July was November, and it snowed in the summer. With the dreaded deaths of Miralles and Oíza, Barcelona lost a son, Madrid a father, and Spain two disproportionate architects who now inhabit the frosty territory of history. We learned of the disappearance of Enric Miralles at midday, and that of Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza shortly before midnight, a time difference that symbolises the diversity of the loss and the distance that separates a journey that is too long from a career that has been completed: at 45, the Catalan left us at the zenith of his fractured orbit of life; at 81, the Navarrese left the scene at the end of his biographical representation. Therefore, if Miralles remains in the emotion like an open and bleeding wound in the heart of the day, Oíza closes the long furrow of his journey with the cushioned pain of a cauterized lesion from the twilight. In his farewell, both have been accompanied by poets: on 3 July, Miralles died in Sant Feliu de Codines while John Hejduk, an architect whose most valuable legacy is his hermetic drawings and his books of poetry and fables, died in New York; and a fortnight later, on 18 July, Oíza died in Madrid while José Ángel Valente, the most ineffable voice of contemporary Spanish poetry, died in Geneva. It is also an appropriate coincidence, because if Miralles' plans and texts vibrate with the same calligraphic and lyrical intensity as some of Hejduk's sketches and stories, Oíza's prophetic and paradoxical verb burns in a dark light that is not unaware of the transcendent and visionary brilliance of so many of Valente's writings.

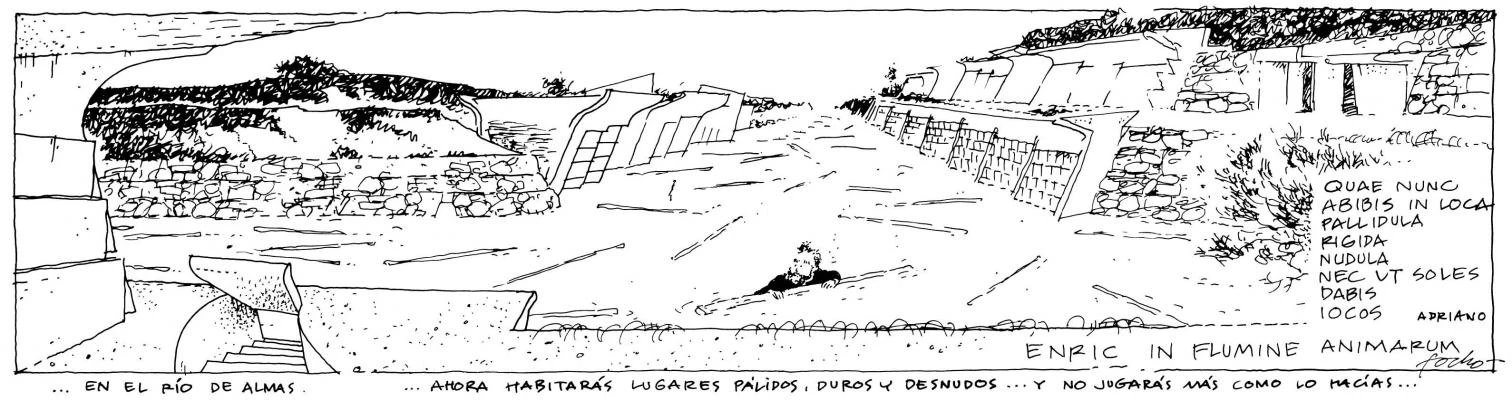

The Catalan Enric Miralles died at the zenith of his career, at the age of 45, and his remains rest in the Igualada cemetery, a magical concrete landscape that will survive in the 20th century canon as his best work.

Miralles was not only the most gifted architect of his generation; he was artistic creation in its purest form. From his letters in the form of calligrams to the unusual napkins of a domestic lunch, everything about him and his life transmitted a sensation of luminous ease and exact imagination that crystallised into objects or strokes of prodigious harmony. Nourished by a vast and dispersed visual culture, and moved by a seemingly inexhaustible energy, Miralles created a formal universe of such extraordinary originality and beauty that it will remain an unfading legacy. From my dazzled admiration, I occasionally reproached him for his functional discouragement and constructive adventurism, warning him that this attitude could lead him to have more past than future; he did not like my criticism, and for a while he signed his faxes with a sore "Enric, the one who has more past than future". But that giant had a broad back, and when I saw him playing basketball with his Harvard students at the end of an exhausting day of judging, I could not imagine that anything could break his muscular determination. Cancer did it, and so suddenly and violently that it is still hard to think of him dead. "I don't know if I've written to you, but I've thought about you many times," he said in his last fax, describing his life in Houston with his wife Benedetta, his two children and his mother, announcing his forthcoming return to Spain and expressing his "amazement at the human values, the affection".

