Aznar promises to promote the trademark España. But if the ballot bends in his favor, then as of tomorrow he will have to turn his attention to the Marca Hispánica, for it is in this borderline territory freed from Carolingian protection by Catalan counts that he should find the votes needed for his actual investiture, reconciling the global spirit of Madrid with the nationalistic reticence of Barcelona. At the start of the nineties, the leaning KIO towers became Madrid’s architectural representation of hot money; at the threshold of another decade, the sculptural tower of Gas Natural may come to be Barcelona’s emblem for the mediatic economy and for an urbanism that refuses to bend to the flows of stateless capital.

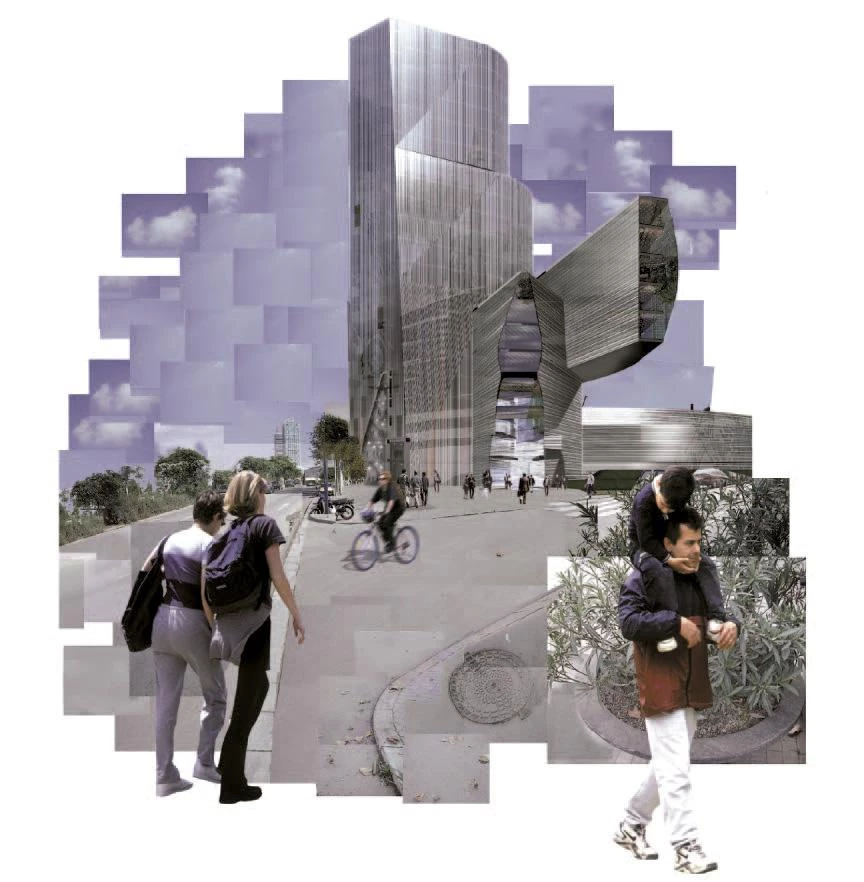

The lyrical expressionism and gestual force of the tower with which Miralles & Tagliabue won the competition to build the new headquarters of Gas Natural may turn it into a Barcelona symbol of the new economy.

