Private Houses can be very public. The Un-Private House, a summer exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, uses domestic projects as a seismograph that records the quakes of the future. By putting an ear to the womb that gestates the forms of the century to come, and through the example of 26 houses, Terence Riley – curator of the show and director of the MoMA’s architecture department –traces the changes that the family and the notions of privacy and leisure have undergone in recent years. In this new domestic landscape, private hous-es are presented as public manifestos of time in motion. Exhibitionist and loquacious, they are houses we talk about, and houses that speak with the eloquence of their spaces... and, we must add, of their authors, who often present their projects with a formidable deployment of rhetoric artillery.

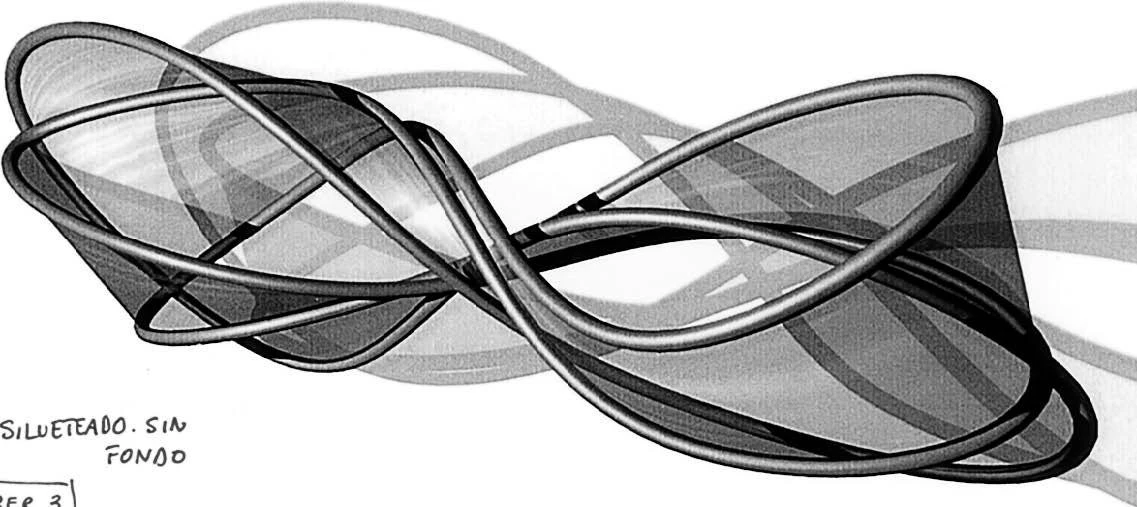

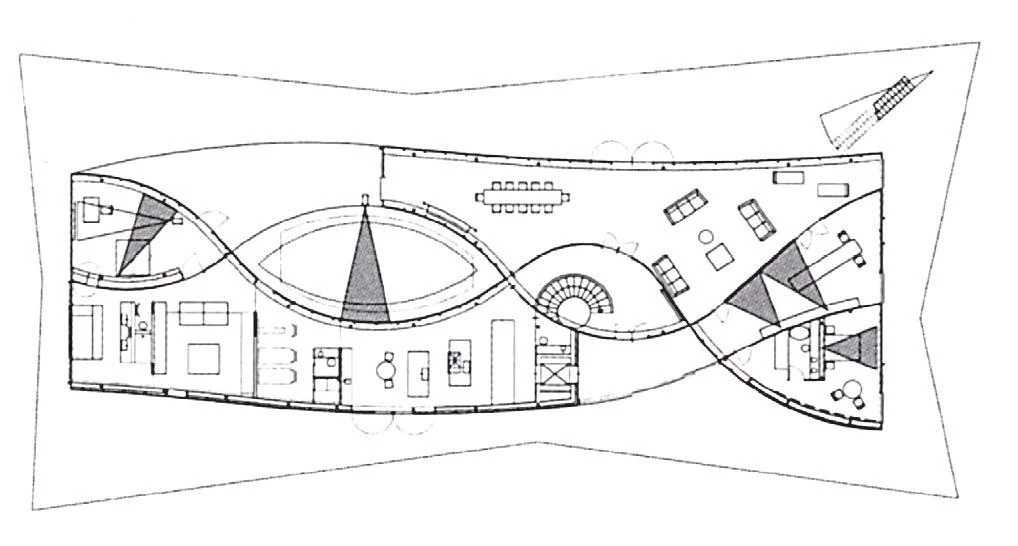

The built result of reflections compiled by the author of MOVE, the Möbius house designed by Ben van Berkel combines domestic activities in a skein of cyclical and continuous circulation pathways.

