The surreal dwells among us. Far from just being an artistic and literary movement of the past century, surrealism is a dark pulse that shakes the present. The extraordinary popular success of the Dalí exhibition at Paris’s Pompidou and Madrid’s Reina Sofía proves – aside from the stubborn resilience of the artist as a media celebrity – how interests that we thought restricted to the historical avant-gardes are still current. Surreal architecture – soft and hairy, as the Figueres genius imagined it, or else based on the random assemblies of the cadavre exquis and the equivocal trompe l’oeil of metaphysical illusionism – has always had bad press, as befits its subversive character, which decomposes with an organic beat the frozen geometries of rationalism and corrupts with oneiric deliria the solar clarity of reason. This Dionysian inebriation has been however permanently present in our culture, barely veiled by the stern Apollonian conventions that protect the forms of social life.

Le Corbusier himself, who disdained surrealists, ended up interiorizing their lyrical irrationalism, and from the objets à reaction poétique to the symbolic volumes of the late work, the eye and hand of the architect shifted effortlessly from the machine à habiter to the machine à émouvoir. Beyond the fireplace with a lawn and the surreal still life of Parisian icons on Beistegui’s roof, the calfksin of the steel tube chairs or the artificial rocks of the Unité or La Tourette, the 20th century master explored the poetry of the unexpected and the attraction of the organic in the secret laboratory of his painting atelier, where the purism of the objets type was superseded by the sinuous forms of the female body and by the invocation of archaic symbols, placing the urge of carnal desire and the yearn for spiritual meaning within the technical landscape of functional architecture, whose rational mechanisms were thus sabotaged by the insolent intrusion of the primitive in its modern anatomy.

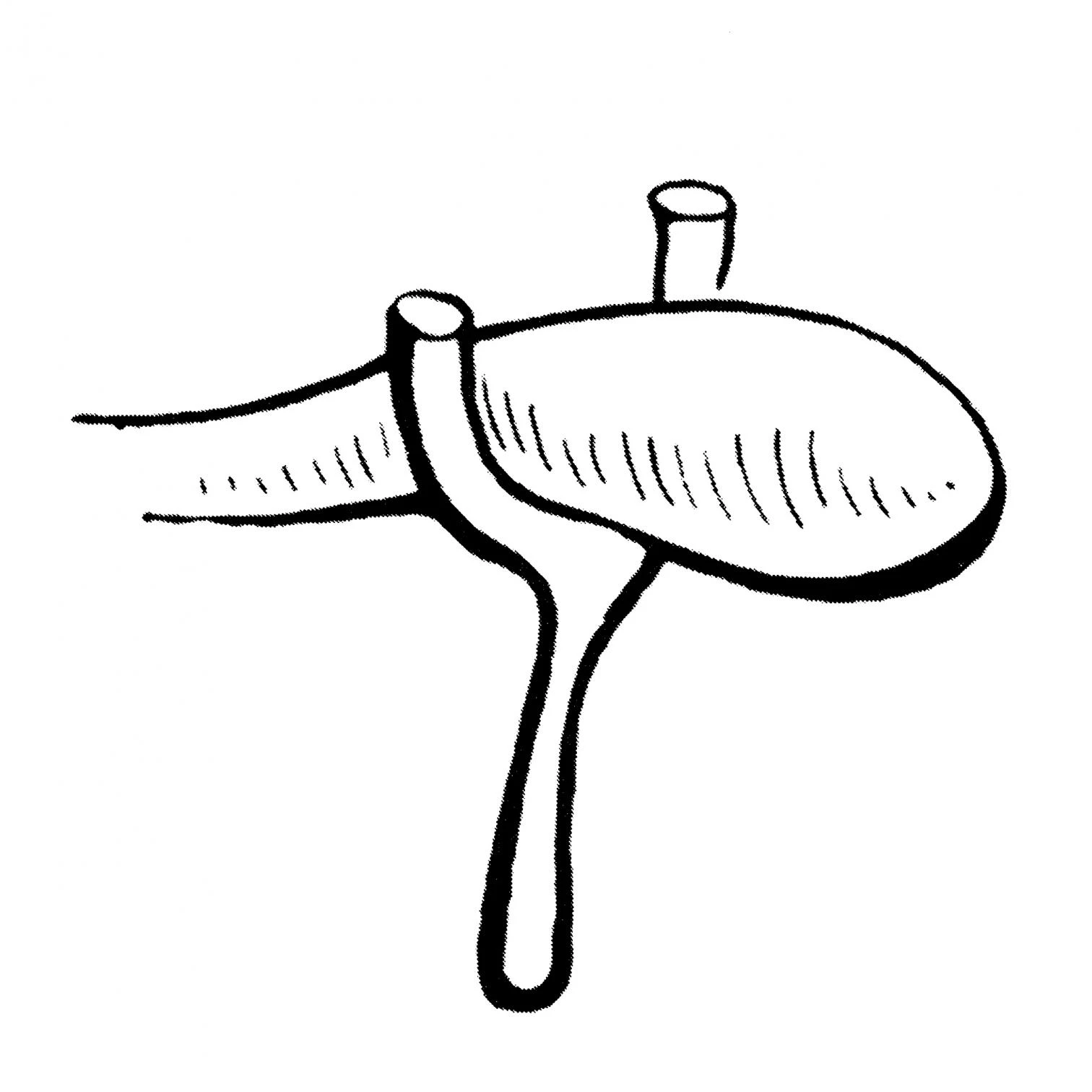

And something similar can be said about Rem Koolhaas, the architect who in our days has best fulfilled the role of public intellectual once played by Le Corbusier. In his case, the adoption of surrealism has been well documented, from the use in his projects of the cadavre exquis method to add without articulation dissimilar forms or functions – be it through the clashing of heteroclite volumes or the juxtaposition of functional bands –, to the advocacy of Dalí’s paranoid-critical method in Delirious New York, where the only repeated image is a drawing by the Catalan painter, a soft and viscous mass held by a branching support. This abridged representation of the link between the amorphous unconscious and the often insufficient crutches of reason is present in the articles and projects of this issue, which hopes to take stock of the present popularity of the formless without succumbing to its easy fascination or else giving up the severe rigor of rational thought.