Leaves of March

April will bring the Pritzker and Mies awards; in the calendar of the previous month, the death of Ignasi de Solà-Morales looms over the hassle of the prizes.

Thurday the 8th. In Nantes with the jury of the Mies van der Rohe Award, after a journey made eventful by airlines’labour conflicts. The visit to Nouvel’s Palace of Justice is disappointing. We recently put it on the cover of Arquitectura Viva and its dark, obsessive geometry had promised a reflecting, frozen perfection. But the monumental and scenographic regularity of its interior of black lights, which I was ready to take as a severe emblem of the rigor of justice, manifests a stiffness that is closer to the maniatic modularity of Ungers than to the painstaking exactitude of the Mies who built the Neue Nationalgalerie, with which it has inevitably been compared. The claustrophobic courtrooms, the labyrinth of offices, and the schematic composition of the portico do not speak of dura lex, but of fiat iustitia et pereat mundus.

Friday the 9th. The tour of Mies finalists continues, bringing us to northern Spain to see Juan Navarro Baldeweg’s Altamira museum and Rafael Moneo’s Kursaal. Several of the jury members are here for the first time, so the organizers try to insert other musts in the itinerary: Santillana village and the Guggenheim museum, Casa Calvo and chef Arzak’s restaurant. The replica of the caves and the adjoining museum have the ambiguous charm of a facsimile and the silent elegance of a building that defers to the landscape. But in the collage of mate-rials, textures, and colors that make the excavated construction blend in withthe bucolicsurroundings, some see only a painter’s work, specifically one indebted to the lyrical mannerism of the latest Siza in his luminous interiors, carefully watercolored with strokes of tender green, mustard, and cinnamon on the skin spread over the moist hill.

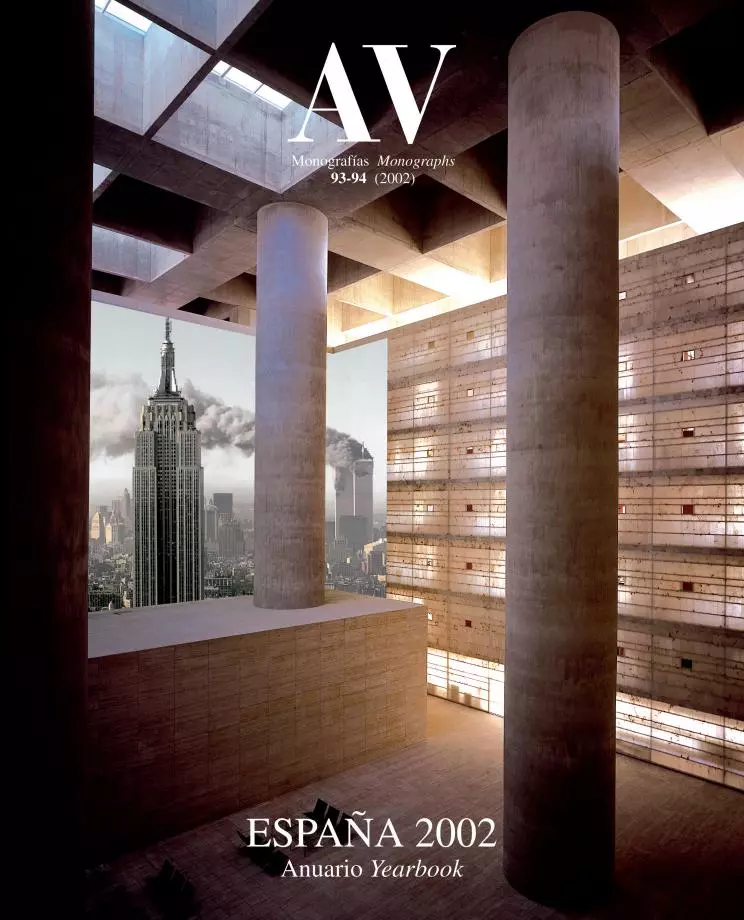

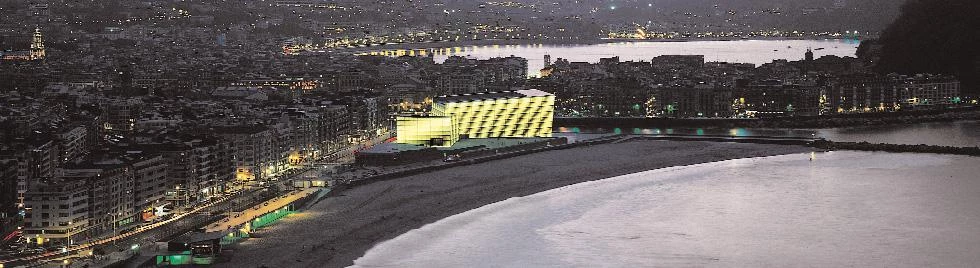

The dark geometry of the Palace of Justice in Nantes and the landscaping skill of Altamira Museum competed this year for the Mies van der Rohe Award, which finally went to the luminous cubes of the San Sebastian Kursaal.

Saturday the 10th. The delicate violence of the Kursaal by night vanishes in the morning. The huge slanting prisms, which gleam in the dark like drunk-en lanterns, maintain their Japanese rice paper weightlessness in daylight, but the orangey amber glimmer gives way to a milky shine and the build-ing is a blurred profile against the overcast sky. In-side, the imprecision of construction surprises sev-eral in the jury. I am more struck by the tension of the security measures, the impatient guards, the dogs sniffing the auditorium seats in search of bombs.Yesterday an ertzaina was killed, tainting the first bars of the Basque Country’s electoral cam-paign with anxiety. A deplorable morality play of abertzale exaltation of rural life is being rehearsed on stage, and the contrast between technical means and dramatic incompetence leaves one perplexed. In the Kursaal art gallery, a fine Oteiza exhibition astounds us with that impossible combination of ex-quisite beauty and lunatic anthropology that leads the visitor from the apostles to the blackboards.Who said it was easy to be Basque?