Nothing can exemplify this discursive armor plating better than the Möbius House, built outside Amsterdam by the young Ben van Berkel, which has arrived at its world première in New York City in the wake of an exceptional media bombing. The house lends itself to publications accompanied by a wide range of schemes and diagrams illustrating its inspiration on the Möbius strip, a wealth of esthetic and philosophical references, from Max Bense to Deleuze, and extensive credit descriptions acknowledging, for instance, the Amsterdam agency that complemented the usual photographic shoot with a collection of images showing the house inhabited by sexy male and female models.

Such a publicity strategy has put the house in the spring issues of very influential architecture magazines, from the German Bauwelt to the Italian Domus and from the French L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui to the Japanese a+u, whose March edition is provocatively entitled ‘Rem & Ben,’ establishing a parallel between Koolhaas and his compatriot. Van Berkel, born in 1957, has gotten a new name – UN Studio, for United Net – for the office he shares with his wife, art historian Caroline Bos, and has recently designed his own book-manifesto. Following the example of Koolhaas, whose OMA firm and 1,344-page S,M,L,XL set a pattern of self-presentation faithfully followed by other Dutch architects (such as Winy Maas’s MVRDV and its 736-page FARMAX), UN Studio has come up with 816 pages in three volumes under the title MOVE, which records the shifting movements of architecture and advertising, describing architects as ‘superstars’ and ‘fashion designers of the future.’

Represented in the MoMA exhibition by the unusual project of the Kramlich house in California, Herzog & de Meuron employ in Rudin’s house at Leymen the archetypal forms of domestic architecture.

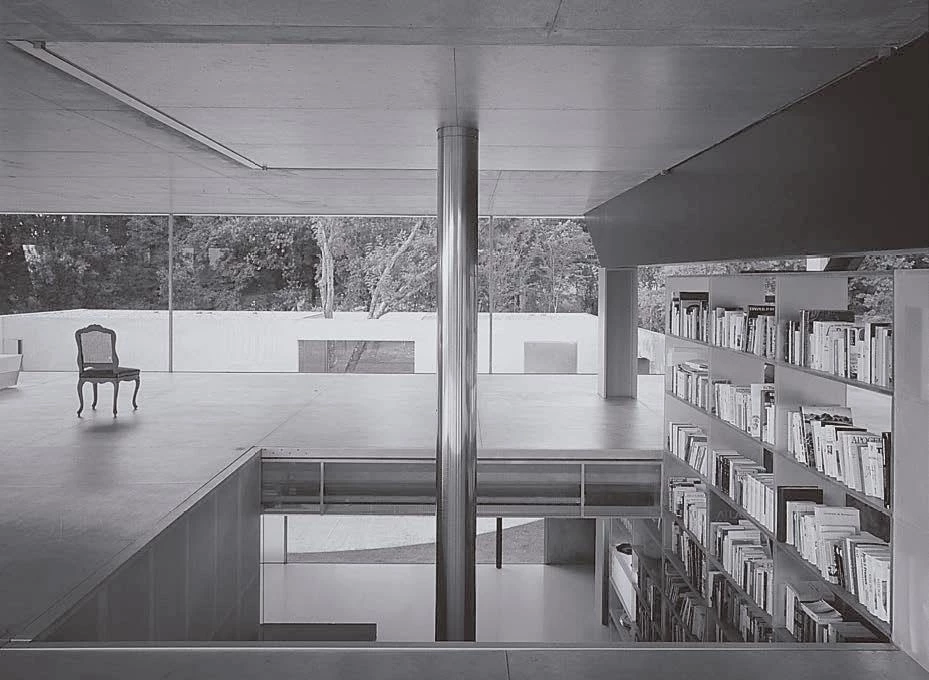

The real-life result of this literary outburst is a concrete and glass house in the shape of the number 8, where the residents’ routines cross and diverge in the course of tangled routes that connect the spaces with exhausting transits and chinks of light. Built over six years by a married couple of professionals who collect paintings by the CoBrA group and wanted to own a masterwork of architecture, the Möbius House inevitably recalls the swift, sharp-edged suspended forms of Zaha Hadid, in whose London office the Dutch architect worked for a time: a circumstance that is not too surprising if we remember that his most important work prior to this, the Erasmus Bridge in Rotterdam, referred to the sculptural expressionism of Santiago Calatrava, who had also once taken in Van Berkel at the start of his professional life.

In contrast to this formal exuberance, the latest house of the Swiss partners Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron (who are represented at the MoMA by a still unexecuted project, the Kramlich House) addresses the domestic realm with exemplary laconism. Set amongst the placid undulating meadows of the French region close to the meeting of the Swiss and German borders, the house they have built for Hanspeter Rudin at Leymen is a prism with a pitched roof that evokes the pure simplicity of a child’s drawing, while floating above ground, weightless and surreal, held up by piles in metaphysical solemnity.

