Abracadabra: the cabalistic title of the Tate’s latest grand exhibition also describes its new site on the Thames. For the first time ever last summer, the Millbank building merged all its galleries in a single space to present a “new artistic spirit” of optimism, fantasy and magic. This spring the Tate opens Bankside, an old power station on the other side of the river which the Swiss partnership Herzog & de Meuron has transfigured with the skill of a professional magician. But whereas the summer show indulged in the playful, humorous conjuring of pieces scattered on a purple kindergarten carpet, the work inaugurated on May 11 performs sorcery with the luminous rigor and severe dexterity of a surgeon: the mediocre industrial building has been transformed into an at once rough and sensual museum that receives the visitor into colossal spaces of concrete, glass and steel, while offering the Thames a brick prismatic mass transformed from humble pumpkin to magnificent carriage by the light beam crowning the station.

Herzog & de Meuron have enhanced the best part of Bankside’s old electric plant, which is its impressive scale: the light bar transforms what used to be a somber industrial pumpkin into a majestic carriage for art.

In competition with a New York MoMA soon to be extended and a Pompidou that has recently been remodeled, the Tate Gallery culminates – at Bankside – an expansion program which, besides enlarging the Millbank base with the Clore Gallery of the late James Stirling, led to the opening of branches in Liverpool and Cornwall. From now on the original site on the left bank of the Thames is to be known as Tate Britain and reserved for collections of British art, true to the national emphasis of the founder, Sir Henry Tate; whereas the new space in the power station of the right bank shall be called Tate Modern, and will bring together the institution’s collections of international art in the formidable volume in front of St. Paul’s Cathedral. With its 35,000 square meters built at a cost of £134 million (£50m financed by the National Lottery; as a term of comparison, the Dome has cost £897m, £538m paid for by the Lottery), the new Tate hopes to receive two million visitors yearly and presents itself as the last quarter-century’s most important British project in the arts field, one whose opening aspires to be as significant as the MoMA’s in the twenties and the Pompidou’s in the seventies.

