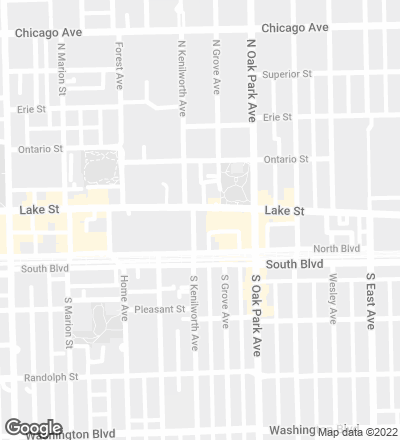

Unity Temple, Oak Park

Frank Lloyd Wright- Type Religious / Memorial Place of worship

- Material Concrete

- Date 1905 - 1908

- City Oak Park (Illinnois)

- Country United States

- Photograph Thomas H. Heinz Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Within the interpretation of his own genius as demiurge of his time, Wright created his own formula to deal with religión, a mixture of Laotse with a philosophical and practical Protestant Christianism, an intelectual and aesthetic option rather than a profound one. The interest of the architect for Japanese art – discovered in the Chicago exhibition of 1893 – added to this formula the features of graphic quality and spatial unity. The project for the Unity Temple – located in the same neighborhood where he built some of his client's houses – gives him a great opportunity, after the project for the Larkin offices, to think about religious buildings at once from a double point of view: public, as a small collective place; and domestic, as a large family room.

