The Aura of Art

Objects move through spaces of art, metamorphosed and mutated into a succession of identities which alter their meanings.

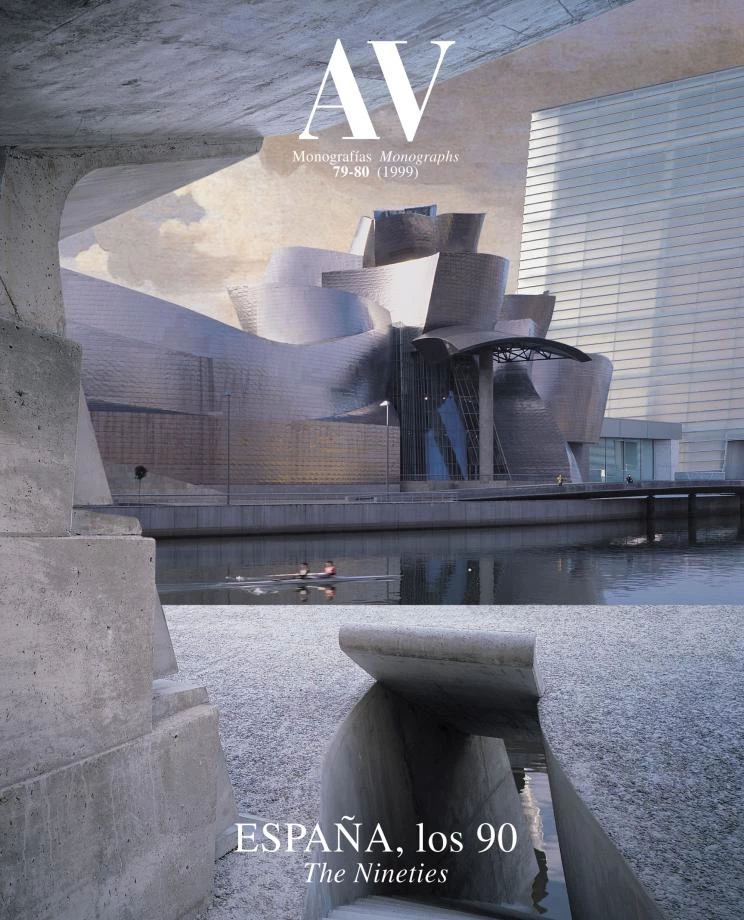

Gravitating toward the Prado Museum, the Reina Sofía Art Center (above) and Thyssen Foundation (below) each exhibit different interpretations of their contents through the architecture of their building headquarters.

Art is art and its spaces. Objects traverse time and come to us in various contexts that color our gaze and frame our attention in different ways. A canvas is not the same in the penumbra of the home and the even gleam of the museum, in the clutter of the studio and the motley confusion of a fair. The spaces often swallow up the objects, saving for us only its architectural marrow. The endless vaults of the Reina Sofía, the peach walls of the Thyssen and the gray enameled light of the Prado suck images off the walls in the same manner that the labyrinth of art fair stands grinds them to form an indifferent and blinding magma.

Viewed from the mezzanine level of the Crystal Pavilion in the Casa de Campo, Arco’s ephemeral architecture fully reveals its precarious condition as a traveling market, geometrical and feeble on the halogen-lit carpet, like a chaotic and fleeting camp. The drop curtain of the event both displays and devours art objects, regurgitating them like nomadic merchandise in an at once multiple and thematic bazaar, all luminiscent in the uncertain glare of commerce. The plural drone of trade drowns out any prophetic voices, and even the most inspired preachers, when removed from their pulpits and temples, blend in with hawkers holding forth from boxes in park corners.

The posh hustle and bustle of anonymous commercial centers and hotel lobbies turns paintings into glossy catalog illustrations. Inserted amongst the boutiques of an Azca subway, overlit by shop window bulbs and diagonal gazes, the symbolistic, castiza, guilty sexuality of Romero de Torres takes on the provocative, brash triviality that the shutters and filtered light of Córdoba always protected it from. And in the opposite direction, when exhibited on the desolate, inhospitable walls of a Sevillian barracks, the insufferable vacuity of Julian Schnabel acquires an ancient, solemn, somber graveness. Places make and unmake artists.

