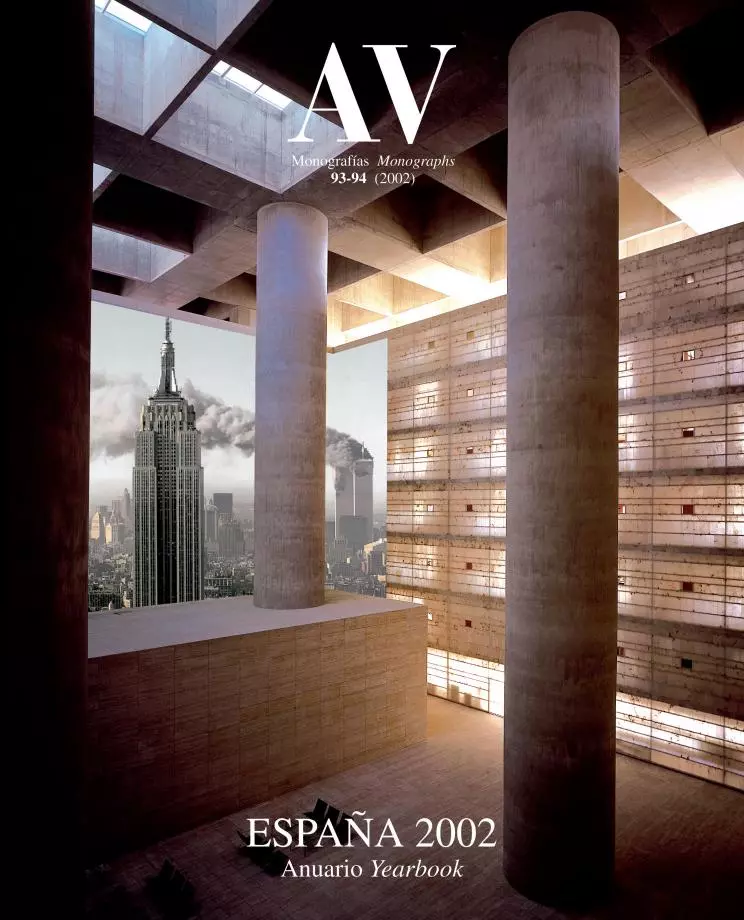

Towers of doom

The destruction of the Twin Towers in New York was of such historical relevance that it rendered anecdotal the remaining events of the year.

Any recapitulation of the year will inevitably hinge around the tragedy of 11 September. The number 2001 evoked the metaphysical futurism of Kubrick, but from now on it will be undivorceable from the image of two passenger planes crashing into Manhattan’s tallest skyscrapers. When they were finished in 1976, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were the planet’s tallest, and a true ‘space odyssey’ in the technical feat of their implausible slenderness and double height record. A quarter-century later, the sizzling rubble in Ground Zero buried the vertical odyssey in the horizontal and smoking space of a ruin. Alongside several thousands of victims, here lie the confidence in the safety of technical culture, the cosmopolitan aplomb of economic globalization and the political innocence of a young empire.

After a winter with Kahn’s muted centennial, spring started with the awarding of the Pritzker Prize to Herzog & de Meuron.

This could well have been the year of European masters in America. It was the centenary of Louis Kahn, the Estonia-born architect who called the modern dogmas into question from his base in Philadelphia, and that of José Luis Sert, the Catalan disciple of Le Corbusier who after the Spanish Civil War went into exile in the United States: two eminent anniversaries joined in the summer by two major New York exhibitions on Mies, the German master who carried out the second half of his career in Chicago. In the end, the protagonist of the period would be neither of the three Americans-by-adoption, but an architect of Japanese origins born in Seattle and trained in New York, who set up his practice in Detroit: Minoru Yamasaki, the destruction of whose Twin Towers marked the year indelibly.