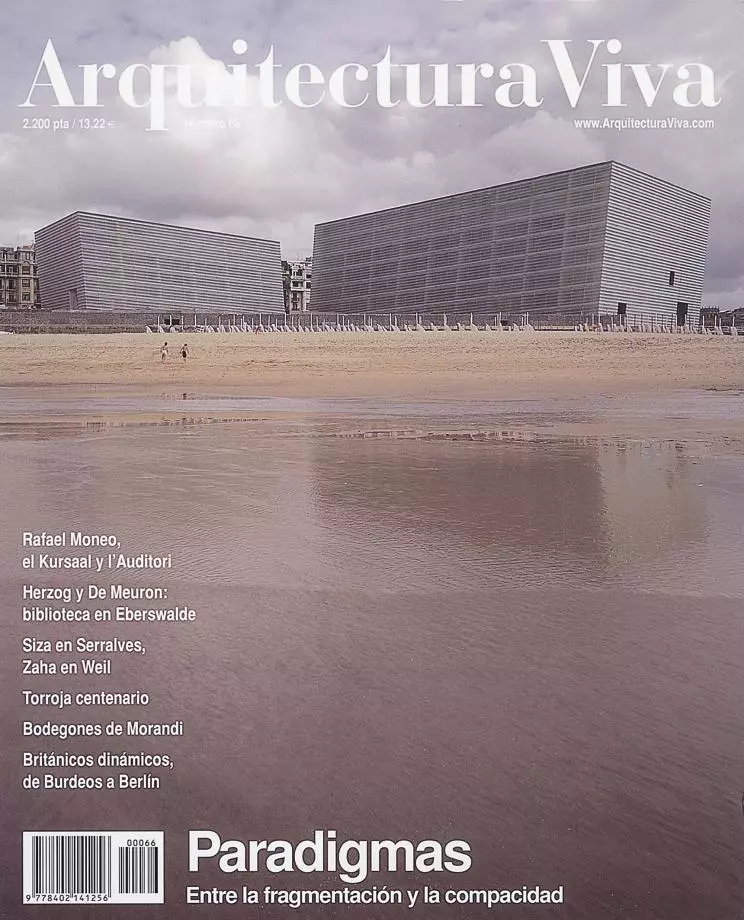

The conflict between public and private is addressed with introspection in Sejima’s House M, with exhibitionism in Koolhaas’ Bordeaux villa and with loquacity in Ban’s Curtain Wall House.

At once archetypical and unusual, this house al-ludes to the maxims the architects received from Aldo Rossi, who instilled in them the intellectual importance of basic shapes, as well as to their early association with Joseph Beuys, from whom they learned the emotional impact of materials. But here visual clarity and tactile wisdom are surpassed by a strange and clear-cut object: a compact concrete block, set on a tray that renders it light and portable, its precision eroded by rain and lichen, and placed on a floor of loam that continues in the mud walls flanking the dwelling’s vertebral staircase, whose steps, perforating the platform, rise from the ground below all the way to the topmost skylight.

Posed on this magic carpet like a Magritte in ironic levitation, and perforated with anthropomorphic orifices like a pumpkin drawn by Steinberg, the house seems at once familiar and mysterious, and such friendly hermetism hits us with an archaic emotion absent in most of the domestic choreographies at the MoMA. Almost all those public and publicized houses pale against the intimate intensity of this private house hardly anyone talks about.

Public Intimacies

Some of the houses on display at the MoMA address the contradiction between the intimacy of the domestic sphere and the public condition of urban housing, a conflict that comes to an extreme in Tokyo, where the residential refinement of Japanese tradition confronts the energetic chaos of the metropolis. Here Shigeru Ban built his literal ‘Curtain Wall House’ by making the facade of the two upper floors a large canvas that, when drawn back, exposes the rooms to the onlooker on the street, who might as well be peering into a dollhouse: domestic life laid bare on a showcase. In the same city but with an antithetical sensibility, Kazuyo Sejima chose to bury her ‘House M’ and illuminate this intimate refuge through self-withdrawn courtyards that offer the street nothing more than the striped hermetism of their metal latticeworks. The conflict between private and public acquires a different dimension in suburban dwellings, where intimacy is violated not by neighbors, but by the voyeurism generated by hard publicity. A case in point is the residence that Rem Koolhaas built in the outskirts of Bordeaux for a paraplegic client, who transports himself on a large elevator platform, dealing with his disability with the help of a machine building that seems to demand the respectful distance his painful condition merits, yet has become one of the decade’s most exhibited houses, with a shameless-ness not too alien to the rough spirit of our times.