Viennas Stables of Art

The old imperial stables have been tranformed into the new Museums Quartier, a large cultural complex which includes the Leopold and Ludwig collections.

Genius and Austria do not go together, says Thomas Bernhard, and the complex of muse-ums that has been raised in the interior grounds of Fischer von Erlach’s imperial stables confirms the pessimistic opinion of the author of Old Masters. Along with the Kunsthistorisches Museum, which the main character of Bernhard’s story visits with obsessive regularity in order to meditate in front of aTintoretto, the architects Manfred and Laurids Or-tner have erected several art venues whose pris-matic volumes are concealed in the huge courtyard of the stables, a Baroque building that has been simultaneously refurbished by Manfred Wedhorn for auxiliary cultural uses. Opening during the summer, beginning with theArchitektur Zentrum and the Kunsthalle in June and ending with the Ludwig Foundation and theLeopold Collection in September, the complex is compared by its promoters to Washington’s Mall and Berlin’s Museuminsel, and they stress that the 60,000 square meters of this Viennese art quarter puts it among the world’s ten largest. Such a naive point indicates both the so-lidity and the triviality of the endeavor.

Fischer von Erlach’s imperial stables become a museum complex with the addition of the limestone cube and the basalt block of the Leopold and the Ludwig collections, as well as the long block in brick of the Kunsthalle.

Ortner & Ortner are certainly not geniuses, but these two architects born in Linz in 1941 and 1943, respectively, have a solid track record of artistic creation, working during more than two decades from Düsseldorf as Haus-Rucker-Co, a name they shared with Günter Zamp Kelp.The commencement of their independent career coincided, in 1987, with the announcement of the competition for the Viennese stables, so their victory there marked the true begin-ning of their architectural biography, as well as the start of an endless battle to materialize their project without giving up more than the inevitable in the fainthearted, stilted context of the Austrian capital. Vienna is a cultural concept, Bernhard said, even though there has been virtually no culture in Vienna for a long time, where things have gone into an alarming decline also in the musical sphere, because nothing out of the ordinary is being offered either at the Konzerthaus or at the Musikverein. In this pale Vienna, the Ortners have built a precinct that hopes to attract more than a million visitors yearly, but of course the foreigners who come to the city are easily satisfied, Bernhard said.

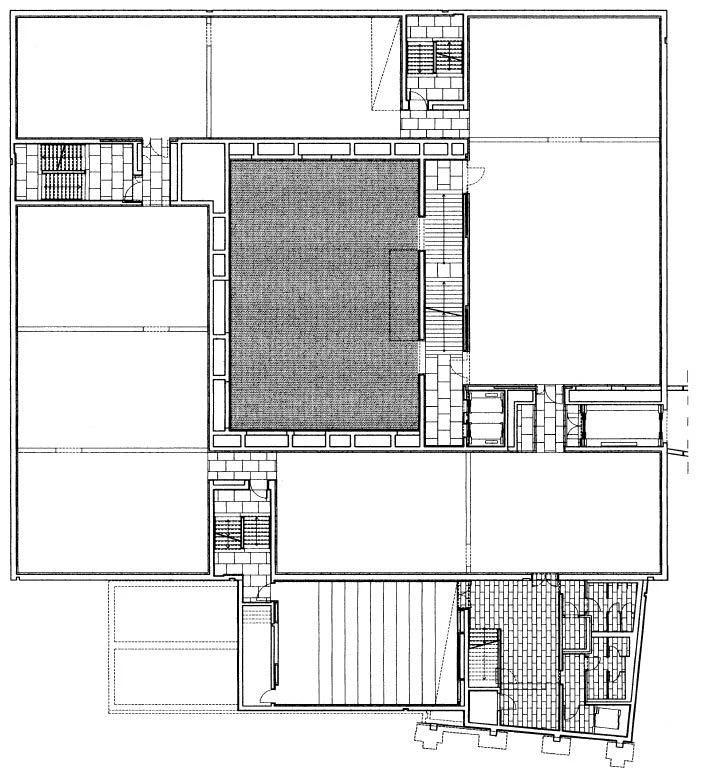

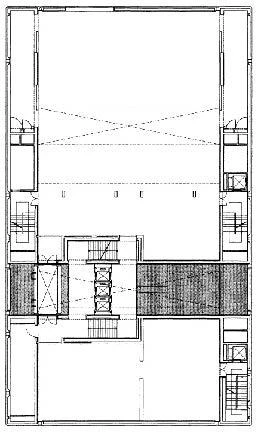

The Leopold Museum is a white prism that seems to emerge from the courtyard paving, and where the collection of Austrian art is housed in halls laid out in turbine around a monumental and naked top lit atrium.

