Tate Modern, London

Herzog & de Meuron- Type Refurbishment Culture / Leisure Museum

- Date 1994 - 1999

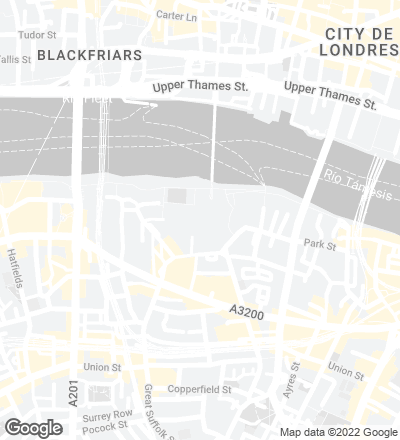

- City London

- Country United Kingdom

- Photograph Margherita Spiluttini Shinkenchiku Sha Peter Cook View

- Brand Arup

As part of a long term decentralization process, the Tate Gallery commissioned the renovation of its London headquarters in Millbank and its Liverpool site to James Stirling, its branch in St. Ives, Cornwall, to Evans and Shale, and will now move its collection of international contemporary art to Bankside in the capital of the country. An international competition, which the organizers admitted was used to find an architect more than a building, chose the studio’s project to turn the old electric power station by Gilbert Scott, also the designer of the famous red telephone boxes, into a gallery. Constructed in 1963 and in disuse since 1981, this industrial building faces St. Paul’s Cathedral from the southern bank of the River Thames, and will be the driving force for the regeneration of a central but rather forgotten area, which will be linked to the historical City by a pedestrian bridge designed by Norman Foster with the sculptor Anthony Caro.

The basic construction is a symmetrical brick composition formed by three parallel naves and a powerful central chimney which is being transformed using a ‘quasi-invisible’ strategy. The central bay, which formerly housed the turbine room, structures the visitors’ itinerary like a covered domestic mall aimed at being the first step in the recovery of the adjacent public spaces. This central void provides access to the coffee shop, the shop and the auditoriums. It will be used to exhibit the larger works, and will also be a place where visitors stroll and chat as they would in any other plaza. The main exhibition rooms, arranged on the top three levels to the left and right of this pivotal axis, unfold a wide variation in spaces.

The visible symbol of this silent metamorphosis is the skylight which counters the vertical dominance of the chimney on the river frontage, with a glazed envelope that announces the activity within the Gallery. Toplighting is fed into the museum through rectangular panels that filter both the natural light and the spotlights from the ceiling of each room. In accordance with the theories shared with Rémy Zaugg on exhibition spaces, the collection is shown in introspective environments that are interlinked by a circulation system that includes privileged views over London. From both the pavement terraces of the main body and the lookout at the top of the chimney, the new Tate Gallery faces the city like a bastion offering art to the general public...[+][+][+]

Client

Tate Gallery

Herzog & de Meuron Project Team

Partners: Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron, Harry Gugger (Partner in Charge), Christine Binswanger.

Project Team: Michael Casey (Associate, Project Architect). Thomas Baldauf, Christine Binswanger (Partner), Ed Burton, Victoria Castro, Peter Cookson, Irina Davidovici, Liam Dewar, Catherine Fierens, Hernan Fierro, Adam Firth, Matthias Gnehm, Nik Graber, Konstantin Karagiannis, Angelika Krestas, Patrik Linggi, José Ojeda Martos, Mario Meier, Filipa Mourao, Yvonne Rudolf, Juan Salgado, Vicky Thornton, Kristen Whittle, Camillo Zanardini, Emanuel Christ.

Planning

Associate Architect: Sheppard Robson + Partners; Landscape Design: Herzog & de Meuron in collaboration with Kienast Vogt + Partner; Construction Management: Schal International Management Ltd; Interior design: Herzog & de Meuron in collaboration with Office for design, Lumsden Design Partnership (Retail Consultant); Electrical Engineering: OAP-Ove Arup Partner; HVAC Engineering: OAP-Ove Arup Partner; Plumbing Engineering: OAP-Ove Arup Partner; Structural Engineering: OAP-Ove Arup Partner; Cost Consultant: Davis Langdon & Everest.

Consulting

Acoustics: OAP-Ove Arup Partner; Facade Engineering: Emmer + Pfenninger AG; Lighting: OAP-Ove Arup Partner; Built in Furniture: Herzog & de Meuron in collaboration with Jasper Morrison; Fit Out Manager: OAP-Ove Arup Partner; Furniture: Office for design: Jasper Morrison; Gallery and Garden Benches: Herzog & de Meuron with Mario Meier.

Contractors

General Contractor: Schal.

Photos

Margherita Spiluttini; Shinkenchiku Sha; Peter Cook / View