He exchanged Robert Stern's Texan house, which had been lent to him by the developer Gerald Hines, for another belonging to José Antonio Coderch in a village near Barcelona, but fate would only grant him two weeks there. We buried him in his cemetery in Igualada, a magical concrete landscape whose project he won in a competition at the age of 30 with his first wife, Carme Pinós, and which will surely survive in the canon of architecture of this century that ends up as his best work. Unfinished and as brilliant as his own life, no architect will have a final scenario of greater pathos, poetry and emotion. Moved by the simultaneous death of Miralles and Hejduk, Peter Eisenman calls me to explain his project for a posthumous tribute to his American colleague, with whom his own biography - from the New York Five to the Cooper Union - was so intimately entwined: If Fraga does not object, he will erect in his City of Culture in Galicia the two towers that Hejduk did not manage to build in the Belvís Park in Compostela, and the stone topography of that monumental and symbolic mountain will have two new glass and granite pilgrimage landmarks. In the case of Miralles, it is possible that the final tributes also refer to unfinished projects, from the Scottish Parliament to the headquarters of Gas Natural the Santa Caterina market in Barcelona. It is difficult to know how many of these will be brought to fruition, and how many will be ruined by the misguided example of Gaudí's Sagrada Familia; but Miralles' unique place in history will not be affected by these vicissitudes.

The Navarrese Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza died at the age of 81; his passionate curiosity led him to travel many roads and left a vast legacy, including works from his youth such as the Basilica of Aránzazu.

In comparison to the mythical drama of a premature death, fully lived biographies fade in the pale panorama of habit. Oíza was the grand master of us all, but his octogenarian disapperance varnishes this figure with the subdued shine of normal life. He died at almost the same age as Eladio Dieste, the great Uruguayan engineer who quit the scene the next day in Montevideo: two exits that can only be considered early if compared with those of the two recently deceased grand dames of architecture, namely Charlotte Perriand, furniture designer and collaborator of Le Corbusier, who departed at 96, and Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, author of the Frankfurt kitchen, who was five days short of turning 103. Hejduk and Valente were 71, not an age we ordinarily associate with an unfinished oeuvre.

As for Oíza, his death was preceded by a protracted withdrawal from the scene which had us all prepared. The melancholy of his final going then brings to mind the passionate personality of an architect of pyrotechnic intelligence and infinite curiosity, one with the capacity to drink from all fountainheads and who was denied the international recognition he deserved only because of such stylistic dispersion, a denial nevertheless compensated for by his volcanic and polemic popularity within Spain. He was a charismatic professor at the Madrid school, master of architects like Rafael Moneo, and I had the privilege of sharing with him the same classrooms, and of coinciding with him on several juries where his heated word would turn into discreet indecision. He would become himself again over lunch, where he delighted us with his penchant for paradoxes and geometric enigmas. In the Madrid of the fifties he built admirable social housing quarters, and two emblematic towers that remain as symbols of the formal interests of the sixties on one hand, and the fascination for technology of the seventies on the other, Torres Blancas and the Banco de Bilbao, culminating his career in the eighties with the ruedo on the edge of the M-30 highway, a colossal complex of apartments that reunites Rossi to Venturi, and which merges his investigations in the residential typology with his passion for monumentality in a synchretic work that was the most widely debated of his long career. But at the moment of farewell I prefer to recall a project he carried out at barely 30 – the age Miralles was at the time of the Igualada competition – and in the course of which he met María Felisa, now his widow, and the sculptor Jorge Oteiza, for whose future museum he conceived his posthumous project, currently on display as a model at the Venice Biennale. I am referring to the Basilica of Our Lady of Aránzazu in the Basque country, an inverted ship of stone and wood protected by towers of almost ancestral violence, and which lodges in its whale’s belly the promise of resurrection represented by Jonas. Before Miralles’grave at Igualada Cemetery is a landscape of concrete tombstones partly lifted by an interior wind that transmits an identical message of hope, and such tenacity of the spirit may well be the best legacy of these two immortal architects.