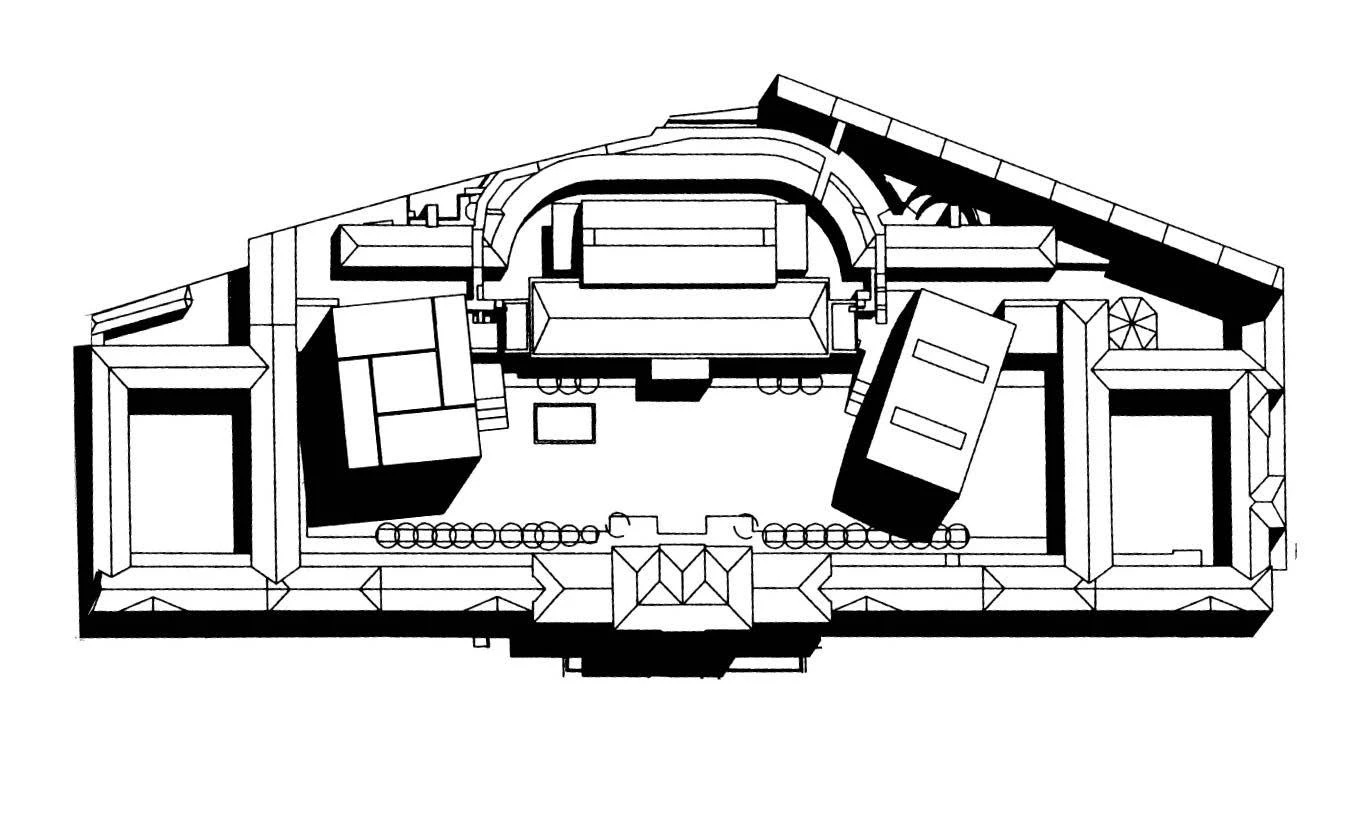

The project per se was nothing excellent, simply correct: several prismatic pieces placed at angle inside the large courtyard of the imperial stables, in the wake of Louis Kahn’s unbuilt Dominican convent of 1965, and of its postmodern reinterpretation in a building designed in 1979 and finished the same year as theViennese competition, the Berlin Science Center by James Stirling, the most prominent member of the jury that elected the Ortners. The revisions suffered by the first proposal before the start of construction work in 1998 made it necessary to reduce the height of the new volumes and delete the tower that would have stood in front of the facade. This eliminated the desired dialogue with Gottfried Semper’s two buildings, the Museum of Natural History and the Kunsthistorisches. But it also allowed a maturing of the language of the architects, who in a decade shifted from a conceptual Rossian historicism to a minimalist eclecticism in keeping with the conventional tastes of the times, and perhaps more in tune with the superficial Baroque eclecticism of Fischer von Erlach, an exact expression of what Bernhard called that dubious Habsburg taste in art, aesthetic and repulsive.