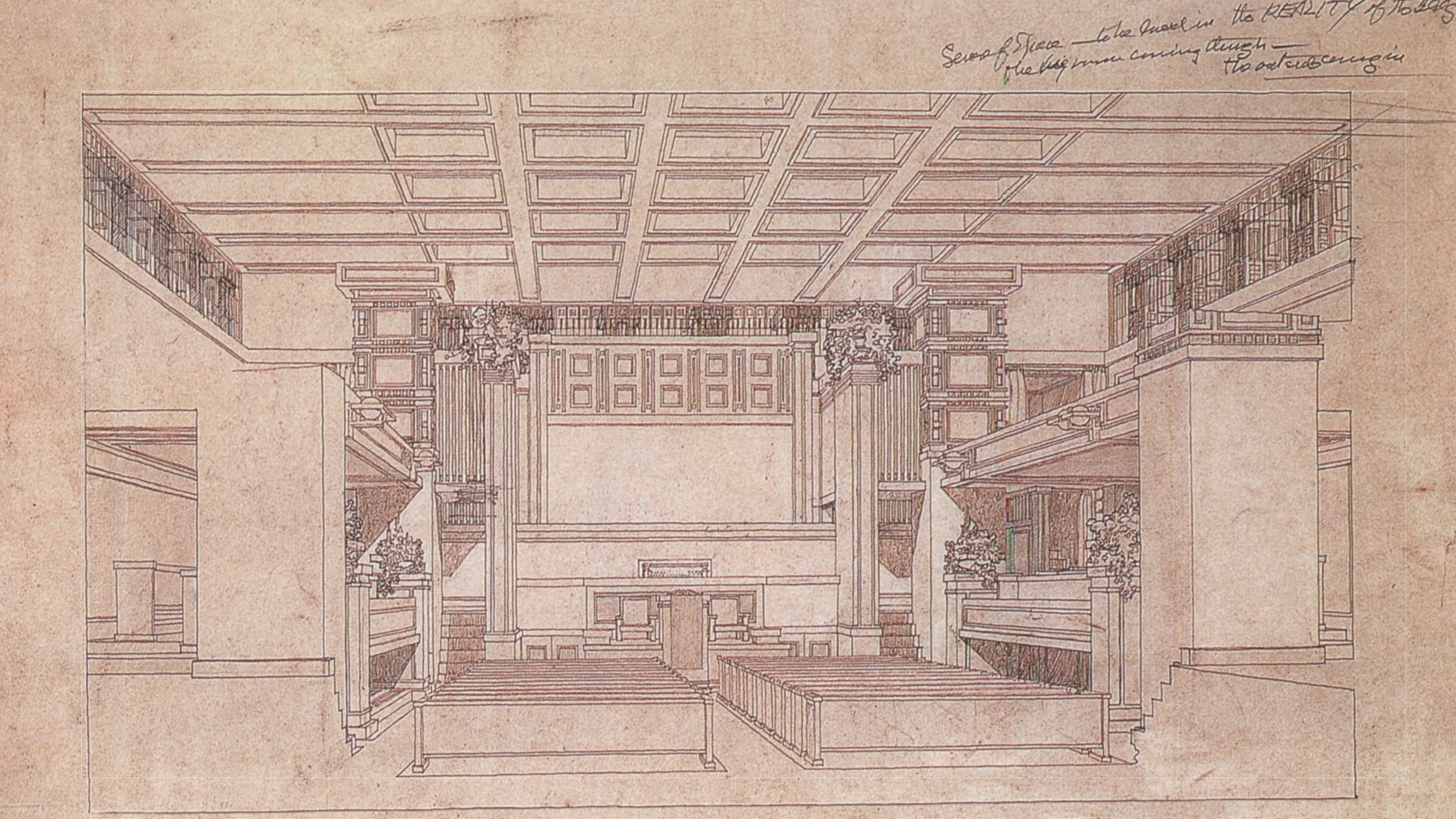

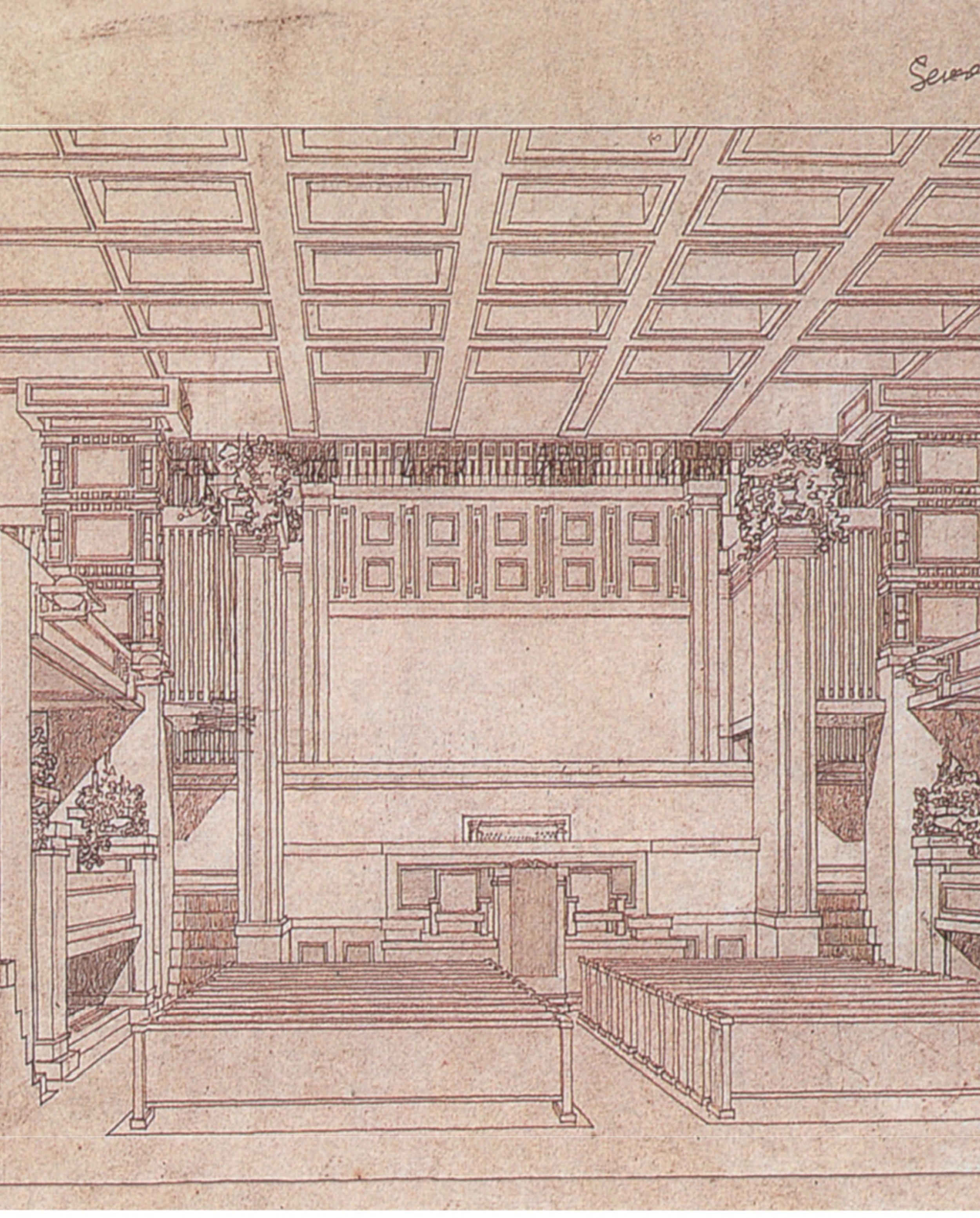

Wright himself acknowledged having confirmed in the temple his perception of space as a significant unit, which he foresaw in the Larkin building. In fact, the church appears to be a perfect space in the configuration of consecutive concrete planes that enclose a single ambit. It is a space for words, resembling a small a uditorium and a synagogue, with surrounding alcoves and skylights as a squared and concentric livingroom with an clear center, where the speaker’s platform and organ play the role of the chimney in his domestic projects. The lienar decoration, with mouldings fractured in straight angles, unifies the surfaces and furniture accentuating the articulation of the architecture’s straight plans with a grid of wooden strips, as if the edges of construction were not enough. The slender geometry common to Wright’s houses replaces any symbol of trascendence or allusion to religious feeling. And the same happens in the exterior; the folded walls, molded and painted in pastel colors contrast with the closed, monumental, and monolithic exterior, as if merged into one single piece of concrete, and upon which the austere decoration of geometric friezes makes reference to a discreet luxury. This is a public, civil and horizontal building, a relative of the Viennese Sezession that speaks louder than any of its Austrian cousins.

The layout of the church, following that Larkin’s offices, initiates an articulate and hierarchical way of designing, with the secondary elements arranged orderly around the principal space; something that Louis Kahn would later recover in a masterly interpretation. It is, in sum, a secular Mandala plan, referred to its central symmetry and, despite not having a symbolic purpose, it expresses with aesthetic intensity a desire of perfection...[+][+]

Opening

Central skylight seen from below.

Photos

Paul Rocheleau.