Sacred Places

The project by Renzo Piano in Ronchamp and the one by Frank Gehry in Jerusalem express in opposite ways the lasting conflict between the sacred and the profane.

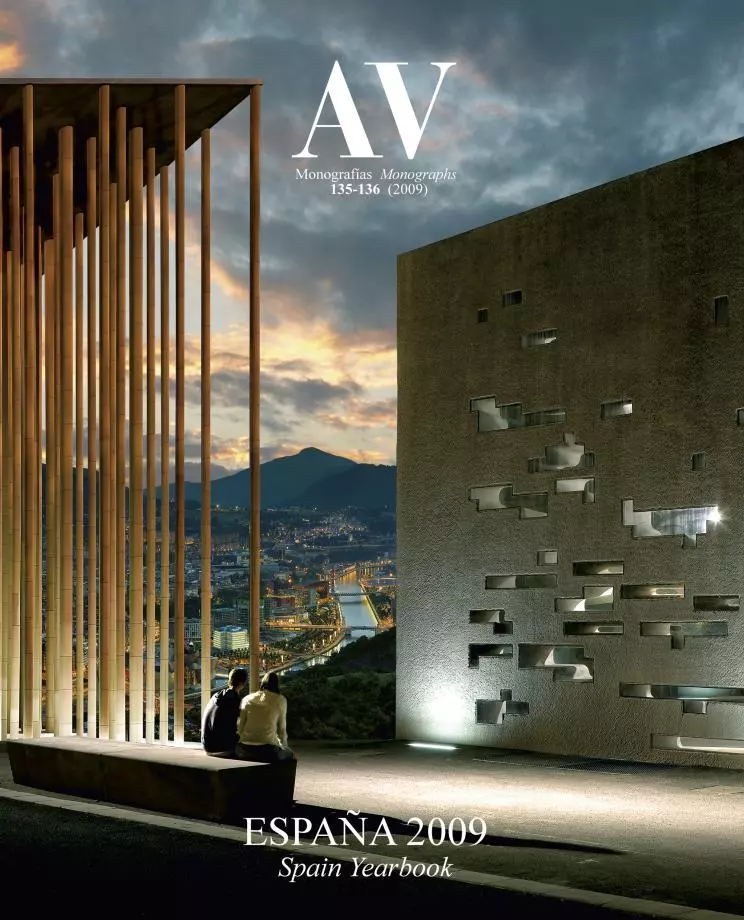

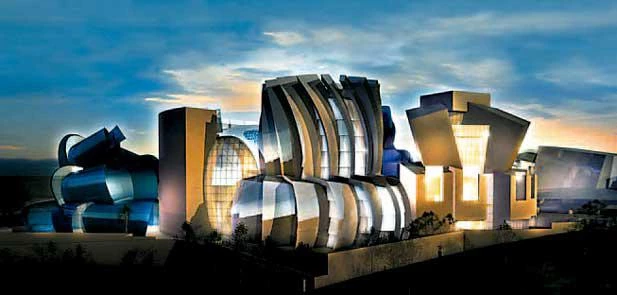

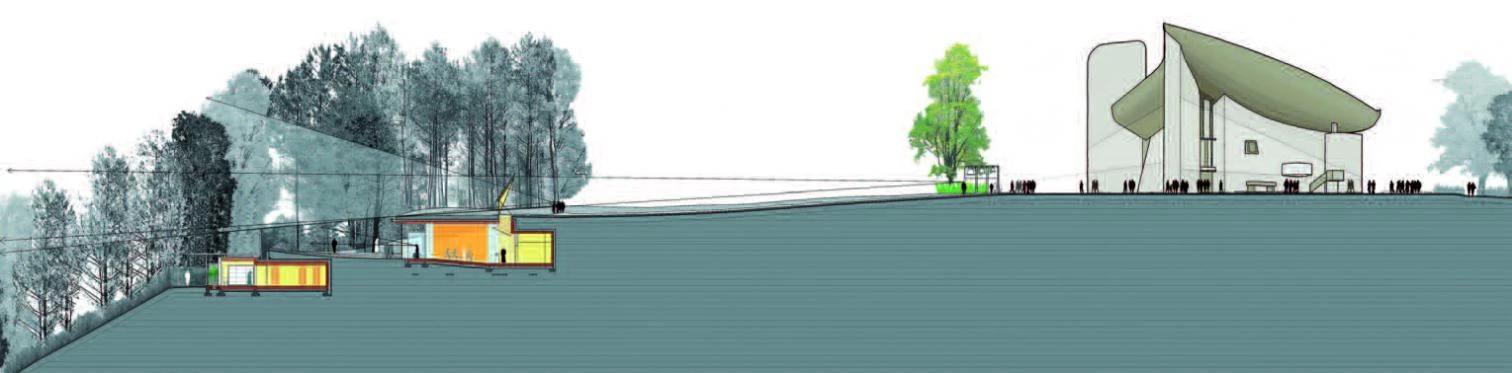

Expelled through the door, the sacred now Ereturns through the window. A small convent in Ronchamp and a large museum in Jerusalem illus-trate two opposed ways of resolving the conflict between the sacred and the profane in the contem-porary world. In the French town, a dialogue and negotiation process has allowed the Genoese Renzo Piano to start building a cluster of cells for Claris-sa nuns on the slope of the hill crowned by the Chapel of Notre-Dame-du-Haut, Le Corbusier’s most acclaimed work; in the heart of what is com-monly called the Holy Land, a judicial sentence will allow the Californian Frank Gehry to raise a huge complex funded by the Simon Wiesenthal Center –the famous hunter of Nazis, incidentally an archi-tect by profession – on the site of the city’s oldest Muslim cemetery. As much in Ronchamp as in Jerusalem, the formidable controversies sparked by the projects have dealt with landscape and heritage; nevertheless, in both cases these concerns have been pushed into the background by the heat of the symbolic and religious debate.

