History Accelerated

In a Europe that confirms its cohesion through the Maastricht Treaty, architecture devoted to communications and transport stands out.

The monotonous rhythm of the seasons and days hardly concurs with the beat of history, which either halts or quickens, like a heart asleep or gone wild. The fall of the wall initiated a period of uncertainty that augured cardiac arrhythmias, but nothing prepared us for the vertiginous succession of events that made 1991 one of the fastest years of the century, so full of irreversible changes and historic fractures. It began with a war in the Persian Gulf that was impossible to associate with any previous military conflict, not only because of the technological disparity of the adversaries but also on account of the virtual and phantasmagoric nature of its media coverage, and closed with a good part of Europe signing the Maastricht Treaty for a Union that traced an unprecedented political geography for the continent. And between the ‘desert storm’ that put the post-Berlin world order to the test, and the shared dream of the United States of Europe, a convulsion in the East that shattered the Soviet Union to pieces and tore the Yugoslavian Federation altogether, giving rise to a handful of new countries that made it necessary to redraw all maps.

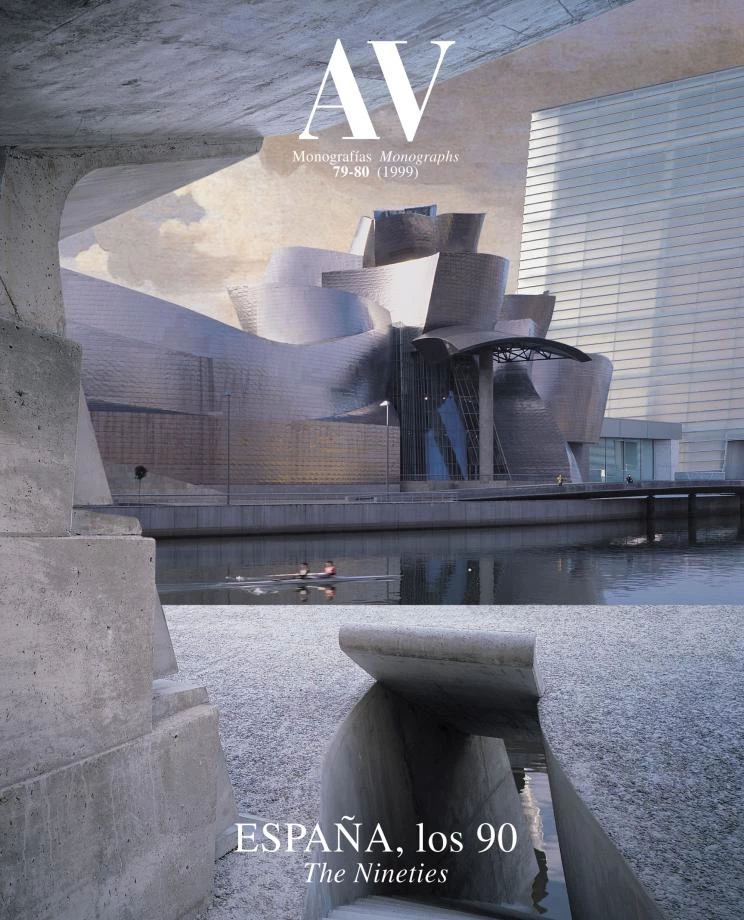

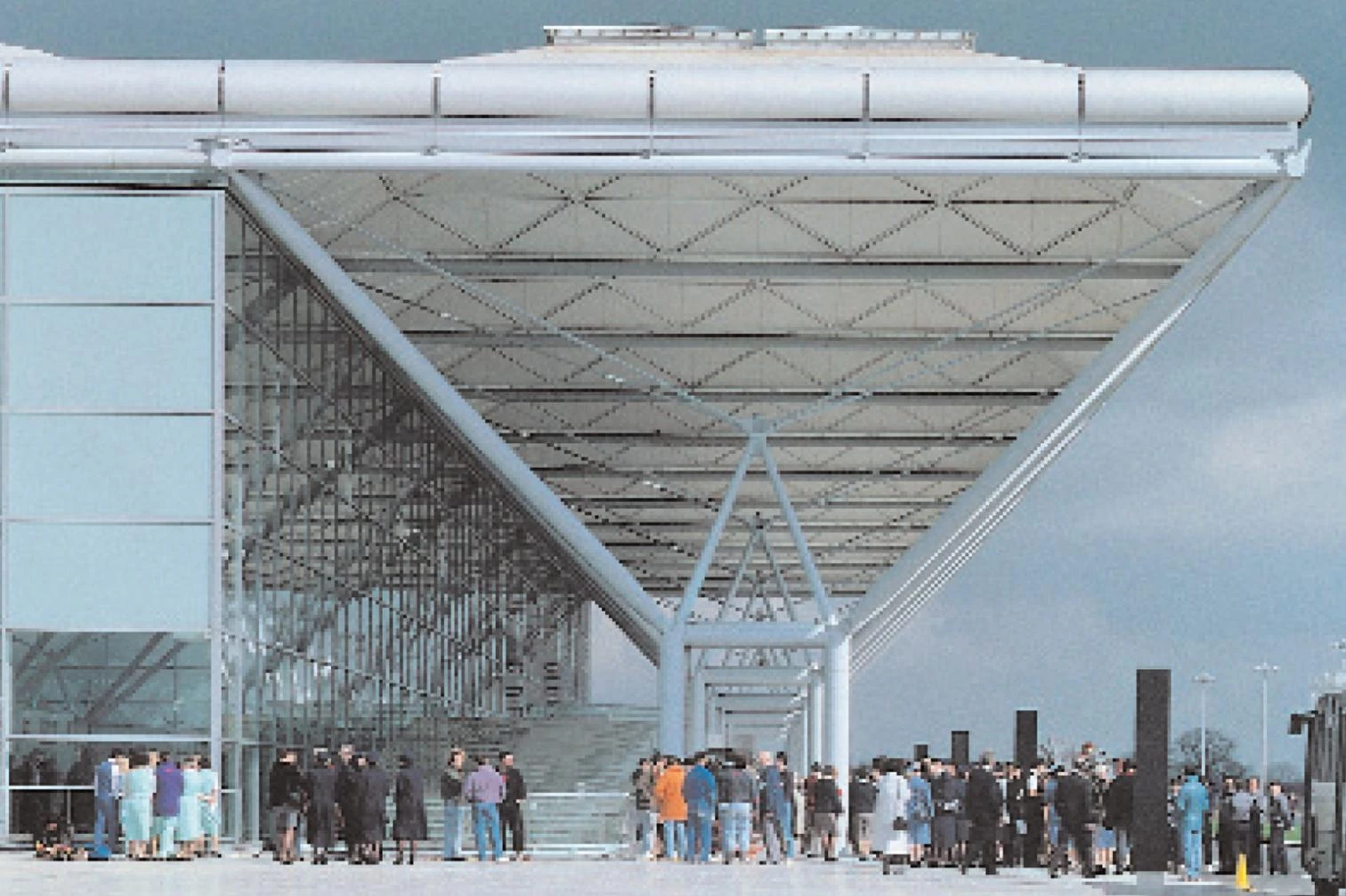

Norman Foster recovers the expectation of the first air travel with the terminal of the third London airport, Stansted, a diaphanous space covered by a modular juxtaposition of light, shallow vaults.

In architecture, this accelerated year was perfectly embodied by swift buildings at the service of the communication and transport networks that hold the globe together with their densely-woven skein. London’s third airport at Stansted is but a small node of that global web, but the terminal built by the British Norman Foster is so innovative in type and so elegant in its luminous and light geometries that shortly after being inaugurated by Queen Elizabeth II it won Europe’s Mies van der Rohe Award, a distinction granted by a jury that gathered in Barcelona, practically in the shade of the architect’s telecommunication tower, the slender silhouette of which already rises on Mount Collserola. Like its controversial counterpoint, the sculptural tower built by Santiago Calatrava within the Olympic ring of Montjuïc, this construction reflects the gusto of affluent societies for structures turned into spectacles, of the kind that has also reached Madrid in the form of the Reina Sofía Museum’s glass elevator shafts, a work of another Brit, Ian Ritchie.