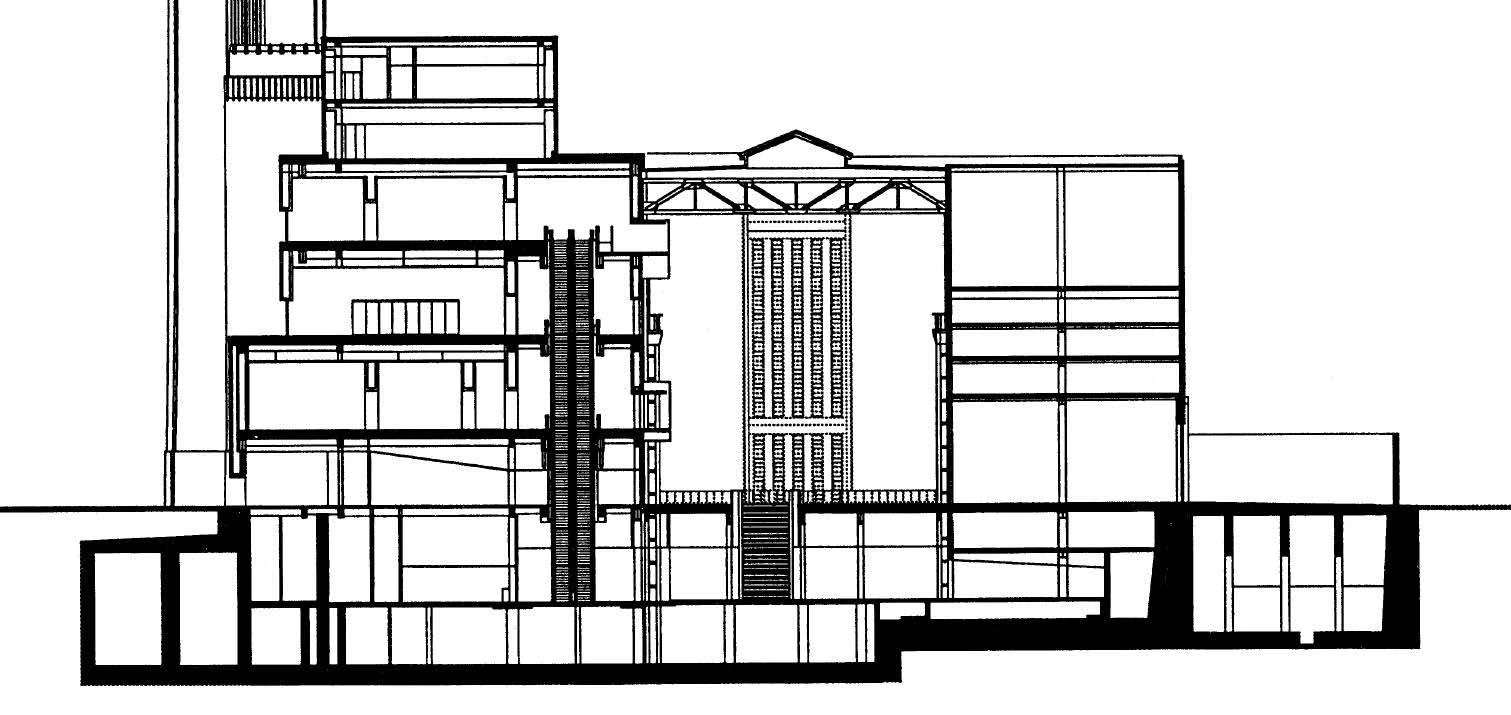

The enormous turbine hall is now a covered street, illuminated zenithally and by two translucent glass bars similar to that which tops the roof, while the galleries impress for their stark simplicity.

Inscribed within the framework of a Millennium London that is regenerating its monumental heart (through operations like the pedestrianization of Piccadilly and Trafalgar Square, the renovation of the British Museum or the enlargement of the Victoria & Albert) while refurbishing run-down zones on the banks of the Thames (threaded together by the extension of the tube’s Jubilee Line, which links downtown to the docks and the Greenwich dome), the Tate Modern will be the main engine for urban change in the Southwark district – where Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre has been faithfully reconstructed and is already functioning successfully. Well-connected thanks to a new underground railway station and a footbridge across the river, this quarter will benefit from the impact of a cultural package designed to revive an entire deteriorated area. Similar in this sense to the Pompidou, which was also meant to be a catalyst of urban regeneration, with its exceptional growth the Tate endeavors above all to attain the dimensions that would put it on par with the MoMA (a museum it has established close ties with, the first fruit being the launching of a joint enterprise of cultural e-commerce, which is expected to reap as much profit from virtual visitors as is currently obtained from physical visitors).