The stormy shapes of the Museum of Tolerance in Israel, to be built on the site of an old Palestinian cemetery, strike a contrast with the respectful profile of the small convent that will complete the chapel of Notre-Dame-du-Haut.

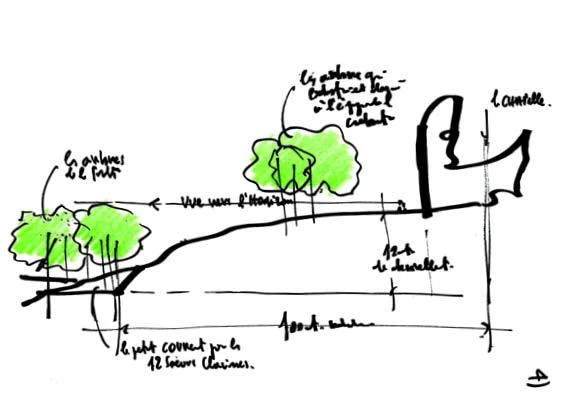

The pilgrimage chapel of Ronchamp rises on an old sacred site in the foothills of the Vosges; the grounds have been used to worship the sun, Roman gods and the Virgin Mary, but ever since Le Corbusier finished the sculptural volumes of this lyrical sanctuary, the only cult in force on the hill has been that of architecture. With this work the master changed his mechanistic and nautical language for an organic and terrestrial one, al-tering the course of this discipline and turning the site into a destination for artistic pilgrimage. Piano’s project, carried out in collaboration with the landscape designer Michel Corajoud, was drawn up on the request of Jean François Mathey and Dominique Claudius Petit, children of the chapel’s original clients, who now preside over the associations of Notre-Dame-du-Haut and Les Amis de Le Corbusier, but these credentials did not prevent strong opposition to the insertion of the convent in this mythical place.

La demolición de la cárcel de Carabanchel en Madrid hizo desaparecer un colosal edificio panóptico, y a la vez destruyó una oceánica colección de grafitis que se extendían desde las galerías radiales hasta la bóveda central.