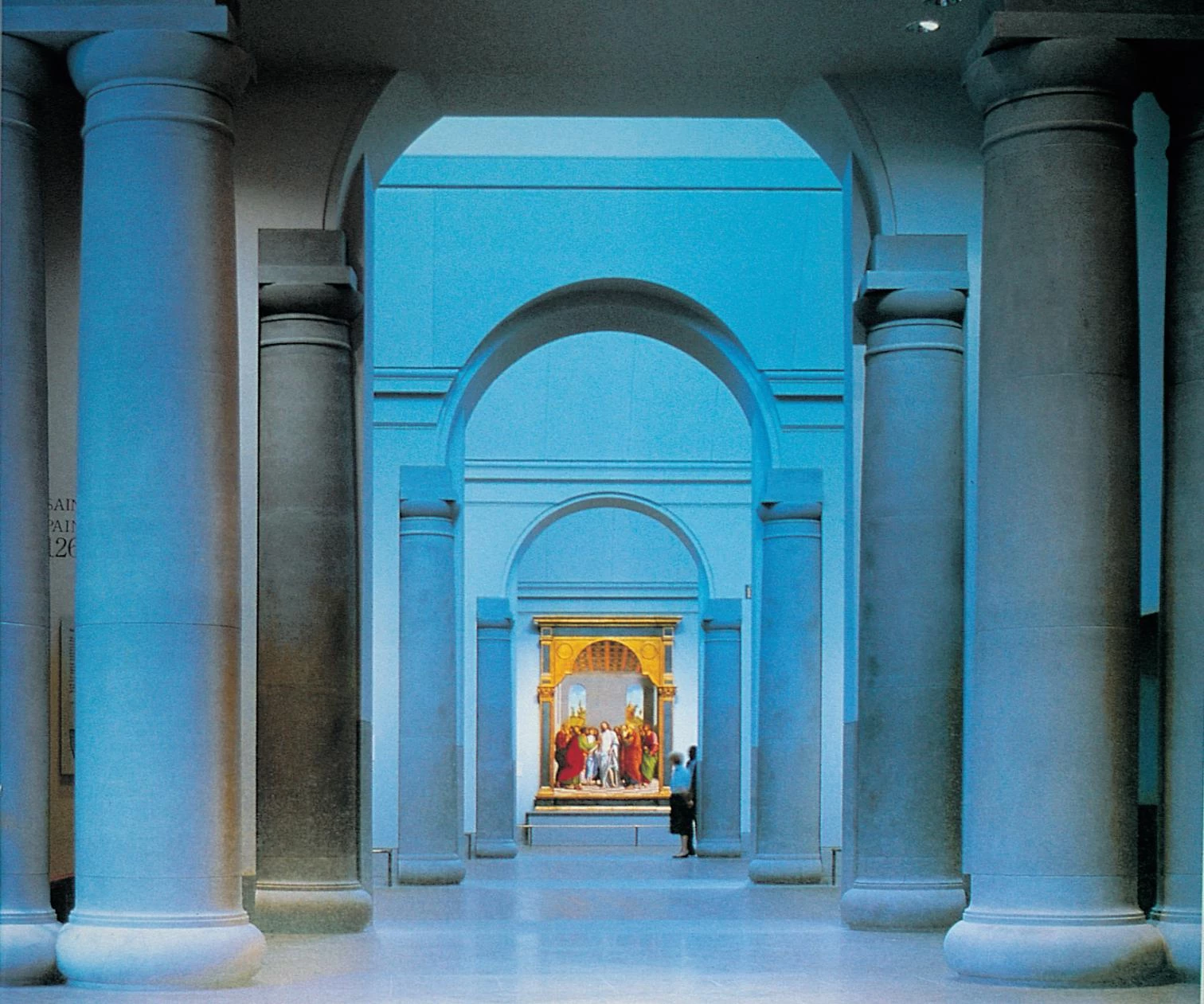

Twenty-five years after the publication of his book Complexity and Contradiction, Robert Venturi wins the Pritzker and expands the National Gallery in London with the approval of the most conservative sectors.

