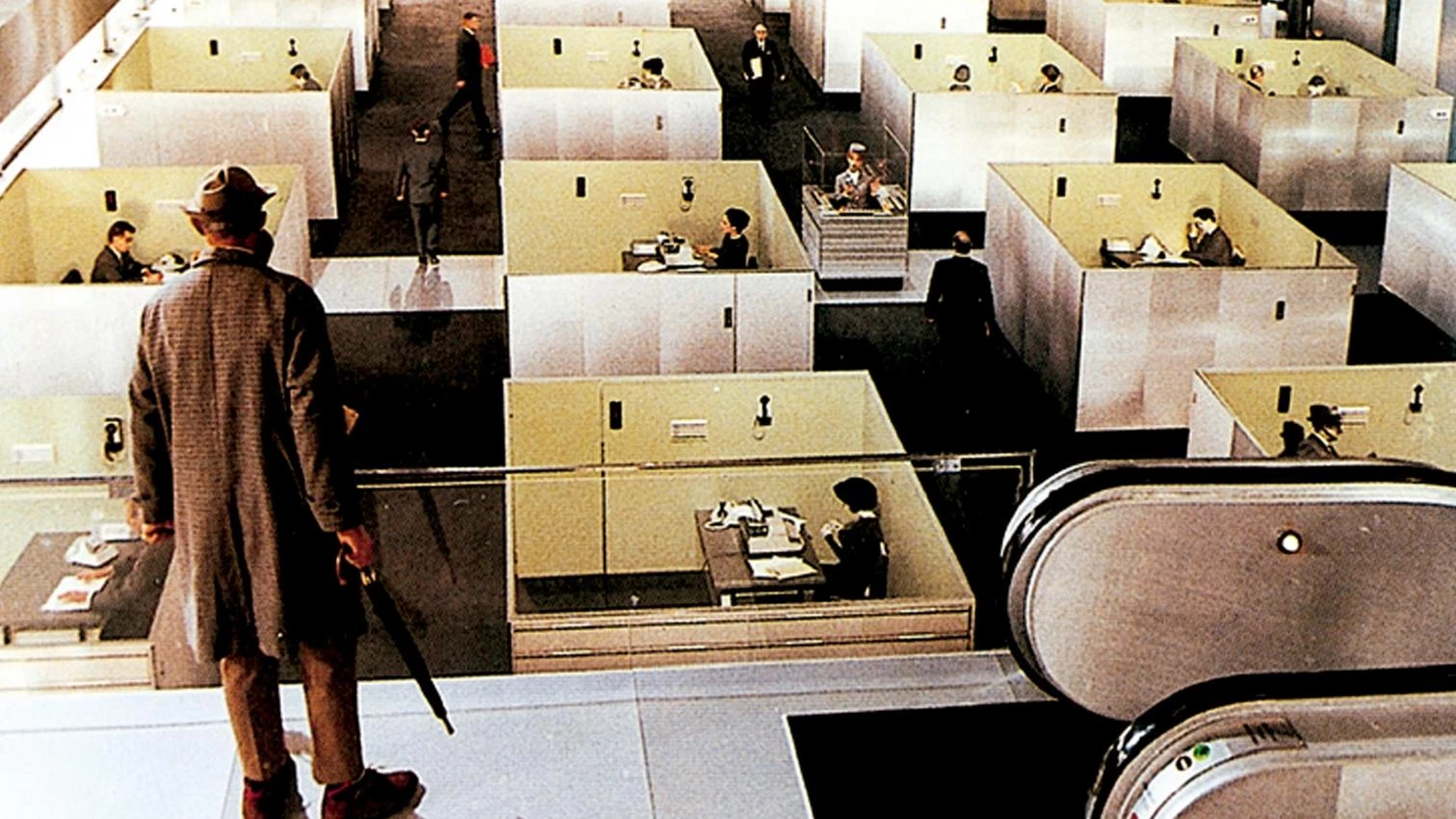

Life is an office, but the office is not life. Western adults spend half of their conscious existence in administrative environments of a hardly stimulating quality: if initiative is numbed in homogeneous space, the senses are dulled under the light without shadows of an artificial sky. In the 20th century, the rationalization of bureaucratic work was carried out by grafting onto the disciplinary panopticon of the Enlightenment the mechanical organization of tasks proposed by the scientific management, and that hypostatic union of Jeremy Bentham and Frederick Taylor produced offices to process paper with the effectiveness of mass production in assembly lines. A hundred years ago now, Wright’s Larkin building forebodingly materialized the revolution in the making, and the administrative homotopy would from then on be object of bitter or friendly satires, from the Billy Wilder of The Apartment and its famous set of a never-ending office, to the Jacques Tati of Playtime and the perplexity of Monsieur Hulot before the tidy labyrinth of corporate offices.

Before these extreme expressions of architectural anomy, the reformers tried out several alternatives: the picturesque German Bürolandschaft expanded quickly, but the variety of its landscape devices barely altered the pathology of deep floor plans; the fragmentation of Dutch structuralism attempted to recover domestic scale and appropriation of workplaces, but that anthropological humanism turned out to be incompatible with the ever changing structure of businesses; and the fanciful scenography of Californian deconstruction has attempted to shape a playful utopia, but the anti-authoritarian mythology of those colorful kindergartens has failed to catch on outside the world of advertising agencies and the media. In spite of the wishful fantasies about the dissolution of the office prompted by cellphones and laptops, the best portrait of contemporary workspaces can still be found in the hypnotic photographs of Andreas Gursky: the nomadic office may have colonized the house or the airplane, but it has not eroded the extended hypertrophy of order.

Paradoxically, the uniformity of administrative space has had to coexist with the heterogeneity of its packaging, which has put stylistic resources at the service of business differentiation, reducing architecture to a communication and marketing device. Meanwhile, the main dilemma of corporations continues to lie between the urban skyscraper and the suburban groundscraper, and the final choice is determined as much by accessibility and safety as by ideological and symbolic reasons: there are office parks conceived as holiday resorts and others resembling military camps; there are social democratic skyscrapers that place leisure areas for their employees at the top, and neoliberal high-rises crowned by the private offices of plutocrats. However, all of them sharply contrast with the fertile and flexible fabric of the small and medium-sized offices that mixed with shops and houses make the city a living organism: this enterprising and resilient tapestry contains the best offices, vital centers of innovation and experiment which make more bearable the stubborn craft of living.