The architecture of the fold has one of its insignia buildings in MVRDV’s Villa VPRO, whose warped forms do not wish to express the world’s fractures, but attempt to adapt to its variable condition.

The new architecture bends to circumstances. Abandoning the challenging catastrophic images of deconstructivism, the latest avant-garde movements adapt to the universe through folds and bends. If the architects who fed on Derrida built broken buildings, those who now cite Deleuze design friendly warped forms: the trend is no longer to express the world’s fractures, but to adapt to its variable condition. This architecture recognizes the social and economic forces that shape it, and makes itself flexible in order to accommodate them: it bends so as not to break apart, and the folds symbolically express such flexible outlook. Reality is not represented, but negotiated with a pragmatism that prefers compromise to conflict, that incorporates contingency with tactical ductility, and that confronts complexity through geometric distortion. Deconstruction tore up the regular meshes of reason; the folds inspired by Deleuze merely deform them.

Paradoxically, this obliging architecture turns out to be the more subversive. The floor slab that curves up into a wall confuses the horizontal and the vertical; the warped flooring that brings the topography of the land into the building blurs the limits between interior and exterior; and the plane that folds and twists disrupts our perceptive hypotheses with the dizzying efficiency of a Moebius band. The most frequent reaction to these perverse typologies is perplexity. According to its designers, these strange forms are the result of external circumstances, forces which mold the spaces the way the weight of trapeze artists deforms the net they perform on. Nevertheless these unexpected geometries refer more to the computer programs used by film animation or the aeronautical industry to represent dream landscapes or streamlined fuselages. What is drawable is imaginable, and begins to be buildable; external circumstrances do not affect the result, but are used as alibis and stimuli for processes of extraordinary formal invention.

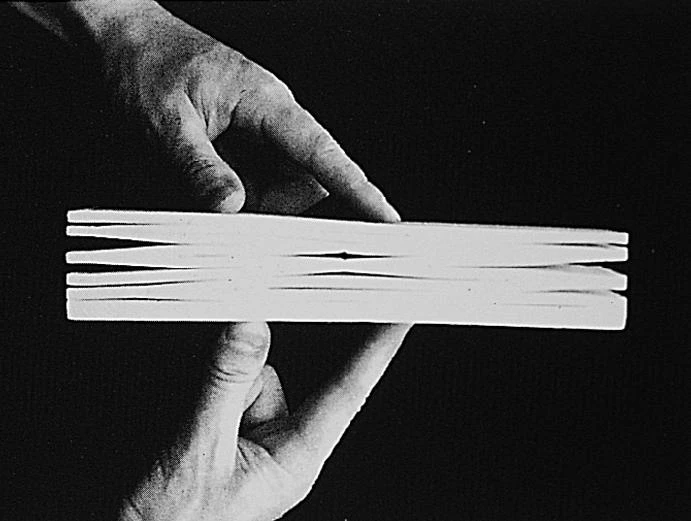

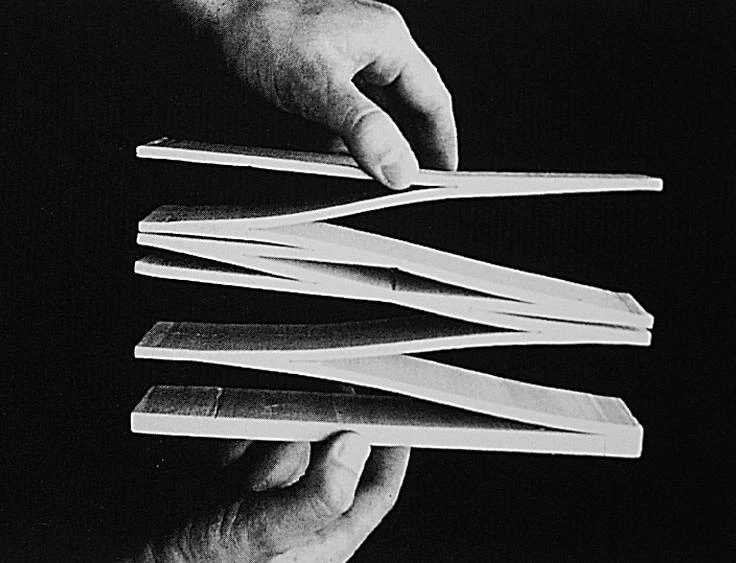

Dizzying spaces connect the different levels of the Villa VPRO. In the urban project for Leidschenveen, MVRDV multiply the available land pleating it like the bellows of an accordion.

