Zigzag Zaha

El premio Pritzker 2004 ha distinguido a Zaha Hadid, la iraquí afincada en Londres cuyo lenguaje diagonal o sinuoso es tan singular como su figura.

More an artist than an architect, and more a personality than an artist, Zaha Hadid is the rotund embodiment of the diva. Temperamental, overwhelming, her voluminous figure wrapped in pleated Issey Miyake tunics is a physical presence irradiating aplomb and contained energy. On impossible shoes and decked with breathtaking jewels and bags, the London-based Iraqi transmits the self-confidence of one who has built her image as determinedly as her work. Since the old days when she dressed herself up in innumerable gauzes painstakingly held together with dozens of safety pins, Zaha – as she is widely known – has made of her person an artistic project that is as significant as that which consists of her paintings, drawings, stage sets, and designs: a road previously explored by Dalí, Warhol, or Beuys, but less commonly in the professional world of architecture.

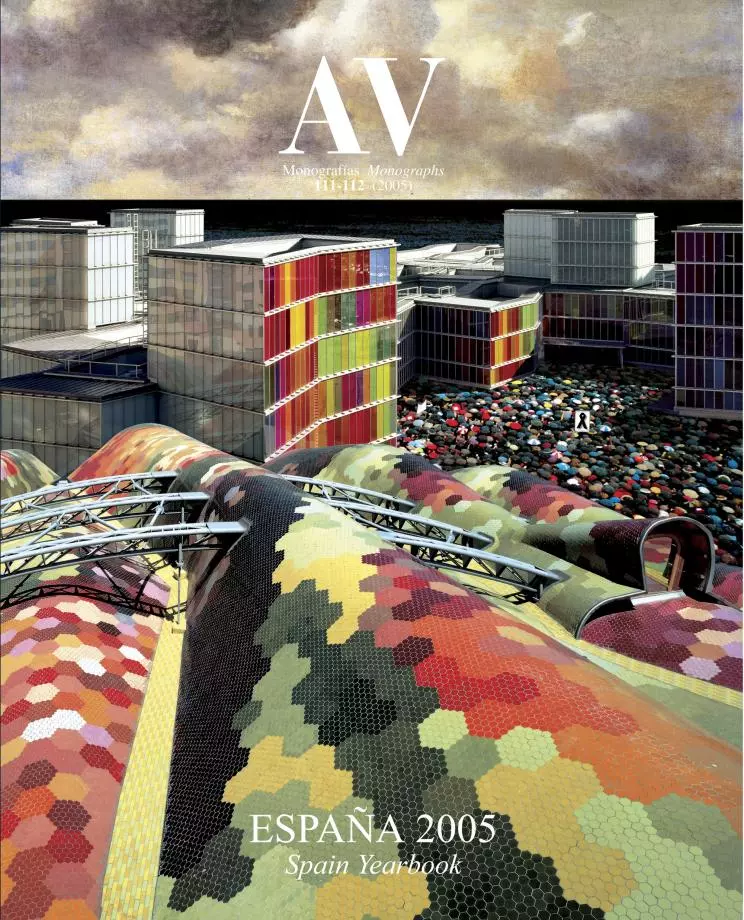

Elevated to the status of a media icon, last year she received the European Union Mies van der Rohe Award for a zigzagging concrete canopy over an intermodal terminal in Strasbourg that she was commissioned to build as an invited artist, and this year she wins the Pritzker Prize for a career where visionary representations outnumber actual built works. None of this diminishes the merit of the awardee or makes her victory polemic: unanimous recognition of her sculptural talent made Zaha, “ironically, a sure option” in the Mies, said jury president David Chipperfield; and her being a woman and of Arab origin, along with her popularity among students, which was highlighted among the motivations of the Pritzker jury, turned the architect into as politically irreproachable a candidate as befits the American prize (however much its going to “Zaha Hadid from Great Britain”, at a time when there are still British troops in Irak, lends itself to other symbolic readings).