Winter Geometries

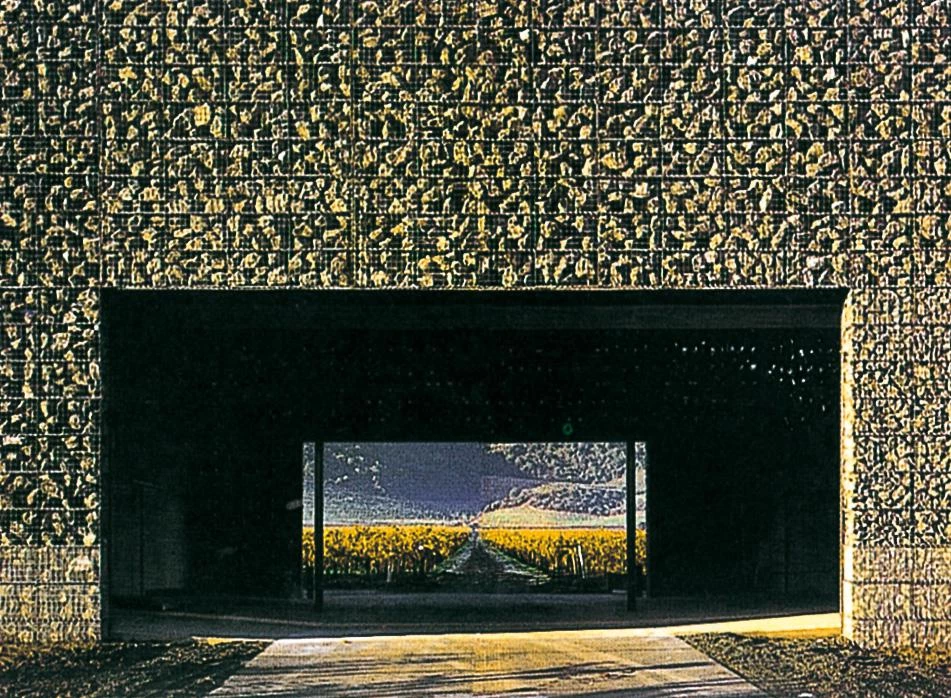

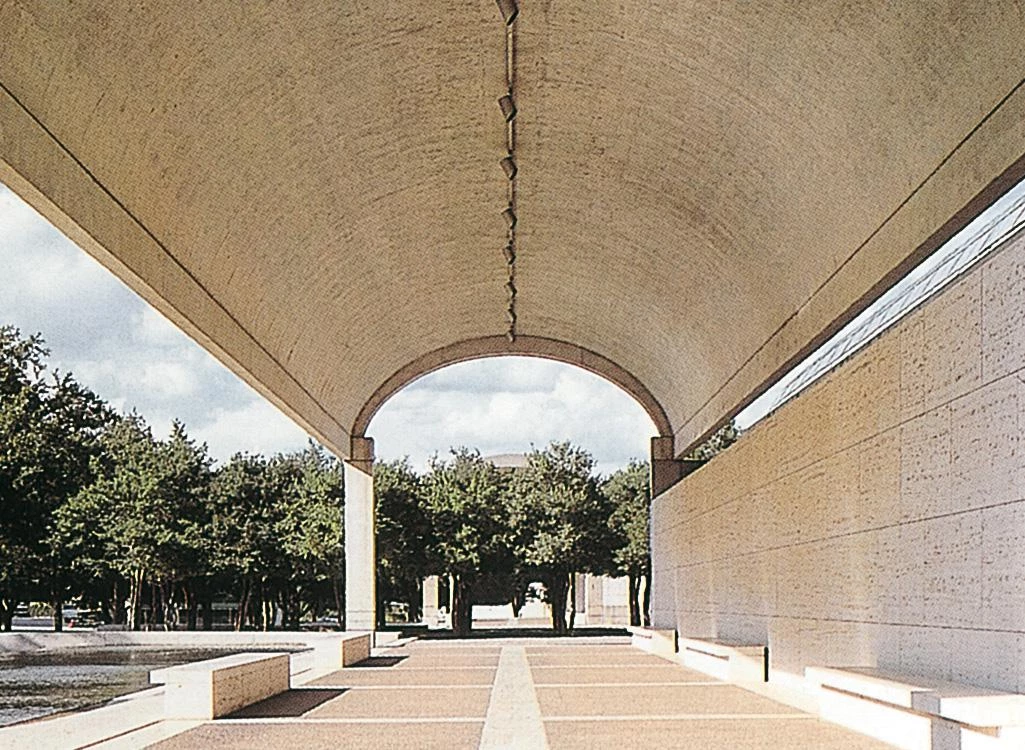

The winter season burned flameless. This slow combustion consumed a near unnoticed Kahn centennial, an architect of essential geometries that try to hold time in an eternal present, while the fallen leaves of laurels were bestowed, in the form of the FAD, on the Fine Arts Museum of Castellón, opened by Moreno Mansilla & Tuñón in January, and in that of the Biennial of Architecture prize on the Kursaal of Rafael Moneo, who simultaneously received the Mies van der Rohe award – in a sad edition marked by the death of its driving force, Ignasi de Solà-Morales, the Catalan critic and historian who rebuilt in Barcelona the master’s mythical 1929 pavilion. Two tributes to two works of reductive geometry that establish cubic genealogies between Moneo and his disciples, stressing the continued validity in Spain of a certain minimalism that aims to be abstract and material, echoes of which would also be heard in the hollow prism of Alberto Campo Baeza’s Caja de Ahorros in Granada, in the sculptural volume of Guillermo Vázquez Consuegra’s Museum of Enlightenment in Valencia, or in the efficient forms of Carlos Ferrater’s congress center in Barcelona, also winner of a National Prize.

