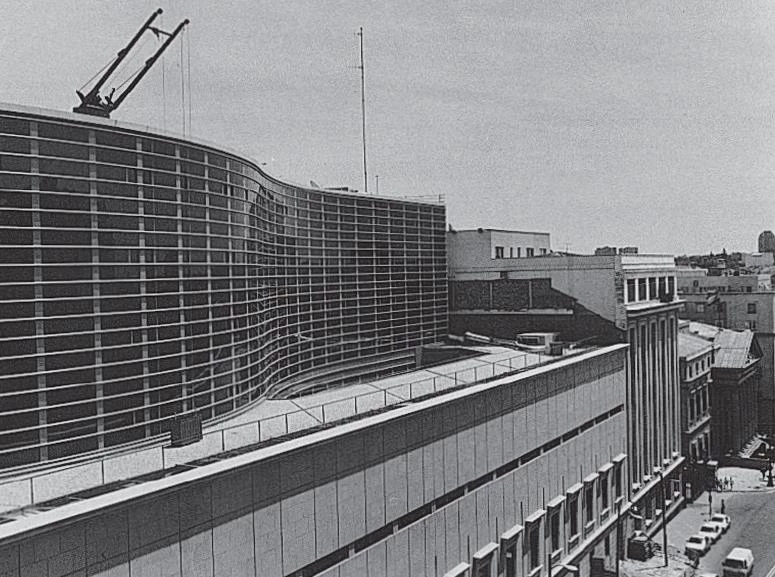

The team of Rubert, Parcerisa and Clos won the 1986 competition to expand the Congress, with a wavy curtain-wall and a low volume which is characterized by its ironic Venturian use of the classical palace window.

Thus, the contemporary extensions of Congress and the Senate are the most significant interventions on both buildings since the reign of Isabel II, when the primitive convents were either substituted (in the case of Congress) or substantially altered (in the case of the Senate) to give rise to the parliamentary chambers we know today. Neither the reforms undertaken in the latter during the second half of the 19th century - barring certain admirable pieces like the neo-Gothic library built by Rodríguez Ayuso in one of the cloisters - nor the unfortunate predemocratic annex to Congress, which connects to the old building via a bridge over Calle Florida blanca, measure up to the extensions of the past decade.