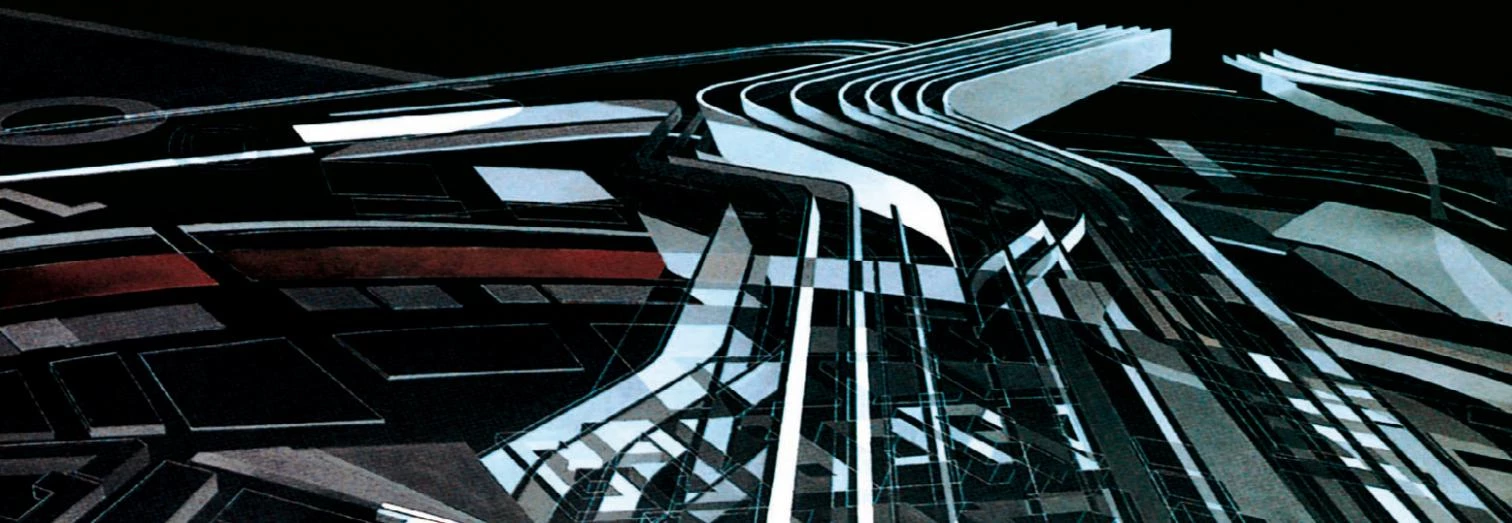

From the oblique columns of Strasbourg to the flowing forms of the Contemporary Arts Center project in Rome, Zaha turns the zigzag into a distinctive feature, as abridged in the sketch for Cincinnati.

This year, in place of the late J. Carter Brown and Giovanni Agnelli, the Pritzker jury counted two new members: Rolf Fehlbaum, president of Vitra, manufacturer of signature furniture and promoter of avant-garde architectures and, as such, Zaha’s first client; and Karen Stein, editor of Phaidon in New York. Both names add weight to design and the media in the prize, giving importance to publicity and image, in tune with the spirit of the times, and thereby making the jury’s decision more readily intelligible. For thirteen consecutive years now the Pritzker has stayed clear of American architecture, prolonging the absence in the hall of fame of Peter Eisenman, an author for whom professional recognition has been hindered by his experimental and critical inclinations. With Koolhaas’ winning the prize in 2000 and Zaha’s capping it now, however, the delay of Eisenman’s Pritzker can only be attributed to some stubborn animadversion.

Endorsed by a trophy of such significance and inundated with projects, it is now that the real career of Zaha takes off. Appropriately, the architect is to receive a medal in St. Petersburg, in the same Russia where, from El Lissitzky to Malevich, many of the constructivist and suprematist experiments that nourished her London training were initiated, not to mention the canvases of Liubov Popova, whose translucent geometric forms, derived from analytical cubism, are prolonged in Zaha’s ‘X-ray drawings’. The author of crystallographic landscapes and fractured topographies who urged the engineer Peter Rice to make everything at an angle now proposes spaces that flow over and penetrate territories of methacrylate, replacing acute angles with curves, zigzags with spaghetti, and collisions with fluxes. She will continue to make concrete float, tangle up ramps, or orchestrate sheaves of slender columns diagonal like the rain. But her aesthetic vocabulary will from now on be at the service of a determination to build a liquid architecture.