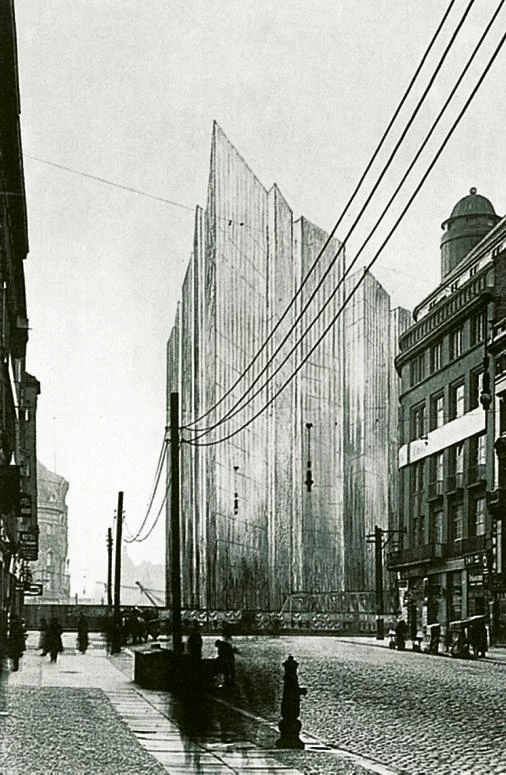

Two New York museums collaborated to set up a large exhibition on Mies, opened in summer. While the MoMA, custodian of the master’s archive, showed his Berlin period, the Whitney gathered his works in America.

Pyres of Spring

Spring announced itself with the ritual proclamation of the winner of the Pritzker Prize, which from its base in Chicago has become the world’s most prestigious architectural distinction, and for the tenth consecutive year now avoided landing on an American, manifesting the low moment that architecture is living in the new continent. The chosen ones, who received the trophy in Thomas Jefferson’s mythical Monticello, were the Swiss Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, partners based in Basel who combine construction and landscape, art and everyday life, to build a tactile and exact architecture that constitutes a pole of reference in the international debate, and which will soon be present in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Barcelona and Madrid; an oeuvre providing an archaic reflection on nature and the materiality of the living that encourages one to question our relationship with the environment and all those beings inhabiting the planet, a currently ailing relationship which the veterinary and health crises that have sprinkled European territory with pyres of sacrificed animals suddenly revealed under a violent light.

Two New York museums collaborated to set up a large exhibition on Mies, opened in summer. While the MoMA, custodian of the master’s archive, showed his Berlin period, the Whitney gathered his works in America.

A Summer of Museums

Summer began with the Mies van der Rohe exhibitions, and the image of the great modern master that these New York shows presented could not have been more disparate. In the pedagogical and critical narrative of the MoMA, the Berlin Mies came across as contextual, landscapist, expressionist, and subjective; in the exquisite and exhaustive homage of the Whitney, the American Mies was reductive and self-referring in his pursuit of universality. Meanwhile, the master architect’s native Mitteleuropa witnessed the completion of a whole new generation of museums, many containing echoes of the convulsion that sent him to exile: the Schieles and Kokoschkas in Vienna’s new museum quarter, built by Ortner & Ortner in the old imperial stables; the objects and documents in Berlin’s Jewish Museum, which finally opened, twelve years after Daniel Libeskind’s first drawings of a zigzagging, fractured ray of lightning; or the Nazi scenarios of the Nuremberg memorial, designed by Günther Domenig in the congress palace that Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect, never got to finish. But the summer that began in New York was to end there, on an 11 September that slit open the latent violence of our world, and chose the city of skyscrapers as a theater of terror projecting its threat over our future.

Autumn on Fire

Ground Zero in Manhattan and the rough landscapes of Afghanistan were the two desolate scenes of an autumn on fire which in a war against terrorism resuscitated the phantom of conflict between civilizations, and put the Islamic world on the bench of the accused. In the dust storm of mullahs and muyaidins, the architectural signs that marked a different Islam disappeared, and Muslim culture narrowed down to terms like taliban, jihad or burkha, converted into fetishes of a hostile universe. Neither the ceremony held in Syria for the model Aga Khan Award, with the plural and luminous portrayal of an Islam that does not renounce modernity, nor the completion in Egypt of the library of Alexandria, a colossal secular monument designed by the Norwegians of Snøhetta, could help neutralize a climate of suspicion and fear.

To the same New York that had inaugurated the summer season arrived the most cruel of autumns, with the attack which destroyed an architectural symbol of the power of the United States: the Twin Towers of Manhattan.

Meanwhile on the Iberian Peninsula (for centuries witness to the difficult coexistence of the Christian West and Islam) emblematic works of two cities with a strong Muslim heritage were commissioned to Northern Europeans, the Dutch Rem Koolhaas in the Córdoba of the Caliphate and the Brit David Chipperfield in Mudejar Teruel, testing new mixtures and new dialogues in a continent where a single currency will start in 2002, a year which despite everything must begin with hope. The closing one celebrated the anniversary of Walt Disney, a 20th-century genius who struck fame during the Depression with the optimistic parable of The Three Little Pigs, who were not afraid of the big bad wolf of economic crisis – in the same way that we should try not to be afraid of the fictitious big bad wolf of Islam or the very real big bad wolf of terror.