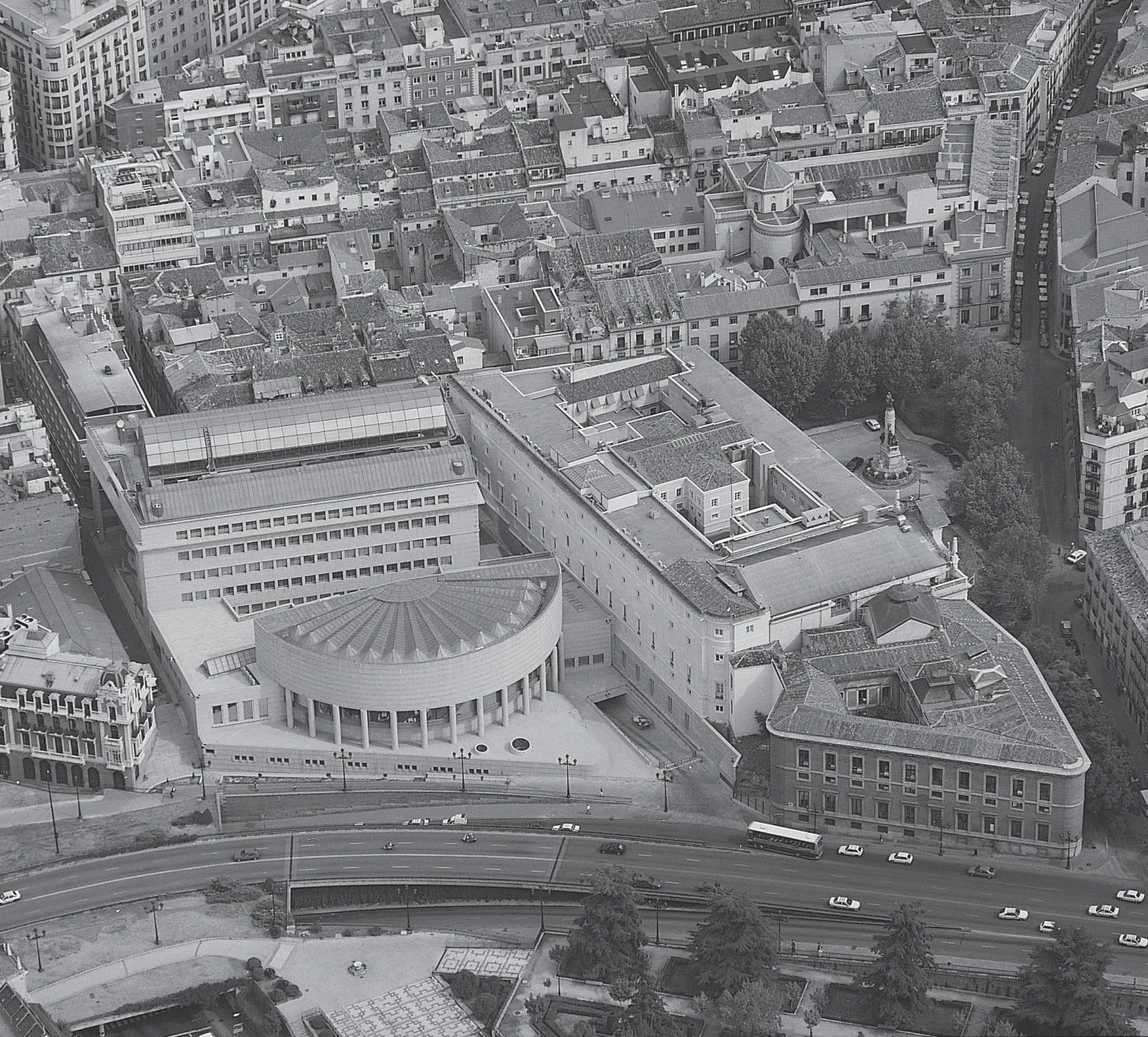

The Senate appointed its architect-conservator, the ill-fated Salvador Gayarre, who passed away last year, to build a new chamber with parking and offices. Clad with light pinkish stone in horizontal bands, the different volumes discreetly blend into the western cornice of Madrid, the city’s most characteristic view. The cylindrical chamber juts out into Calle Bailén, breaking the continuity of facades on a fast-traffic thoroughfare already distorted by a nearby overpass, and the offices are arranged inside a prismatic volume around a central covered court - an ‘atrium’ in the American style, which the author previously used for the central headquarters of IBM in Madrid.

Congress, in turn, is expanding in the form of an adjacent building that is to contain offices, ancillary parliamentary facilities and a new multi-purpose hall, having set aside - for the simple reason that it was physically impossible - the idea of another chamber on the narrow triangular lot that is the site of the enlargement. The work of a team of young Catalan architect-urbanists named María Rubert de Ventós, Josep Parcerisa and Oriol Clos, which won the competition held in 1986, the building comprises a low, sober, opaque volume attached to the extension that was carried out in the sixties, and which is adorned - more out of routine than out of irony - with a reiteration of the old parliament’s classical windows; and a slender office block whose glass curtain wall curves toward Carrera de San Jerónimo and forms a sharp edge nine stories high on the corner of Calle Cedaceros.

Both buildings have had problems with their neighbors, and we cannot say that the Cortes have been courteous to the city that so generously accommodates them. For the Congress extension to be executed it was necessary to demolish an entire city-block of officially protected buildings, bringing on the first amendment to the then recently approved General Plan of Madrid, certainly not a wise precedent to effect. As for the extension of the Senate, which has provided its members with a large garage for 250 cars, it has maintained the legislator’s abusive occupation of the Plaza de la Marina Española, and prohibited parking around, with a nonchalance typical of institutions that like to solve their security problems by appropriating what belongs to the citizens.

The Congress was built on the site of the former Convent of the Holy Spirit, its latest extension involving the demolition of a full block of protected buildings, forcing modifications in the General Plan of Madrid.

In contrast to this voracious parliamentary metastasis, life inside their walls continues with the same sleepy pace and the occasional conspiracies that surely came to pass in the convents whose grounds they occupy. The cells are now offices, and the churches, plenary session halls, but the cloistered endogamy of politicians contemplating the street through the tinted bullet-proof glass of their offices is the same as the narcotic encapsulation of functionaries and friars. The Thespian talents of political professionals are a thing of the past. The works they enact are short of roles, and do not even require the united support of a tuned choir: we make do with prima donnas and the electronic sets of television studios. In the church or the legislative chamber, one prays, turns the voting key, reads breviaries or newspapers, falls asleep.

The scant enthusiasm of our lawmakers makes it easier to understand the unwillingness of architects to sanctify parliamentary life. The postmodern, contextual and mannerist language of both extensions comes, without a doubt, from the cynical conformist intellectual climate of the eighties, with its playful evocation of classicism, its rejection of transcendence, and its flight from emphatic expressions. But it is also the result of the absence of passion, formal carelessness and the routine of the buildings’ users. They are toned-down replicas, of the architecture of mature James Stirling in the case of the Senate, and of the language of Robert Venturi’s National Gallery in that of Congress. But they are also a clear reflection of the lack of conviction that governs Spain’s contemporary legislature, which has recuperated a venerable institution just when the media and the society of spectacle have entirely deprived it of meaning, turning it into a resounding hollow shell.

Two years ago now, in September 1991, the king inaugurated the newbuilding of a Senate that claims to be a representative assembly of the Spanish regions; neither Jordi Pujol nor José Antonio Ardanza nor Manuel Fraga, the presidents of the three historical regions – Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia – bothered to attend. Presumably the next parliamentary session will begin with the official opening of the new building of Congress, which will then only have the reform of the old extension to complete. It will be interesting to see how many political agendas manage to make space for this ceremony. After all, it would be an unexpected paradox that the occupants of parliamentary venues should be the least believing in their virtues, that these urban convents should be inhabited by unbelieving monks. Still, this voter would be grateful if they were to keep up appearances.