Paradoxically, glass-and-steel high-tech seems to be more welcome on the continent than in its home country, and though the teams building the English Channel railway tunnel between Dover and Calais finally met underwater in December 1990, connecting Great Britain to the rest of Europe both physically and symbolically, London remains under the conservative tutelage of the Prince of Wales, who opposed the National Gallery’s enlargement in the same language that the English freely export to France, Germany or Spain. The museum’s extension was finally carried out according to the project drawn up by the American Robert Venturi, and finished this year, in happy coincidence with the 25th anniversary of Complexity and Contradiction, the book published by the MoMA which sparked the ideological revolution spearheaded by the Philadelphia architect, and with a Pritzker that acknowledges Venturi’s intellectual influence on contemporary architecture. (To close the circle of coincidences, Venturi earned the prize a year after Aldo Rossi, the Milanese who crystallized a simultaneous theoretical revolution in Europe with The Architecture of the City, which also now celebrated its first quarter-century.)

The first Biennial of Architecture sums up a decade in which Spain has put forth works such as the center of Puerta de Toledo, by Navarro Baldeweg (above), or La Llauna School, by Miralles and Pinós (below).

Feverishly immersed in the preparations for the Columbian centenary festivities, the Seville Expo and the Barcelona Olympics, Spain celebrated its first Biennial of Architecture, which provided a pretext to look back on the ‘prodigious decade’ of the eighties with more narcissism than critical spirit. Unaccustomed to receiving the congratulations of the world, Spaniards relish their fifteen minutes of fame with naïve conceit and blissful amnesia, nostalgically ruminating a decade that was golden for buildings and bronze for cities. In placid coexistence, the generation of grandfathers fires its final shots, including some very loud ones by Sáenz de Oíza, who after the residential ‘bullring’ on Madrid’s M-30 highway now wrapped up a huge Convention Center in Santander; the generation of fathers savors professional maturity, led by Rafael Moneo, whose first post-Harvard year back in Madrid won him two major international competitions, for the Museum of Modern Art and Architecture in Stockholm and the Film Palace in Venice’s Lido; and the generation of sons and daughters presents its credentials for the changing of the guard, with a few brilliant cases like Enric Miralles, who in conjunction with wife and partner Carme Pinós is busy completing a handful of interventions of a fascinating lyrical intensity, from the school of La Llauna to the cemetery of Igualada.

But in the chapter of works completed in Spain, the most brilliant was Seville’s Santa Justa Station, terminal of the bullet train that links the Andalusian capital to Madrid, and a key part of the socialist government’s efforts to modernize the country while mitigating regional imbalances. Here Antonio Cruz and Antonio Ortiz, two disciples of Moneo, have surpassed their master, at least in the area of transport, for neither the other end of the high-speed railway line, Madrid’s Atocha Station, nor the simultaneously executed airport of Seville, both built by Moneo under the ambiguously historicist curse of Córdoba’s Mosque, can compare with the Sevillian project. Santa Justa is a contextual and innovative work of unusual clarity and elegance that will long outlive the ruckus of pavilions on the isle of La Cartuja, as the emblem of an at once traditional and contemporary south that quickens its pace without renouncing its identity.

On the eve of the Universal Exposition in Seville, Cruz and Ortiz finish Santa Justa Station, a large brick vestibule with corrugated metal roofing that speaks of both a traditional and contemporary south.

The Barcelona that gets ready to host the Olympic Games is no more inclined to spurn the signs that make it distinct, so while the city refurbishes several zones and builds new sport arenas, it rejuvenates the architectural landmarks around which its cultural life revolves. A case in point is the Palau de la Música Catalana, a building by Domènech i Montaner that Óscar Tusquets enlarged in an operation that seemed interminable. Its reopening in 1991 coincided with the finishing of another ‘palace’, a sport complex in this case: the Palau Sant Jordi, constructed by the Japanese Arata Isozaki on the hill of Montjuïc, will be the largest covered venue of the Olympic celebrations, second in importance only to the old stadium beside it which the Italian Gregotti has renovated for the purpose. Amid the masts of cranes and the roar of machines, time accelerates as well for Barcelona, Seville and Spain, on this Columbian eve that is witnessing the mutation of all of Europe.