The Tired Goddess

The centenary of Lina Bo Bardi has rekindled the fervor for her figure. The critic Rowan Moore considers the Italian-Brazilian “the most underrated architect of the twentieth century”; however, she who Martin Filler describes as “the Anna Magnani of architecture” is now enjoying an extraordinary wave of acclaim through publications and exhibitions. Her death in 1992 gave rise to a monograph and exhibition, organized the following year by the Institute dedicated to her memory; but until the PhD thesis of Olivia de Oliveira in 2006 there is a parenthesis of silence that has been broken by the approach of her centenary, with the show in the Venice Biennale of 2010 curated by Kazuyo Sejima, the publication of her writings by the AA in 2012, the monograph by Zeuler R. Lima in 2013, and the Munich exhibition organized by Andres Lepik in 2014-2015, with a catalog featuring essays by prominent experts – all these initiatives throw light on the rich personality of a mythical figure.

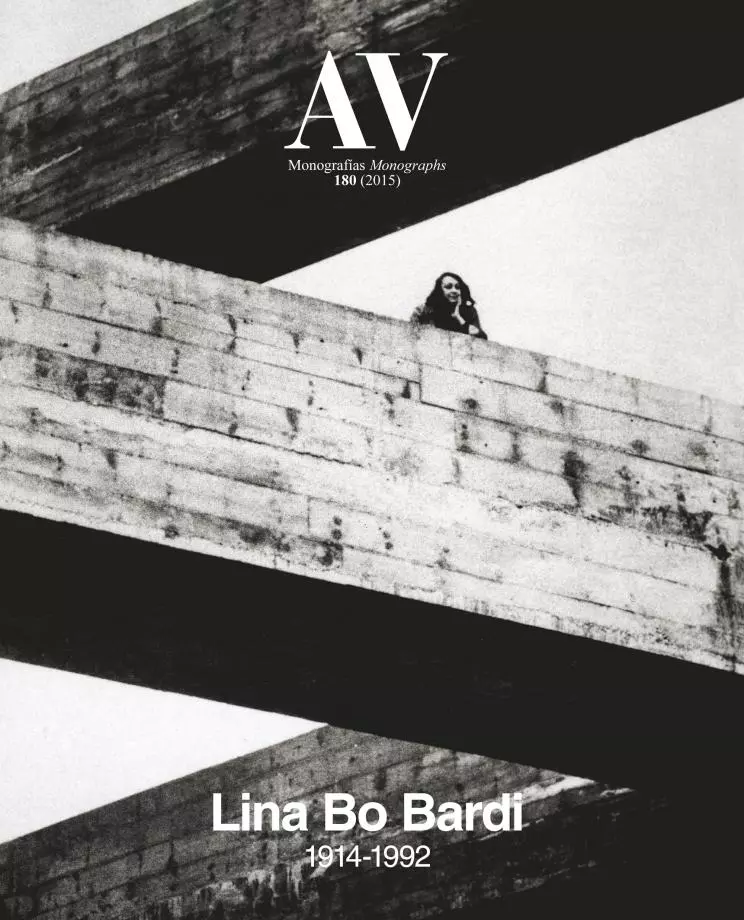

Her friend Valentino Bompiani called her ‘la dea stanca,’ but this ‘tired goddess’ described herself (on the occasion of her first exhibition, held in 1989 in São Paulo) as “Stalinist and anti-feminist,” honoring her political convictions and the fact that in Brazil she had never felt discriminated as a woman. Before settling there in 1946, Lina Bo had studied in Rome under traditionalist architects like Giovannoni and fascists like Piacentini, and after graduating in 1939 she was part of the Milan circle of Gio Ponti, the architect, designer, and Domus editor who at the time was close to Mussolini, as was her future husband, the journalist and dealer Pietro Maria Bardi, so her alignment with the Communist Party can only be explained by her radical independence. In Brazil this freedom distanced her from Costa and Niemeyer, criticizing Brasilia and choosing a creative path that openly deviated from the tropical modernity sanctioned by the MoMA in the 1943 show ‘Brazil Builds.’

Thus her Casa de Vidrio of 1951, closer to the Case Study Houses than to the canonical glass houses of Mies or Johnson, and whose added conventional wing has been compared by Barry Bergdoll to the hybrids of modern and vernacular of another expatriate in São Paulo, Bernard Rudofsky; thus her MASP of 1957-1968, in tune with Vilanova Artigas or the younger Mendes da Rocha, her most ‘Paulist’ work in its structural daring, revolutionary exhibition space, and generous creation of a public place; and thus finally her finest work, the SESC Pompéia of 1977-1986, an obsolete factory of dramatic industrial beauty, which she chose not to demolish, transforming its spaces into a civic center that fuses culture with everyday life. While the house, when visited, gives less than it promises, and the MASP exactly what one could hope for, the SESC experience is so fertile and moving as to surpass all expectations, and explains the present fascination with Achillina di Enrico Bo, whom the world by now knows simply as Lina.