A Turrell construction in the garden of a Californian millionaire is a social event, one generating a chain of tepid twilight parties; the same perceptive explorations, transferred to the premises of a foundation on Madrid’s Calle Serrano, become amiable exercises on recreational physics. The Adoration of the Magi, the work of Mantegna that broke records in auction halls, was a magical, opaque everyday object on an easel in the restoration workshops of the Getty Museum in Malibu; our own Death of the Virgin, in turn, cannot help being captured by the echoes in the Prado of the writings of Eugenio d’Ors on the painting. Spaces sequester, contaminate and direct gazes.

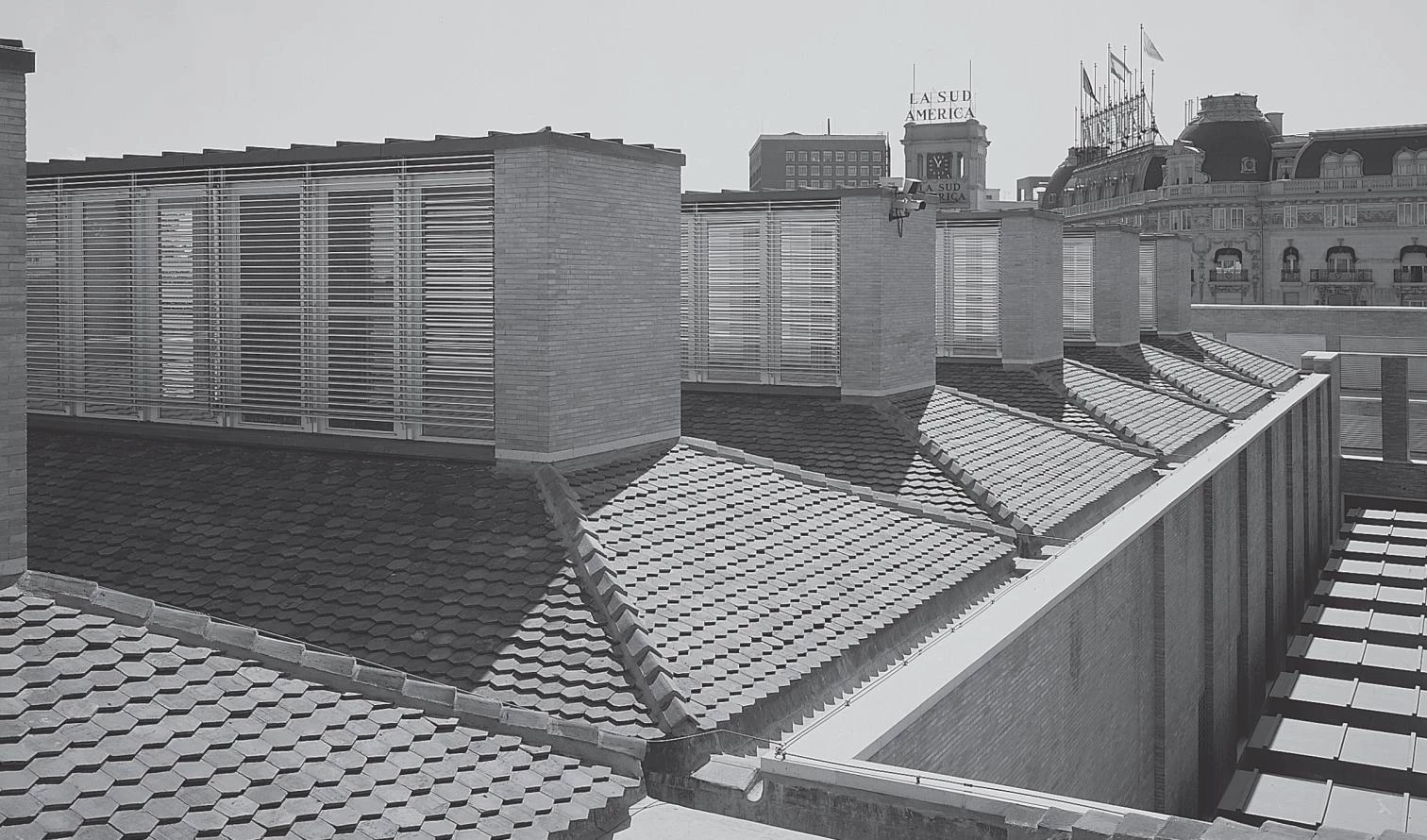

Spain’s best painting collections are exhibited in architectures of distinct character; the Villahermosa Palace (above) displays the contents of the Thyssen Foundation in the enfilade designed by Rafael Moneo; the Reina Sofía Center (below) houses contemporary art in the sober spaces of a former hospital; and the Prado Museum presents its canvases within the neoclassical setting of Juan de Villanueva.

The architectures of art accommodate narrations, but what better story than the stage itself. In ‘The Ages of Man’, that long-running series of at once secular and divine super productions, the monumental format of the premises gave epic eloquence to otherwise rather confusing scripts. The high Gothic vaults claimed for the firmament of the spirit many mediocre pieces salvaged from parishes, sacristies and all too human diocesan collections. The cathedral itself, which shares neither age nor distance with man, proved the best narration, and the civil populism of the idea behind the exhibition was translated to sacred ecstasy. What better propaganda than ashlar stones.

The Prado’s docile visitors go through the temporary exhibits in the orderly sequence indicated by arrows, filing before Caspar David Friedrichs or Goyas in a disciplined succession that gives the visit the imposed rhythm of a film session rather than the free, syncopated pace of a read: the Caprichos of the Marques de la Romana gets consumed with the same narrative tempo as the Chicago vignettes of Fray Pedro and the Maragato. This ductile disposition of audiences should serve the purposes of the new director, who proposes to change the order of the art works without altering the arrangement of the building’s interior layout: a commendable approach, not only because it would produce more intellectual than economic fatigue, but also because Villanueva’s vigorous architecture will stubbornly guide his steps.