Sunday the 11th. Last jury meeting in Copenhagen after visiting the Unibank headquarters, an office complex by Henning Larsen which was included in the final selection in order to compensate for the monopoly of public buildings. Its meticulous, trivial, corporate architecture provokes conflicting opinions. Lacking in the initial list for the European prize are Swiss works, winners of the previous Mies with Zumthor and firm candidates for the Pritzker with Herzog. This conspicuous Brussels-imposed absence is disturbing to many, who regret not being able to consider the Ricola offices, a critical point of inflection in the career of Herzog & de Meuron; the same team’s Tate Modern in London, a formidable public success; or Nouvel’s convention cen-ter in Lucerne, a happy work of a great architect who has so far been ignored by prizes. The debate heats up. Dominique Perrault gets the opportunity to show his southern temperament, Wiel Arets his amiable ambiguity, David Chipperfield his tranquil equanimity, and Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani his conciliatory disposition. It is necessary to postpone judgment and cancel tomorrow’s press conference in Rotterdam. In any case I had already decided not to attend, when Rem Koolhaas put off our appointment there, so back to Madrid I go, in time to visit my father, recovering from a fracture of the femur and the complications of his eighty years.

Monday the 12th. Grading of students’ final projects with Juan Navarro Baldeweg, Alberto Campo, José Ignacio Linazasoro, and Gabriel Ruiz Cabrero. The school dean, Juan Miguel Hernández León, receives a call from Barcelona: Ignasi de Solà-Morales has died of a stroke in an Amsterdam hotel. He was 52, and this very morning he was scheduled to meet with Lluís Hortet and Diane Gray in Rotterdam, to participate in the public announcement of the winners of the Mies Award. He had sat on the jury on numerous occasions, and the offices of the Mies Foundation, the Barcelona pavilion, was reconstructed by him from 1982 on. That was the year we first met, after inviting him to participate in a seminar in Toledo of Menéndez Pelayo International University, organized with Antonio Fernández Alba, and thereafter we maintained a cordial, intermittent relationship threaded by editorial and academic collaborations, including a joint consultancy for the architecture line of Gustavo Gili publishers at the threshold of the nineties, which gave occasion for frequent Barcelona lunches. Still unbelieving, I make a perplexed and melancholic run-through of our encounters over the years. Peter Eisenman, an old friend of Ignasi, takes my phone call with consternation.

Tuesday the 13th. Changes surrounding the competition for Córdoba’s Congress Center, which we are helping to organize. Koolhaas will be coming in April whereas Nouvel has withdrawn. I will try to dissuade him but chances are slight.This madness of mediatic architecture and superstar architects is dislocating everything and we critics are being pulled into the whirlwind. I keep thinking of Solà, trapped in the vertigo of architectural media after his reconstruction of the Liceo opera house. In the afternoon we listen to top graduating students present their final projects in a packed lecture hall and, as has become the norm, most are female.

Wednesday the 14th. Juan Navarro, Juan Miguel Hernández and I arrange to meet in the Madrid-Barcelona air shuttle, and at the Les Corts morgue we come across other friends who have traveled for the funeral: Víctor Pérez Escolano, Carlos Sambricio, and Rafael Moneo, who was very close to the Solàs through Ignasi’s brother Manuel. Most of the Catalans there I have not seen since Enric Miralles’ burial, and I find this disquieting. Juan Navarro, who also was at the Igualada cemetery, attributes the ominous coincidence to the statistical regularity of risk that corresponds to our age, a hardly comforting actuarial reflection. But I always find it calming to converse with him and on our return together the sad evocation of our deceased friend gives way to the recollection of the amiable Alicante spots shared with Ángel González. Back in Madrid I get a phone call from Oscar Tusquets, whom I missed in this morning’s service. He tells me about his prize and Gino Valle’s replacing Robert Venturi as the one-person jury, and I am not able to conceal a worn out skepticism.

The awarding ceremony is held in the Barcelona pavilion of Mies. Ignasi de Solà-Morales, author of the reconstruction of the building and linked to the prize since its creation, passed away suddenly shortly before the decision.

Thursday the 15th. My sister the doctor wakes me up very early. Our father has had to be rehospitalized. In a few minutes I am in Moncloa clinic but the emergency has passed. I stay all morning, watching him succumb to fatigue or simply chatting trivialities. Because the clinic looks out to the street Aniceto Marinas, my father recalls the sculptor’s high reliefs in the stairway that connects Teruel’s train station to the Plaza del Óvalo, inevitably dedicated to the theme of the Amantes, but soon memory dilutes into incoherent fragments. After lunch I speak with Carlos Jiménez, my Houston friend who will be a judge in this year’s Pritzker, and we make plans to meet up on the occasion of the awarding ceremony to be held in Monticello, the mansion of Thomas Jefferson which introduced neoclassicism in the United States. What seems to be an indirect tribute to an architect president now reviled by the new American Right is an additional stimulus to attend. Late in the afternoon Jacques Herzog phones to apologize for declining an invitation to sit on the jury of the Córdoba competition, and to tell me how his Barcelona and Santa Cruz de Tenerife projects are developing. He wants us to meet in Basel or Madrid, but we both know he will be extremely busy in the coming months. In this calendar of eves, pain casts its slender shadow on the hustle and bustle of awards in order to compose a light vanitas, and the ides of March end with a taste of ash.