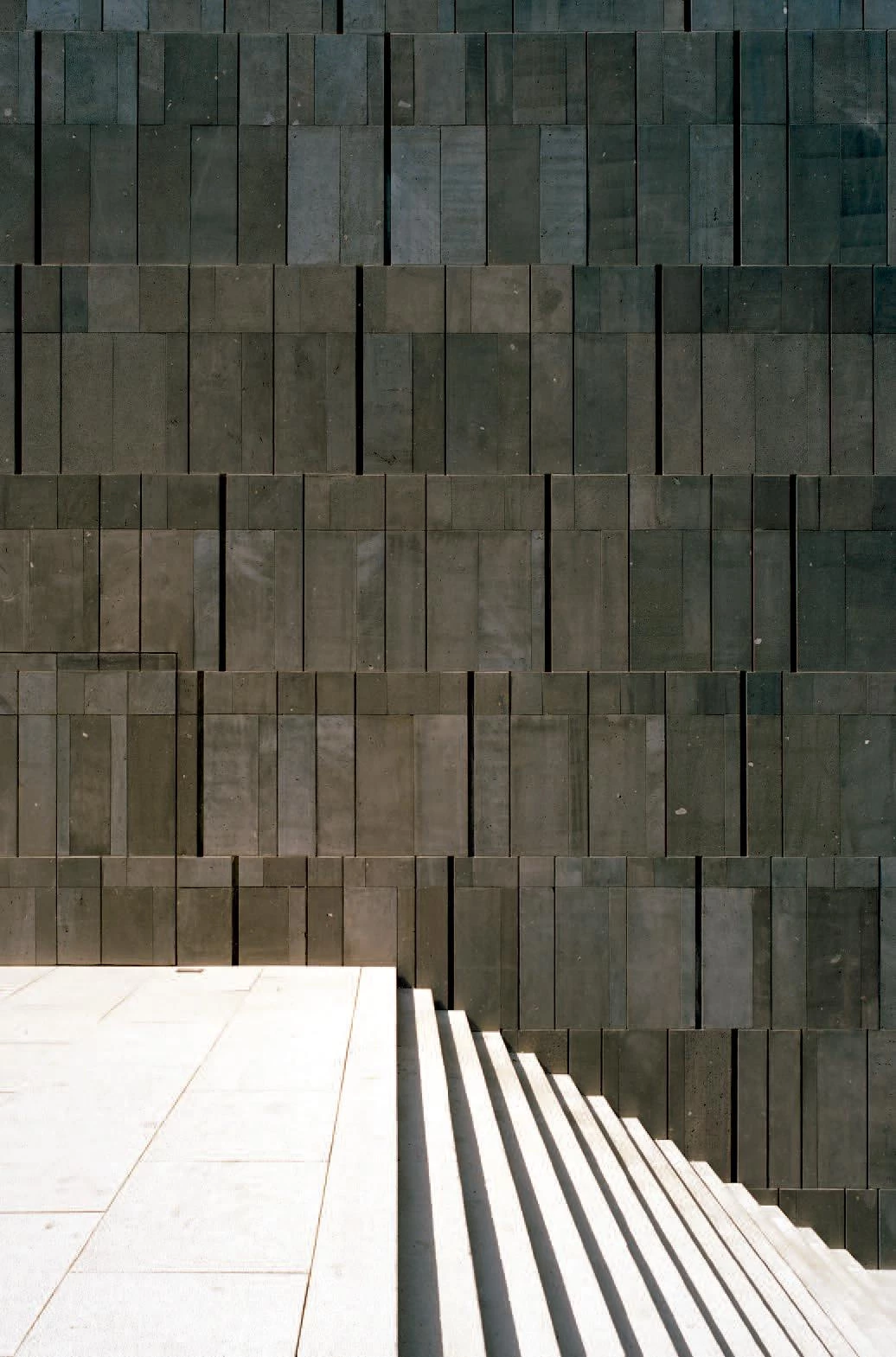

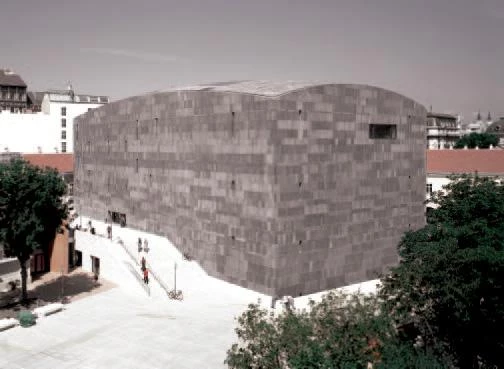

The Leopold Collection is accommodated in a cube clad in white sandstone and featuring oak-wood floorings and brass joineries. It is aligned with Semper in the distance, and its routinary modular geometry is not at a par with the core of the collection, consisting of works by Egon Schiele, who is not kitsch like Klimt but of course Schiele is not a really great painter either, Bernhard said. In its turn the Ludwig’s container is a hermetic block of gray anthracite basaltic lava with a curved roof, ceramic floorings, and interior finishes of smelt metal and glass. It is aligned with the layout of the residential quarter immediately surrounding it, and its monolithic rotundity is not inappropriate for the works on display inside: American pop and the hyperrealists, conceptual and minimal art, land art and art pòvera, but also Fluxus and Viennese actionism, not to mention that Austrian contemporary so cheap that it does not even deserve our blushes, Bernhard said, and which will also go on display in the Kunsthalle, a huge brick shed attached to the rear of the winter riding academy, like the two other buildings inside the stables courtyard.

As a dark counterpoint, basalt clads even the curved roof of the Ludwig Museum, whose narrow facade openings help to guide visitors through the two types of halls: small in the north front, and larger in the south one.