The new period of austerity in public spending can prove beneficial here. It has checked the expansionist fever that, in hopes of centrifuging the Prado’s collections, had gone about colonizing the surroundings, with a proliferation of annexes that not even the eventual emptying of the Army Museum’s admirable and excessive galleries could restrain. Such fervent cultural metastasis would have stripped the Prado of its essence - the compact intensity that distinguishes it from all other museums, and which is inseparable from its accumulation of masterpieces. Meanwhile, the senseless enlargement project for the accommodation of ancillary facilities was curbed by the redhead ministress of Culture in what was her first decision on the job, a move she justified with the happy juridical expression of the extension not being ‘pacific’.

Across the street, the Villahermosa Palace - another building once eyed as an extension for the Prado - has swallowed its pictorial content in such a way that it is hard to abstract the skin of the canvases from the muscle of the masonry; the Thyssen collection is diluted in Rafael Moneo’s pink cup. The palatial enfilade organizes the paintings in quiet niches, the leafy brightness of Paseo del Prado can be discerned behind the white lattices, and one’s gaze slides over the polished marbles and the surfaces, tense like oilcloths, of hackneyed old masters. Among the works on display are about a hundred too many; when these are put away, along with the megalomaniac portraits gracing the foyer (there is still time for the baroness to pose for Lucien Freud in small format), then the architecture of Villahermosa shall have completed its artistic digestion and the museum will have met with its placid destiny.

Meanwhile, the clumsy packet that is the Reina Sofía continues its wandering trajectory, disconcerting and uncertain like its hermetic and painful architecture, which is full of prostheses that have hardly even served as crutches to a set of crippled constructions. The interminable vaults that shut out the light entomb everything contained within, enshrouding art. The luminous and frugal Antonio López of Albacete or Brussels have lain dead in those hospital corridors; only the ominous taxidermic carrousels of Bruce Nauman seem at home in that cold, hostile environment. Christo ought to propose a permanent wrapping for the luckless building, which preserves a tremor of emotion only in its granite Piranesian stairs.

Art objects make the round of the world’s art spaces and undergo metamorphoses and mutations, in a roguish succession of identities that alters both their position and their meaning. On rare occasions, the architecture of the container harmonizes with the gem, and the inert stone shines with an inner light. The aura of art, paled by habit and the opaque gaze, reappears under the roof of the place: architecture is the aura of art.