Villa VPRO is one admirable example of fold architecture. Built in the Dutch city of Hilversum by the young Rotterdam team MVRDV (Winy Maas, Jacob van Rijs, Nathalie de Vries), it houses the headquarters of a public radio and television station, known for its unconventional character. The building has endeavored to conserve the informal spirit of the organization, through what at first looks like an enormous parking lot with slanted floors, random voids and irregular furniture: some slabs warp to merge with those of the higher story, and others fold upon themselves like blankets in a closet; perforations and dizzying courtyards appear everywhere, visually connecting the different levels while letting light shine into the areas removed from the perimeter; and fleeing from the wall-to-wall carpeting and traditional furnishing of offices, the interior space is decorated with numerous rugs spread out over the cement, near-surreal chandeliers and furniture pieces of all types.

To emphasize its character as an interior landscape, the building has no facades. Its facade is the section: the folded floors prolong to the outer edge, where large sheets of glass take the place of the initially intended but eventually impractical to install hot-air curtains. Neither is there a roof in the true sense of the word: in its stead is a large stretch of grass dotted with sockets and computer outlets, in the middle of which rises a glazed meeting room that can only be accessed by crossing this work-recreation lawn. And inside this huge box unfolds the stimulating and chaotic panorama of what its authors call an ‘artificial ecology’ generated by a ‘data landscape’: a motley environment, halfway between industrial and domestic, that becomes decidedly theatrical in the cafeteria with its tables arranged in tiers or in the enormous chimney where colossal logs burn permanently.

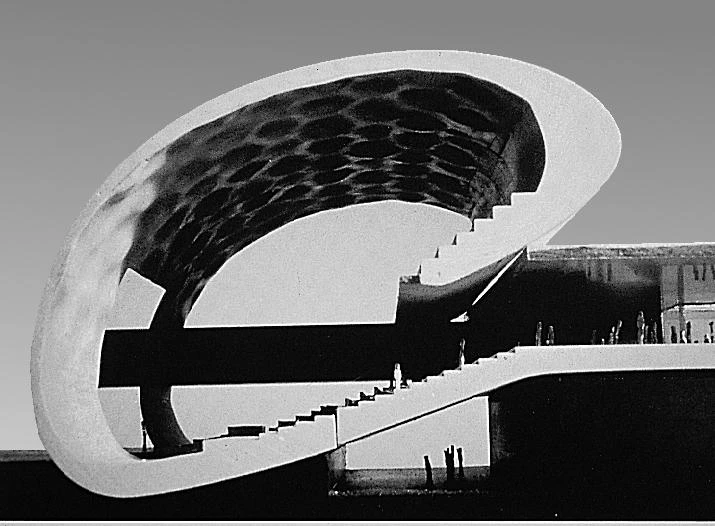

Folds and loops are employed profusely in the work of Rem Koolhaas, the indisputable master of the latest generation of Dutch architects; the Luxor Theatre in Rotterdam and the Educatorium in Utrecht.

Many influences converge in the VPRO headquarters: the humanistic structuralism of the Dutch Aldo van Eyck and Herman Hertzberger, the latter of whom left his finest administrative realization in the labyrinthian order of Centraal Beheer; the rather surreal pragmatism and passion for congestion of the Rotterdam architect Rem Koolhaas, whom one of MVRDV’s members has in the past collaborated with; the growing popularity of landscaping in a country whose population density is becoming comparable to Japan’s; and the episodic effect of AngloSaxon theory, which in its fervor of everything French currently serves a menu mixing Debord’s situationism with Thom’s theory of catastrophes and Deleuze’s pli, all conventiently spiced with biological morphogenesis, mathematical topology and the capricious geometries of the computer. In a recent book, Óscar Tusquets describes his astonishment as a university student on discovering the artificiality of the horizontal floor, a truly human creation of something that does not exist in nature.And perhaps the term ‘artificial ecology’ applies more accurately to this magical and exact discovery than to the concrete dunes of the imaginative young Dutch architects.

The Open Section

If modern architects invented the open plan in the twenties, in the nineties, the Dutch Rem Koolhaas and his disciples have elaborated the open section: space no longer flows in a horizontal direction, but stretches vertically through floors that slant and curve, folding like accordions or curling like frozen concrete waves. In MVRDV’s urban plan for Leidschenveen, the available land multiplies like bellows, using a method of connecting levels through ramps and warps that Koolhaas had previously employed in the contemporary art center of Karlsruhe and in the libraries of Jussieu. And the loops, which were already present in the same architect’s project for the Grande Bibliothèque of Paris, now also characterize the floor slabs of the recently completed Educatorium in Utrecht University or the spectacular design for the Luxor Theater in Rotterdam. In the tradition of formal exploration that comes from Le Corbusier, Terragni and cubism, it is nowadays hard to find a more gifted and perverse architect than the master of the young MVRDV team, the brilliant and restless Dutchman who answers to the name of Rem Koolhaas.