Desde luego, los críticos del proyecto basaban su postura en la defensa de la obra de Le Corbusier, pero tanto el escaso impacto visual de la nueva cons-trucción —una docena de celdas excavadas que no se perciben desde la cumbre que ocupa la capilla—como la mejora del entorno que supone la prevista demolición del lamentable pabellón de acceso y la eliminación del aparcamiento asfaltado adjunto, hacen pensar que una motivación subyacente ha sido el procurar mantener el carácter secular y artístico de Notre-Dame-du-Haut, frente a una recu-peración confesional y religiosa del enclave. Paradójicamente, los oponentes de Piano defendían la naturaleza sagrada de la colina, pero a condición de que la única devoción practicada allí fuese la del arte, y a su vez muchos de los partidarios de la intervención parecían tener más en cuenta la recuperación de la cota para el culto católico que la deseada rehabilitación del emplazamiento.

Gehry’s museum in Jerusalem, in turn, places a still-life of huge fruit slices on a Muslim cemetery west of the old city walls, and has caused expectable indignation among Israeli Arabs and Palestinians. Ironically named the Museum of Tolerance, this extravagant cluster of waves and curls, flakes and fins, bubbles and explosions, is something more than the folly of an almost octogenarian Jewish architect who aspires to leave his mark in the Promised Land through a gigantic and shaken still-life of fragments: this titanic and trivial tray, packed with peelings and shavings, is an aggression on sacred tradition and archaeological memory, and a ges-ture that imposes the secular values of spectacle and authorship on an archaic and perhaps also obsolete environment. Although in appearance it is an affirmation of lay and artistic modernity, expressing tolerance through the chance juxtaposition of forms, the museum is really more an episode of religious war and territorial conflict in a place where, as has so often been said, there is too much history for so little geography.

The artist Miquel Barceló transformed the dome of the main conference hall of the United Nations headquarters in Geneva spraying paint on a relief of stalactites that evokes the amniotic atmosphere of a submarine world.

Of late we have seen an unexpected worsening of the conflicts that bring together architecture and religion, from the fight between Thailand and Cambodia for the ruins of the Preah Vihear Temple to the struggle for the Serbian monasteries of Kosovo, passing through the innumerable controversies that have been sparked by the building of mosques in Germany, France or Great Britain. The period of history begun by September 11 is often perceived in the light of religious or cultural fractures, however much the rhetorical Alliance of Civilizations that can now be visualized in Geneva under Miquel Barceló’s aquatic and stalactitic dome – which par-adoxically coincided in time with the demolition of the dome of Madrid’s Carabanchel prison, a panoptic and penitentiary Utopia which neglect had turned into a wild temple of graffiti, its walls vibrating with a violent and gratuitous truth that is absent in the onerous and oneiric cave of the Majorcan artist – tries to smoothen the edges of the conflict in the amniotic and chromatic magma of diversity. Even more important, this landscape crackled by fissures is opening up a gap between the secular organization of society and the pugnacious return of faith as political theology.

Perhaps, as Mark Lilla maintains in The Still-born God, “the twilight of the idols has been post-poned”, and we are condemned to go back to waging the wars of the 16th century. Meanwhile, we must reclaim for art the spiritual domain of transcendence – even at the risk of adoring a new ‘golden calf’à la Damien Hirst – and at all costs prevent that place of devotion from polluting the territory of civil politics. Renzo Piano, who long ago built a museum in Houston that was understood as a sanc-tuary for the Catholic patron of the arts and intellectual Dominique de Menil – and later a chapel for the work of Cy Twombly, in the wake of the Rothko chapel –, has in Ronchamp been able to establish an intelligent dialogue with its critics, modify his project partly, and come up with a ‘peaceful’ solution that reconciles the Clarissa nuns with Le Corbusier. Frank Gehry, who unlike the Italian feels more like an artist than a builder, has placed his by now already jaded sculptural talent at the service of a clearly political endeavor, imposing himself on his critics by judicial means and using his shaken forms more like a throwing weapon than like a terrain of negotiation. In the final analysis, the builder who establishes a politi-cal dialogue is the true artist, whereas the artist who imposes himself in the courts seems little more than a partisan politician: there will be more sacred emotion and civil dignity on the hill of Ronchamp than in the Museum of Tolerance in Jerusalem.[+][+][+]