The complex, which because of the inevitable synergy brings together institutions as diverse as a tobacco museum and a children’s museum, along with the facilities of the Vienna festival and the Cen-ter of Contemporary Dance, and which naturally includes a generous share of restaurants, bars, information centers and shops, is open 24 hours a day, not only so that art historians can drive their helpless flocks by, as Bernhard said, but also to offer itself as a place of permanent leisure and entertainment, in recognition of the glaring fact that, in the end, people only go to the museum because they havee been told that a cultured person must go there, and not out of interest, people are not interested in art, at any rate ninetynine per cent of humanity has no interest whatever in art, Bernhard said.

The Vienna of Wagner and Loos is today a Vienna of chocolate, civilized and amiable. The gilded Vienna of the turn of the century and the red Vienna of the interwar period have given way to the pallid Vienna of pastry shops and routine where this museum quarter now rises, efficiently developed by a team that has paid attention to the graphic design of its corporate identity, surely better than that of the simultaneous monograph on the architects, presented in dictionary form and endowed with the dubious lure of fragments. But the two prismatic pieces lost in the courtyard of the stables are unsatisfactory in the end, their details hardly rescuable if we make an effort to observe them closely, as we then notice their insufficiencies and errors, perhaps because the human mind is a human mind only when it searches for the mistakes of humanity, Bernhard said. A great piece of architecture, he said, how quickly it is diminished under the scrutiny of an eye such as mine, no matter how famous it may be, and especially if it is famous it sooner or later shrinks to a ridiculous piece of architecture.