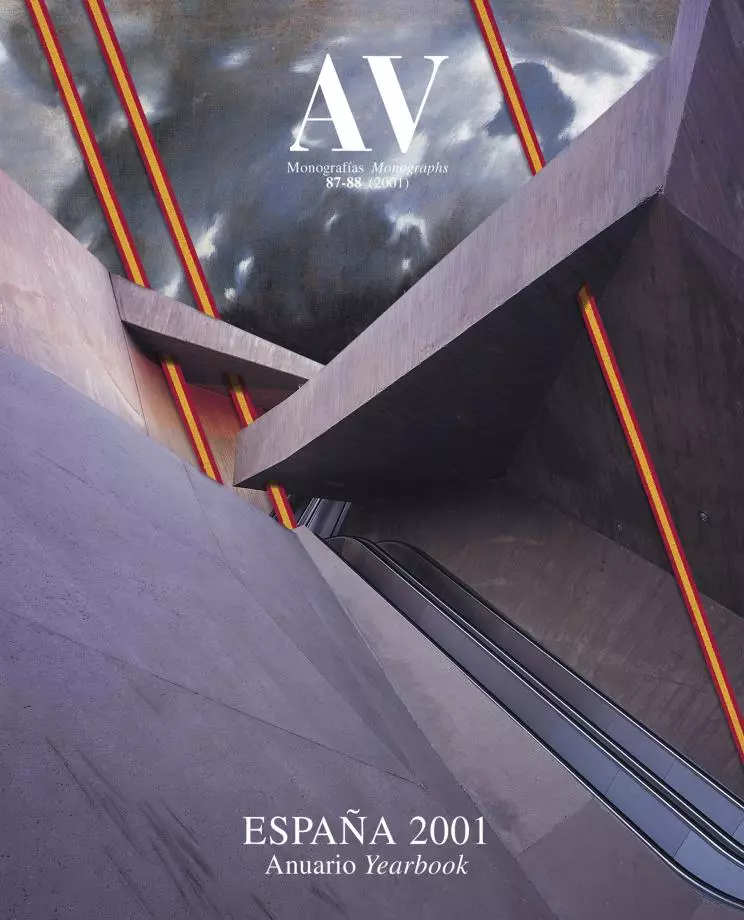

The huge scale and the privileged location of the building chosen for the extension are in tune with the extraordinary ambition of the museum project promoted by the Tate’s director, Sir Nicholas Serota, but the architectural quality of the power station completed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott in 1963 is far below the artistic goals of the institution. Lacking the surreal allure of Scott’s other power station on the Thames, Battersea, which raises its four chimneys shaped like classical columns as a solemn and smoky upturned table, and devoid, too, of the friendly charm of red telephone booths that are the architect’s finest legacy, the Bankside station is a colossal, brick-lined metal structure where Wright’s Maya period and Dudok’s Hilversum combine with the design of an Art Deco radio to present a facade that, if rather antiquated in the thirties, was an out-right archaism by the sixties. Joseph Rykwert calls Sir Giles and his contemporaries (Sir Reginald Blomfield, Sir Edwin Cooper, or Sir Herbert Baker) pompier architects, but not even this derogatory expression suffices to describe the strange fossillike presence of a brick scenography that erects in front of the dome of St. Paul’s a colossal, prismatic chimney on the axis of a feignedly symmetrical front.

It was this architectural dinosaur that the Swiss firm faced up to with strategic intelligence, capitalizing on the best of the building, namely its impressive size and the industrial roughness of its interior spaces, while transforming its image altogether through the superposition of a horizontal glass volume that shines at night and gets reflected in the dark waters of the Thames like a weightless geometric specter. The enormous turbine hall has been converted into a covered street 155 meters long, 23 wide and 35 high, naturally illuminated by skylights and artificially by two beams of translucent glass which are a translation of the roof’s dazzling crown, and which float between the heavy riveted supports and the cranebridge of the original building. Descending as a ramp from one of the side facades, this public street provides access to the auditorium, the coffee shop, the shops and the three floors of exhibition galleries, which take up the old boiler house and are topped by the glass beam, visible from outside, that accommodates the restaurant while serving to bring light into some of the exhibition spaces. The design of the galleries is surprisingly simple: rectangular rooms defined by white walls, flat ceilings with flush lights, and floors of dark concrete or rough, unvarnished oak boards where the iron grilles of the ventilation system are silhouetted with seeming nonchalance.

The complex thus takes on an air of refined brutality that stirs one’s emotions on account of its essential primitivism, very far from the sensationalism of the ‘dirty art’that has become the emblem of cool Britannia. Here nothing looks elaborated or superfluous, and while traversing the monastic rooms, the straightforward stairs or the laconic gardens it is hard to picture the meticulous Harry Gugger’s innumerable conflicts with the expedient British contractors (although the Swiss firm stresses the joint authorship of its four partners, Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron, Harry Gugger and Christine Binswanger, only Herzog and Gugger assumed direct responsibility for this commission); the crises sparked by the unique translucent glass panes of the turbine hall, which were manufactured in Spain, sandblasted in Austria, coated in Germany, and sent back to Austria for the fixings to be installed on them before finally being crated and shipped to their final destination in London; or Jacques Herzog and Nicholas Serota’s disagreements with Norman Foster with regard to the latter’s pedestrian bridge, whose south end interfered with the gardens that the Swiss landscape architects Kienast and Vogt had designed for the segment of the riverbank adjacent to the museum.

Everything contrived, difficult and abrasive about the project has evaporated in the final result, and in this distracted sublimation lies the magic of a transformation that has blown life into an ephemeral colossus, a power station that was in use for less than two decades and which now vibrates anew under the luminous energy of art. Using Carlos Santana’s lyrical formula, Herzog & de Meuron have joined “molecules and light”, but like the guitarist of Abraxas, at Bankside the architects have used no other talisman than a natural approach. The magic wand of their abracadabra has not been the mystery of the supernatural, but the strong, optimistic, smooth beauty of the super-natural.