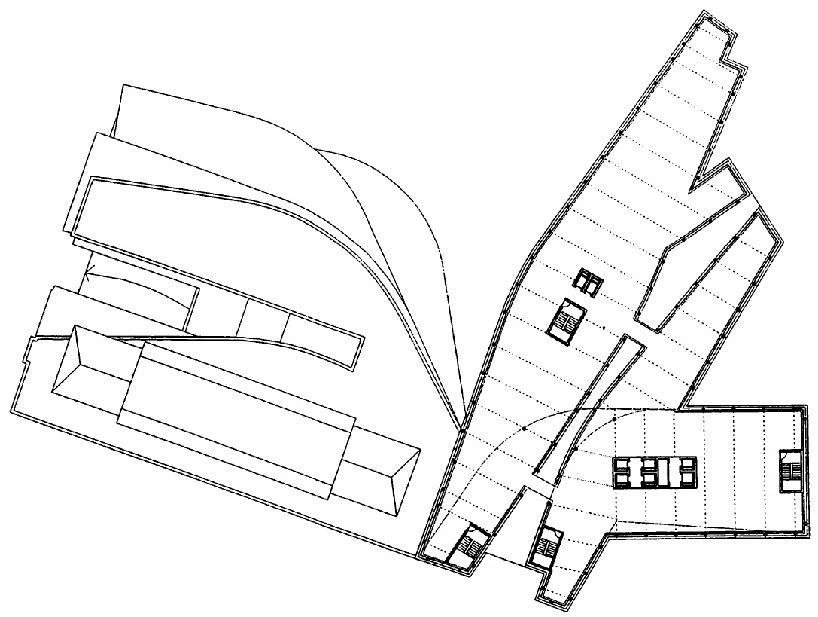

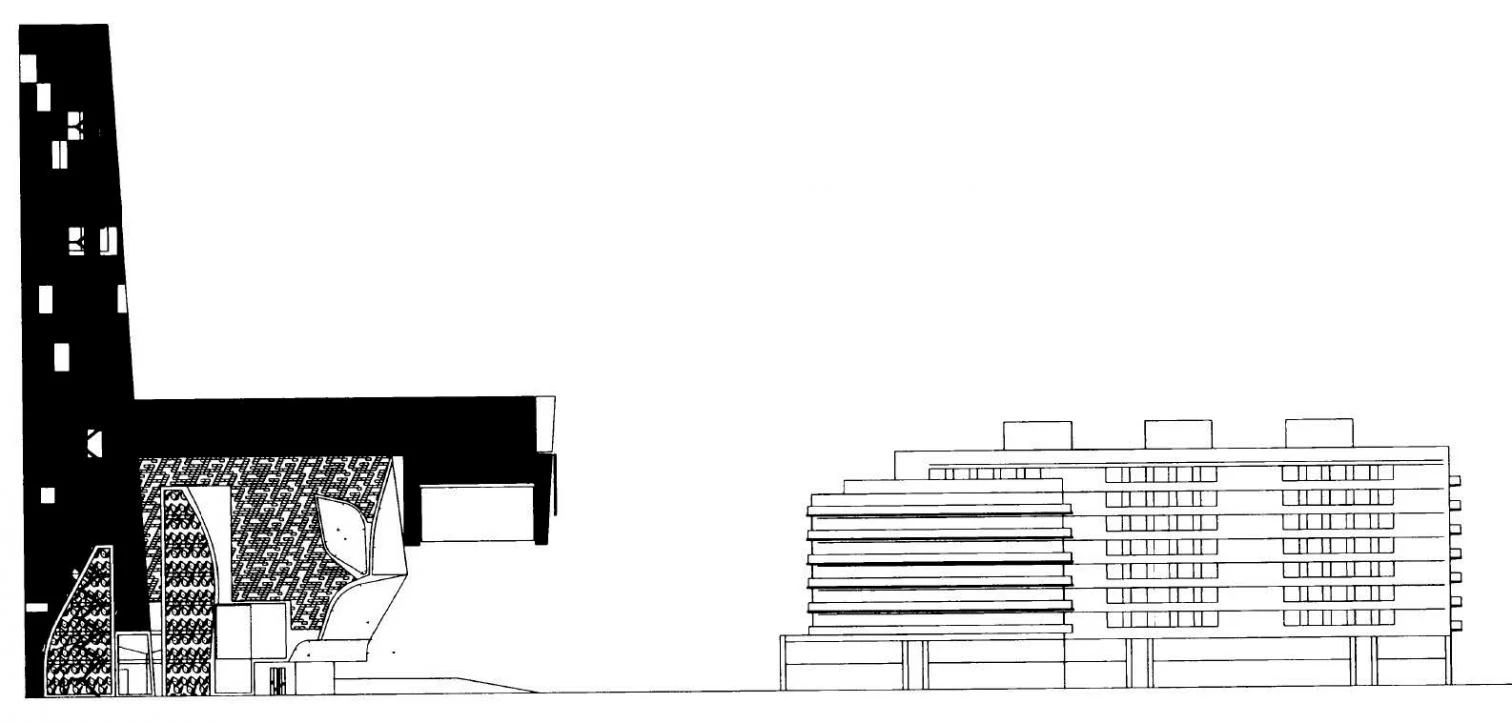

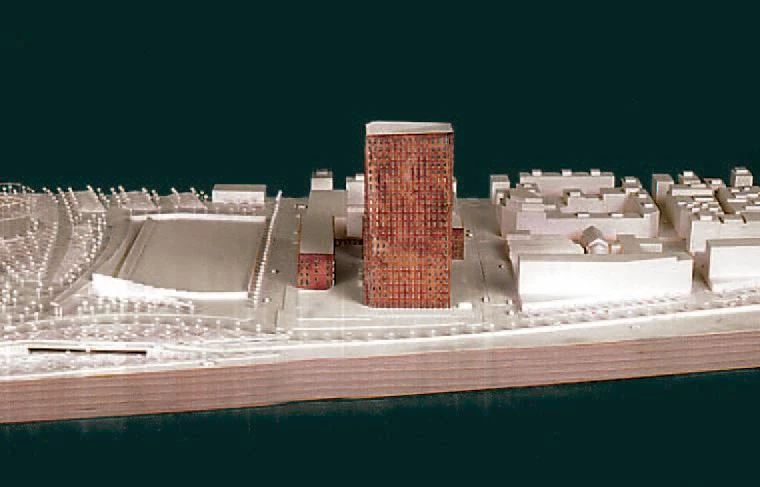

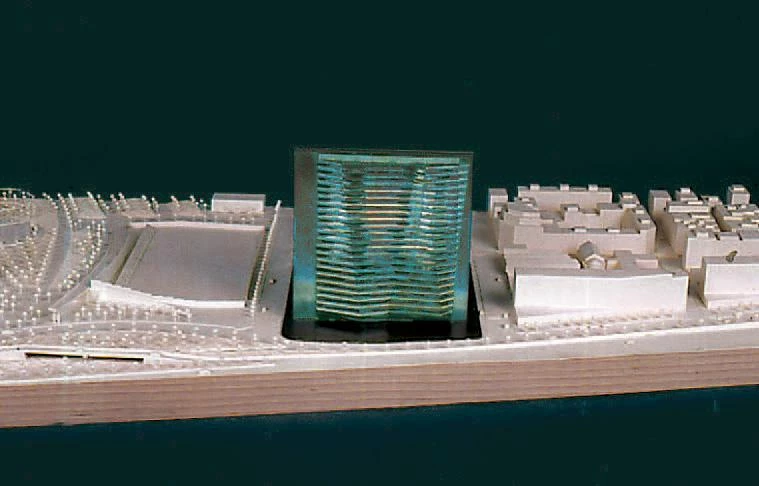

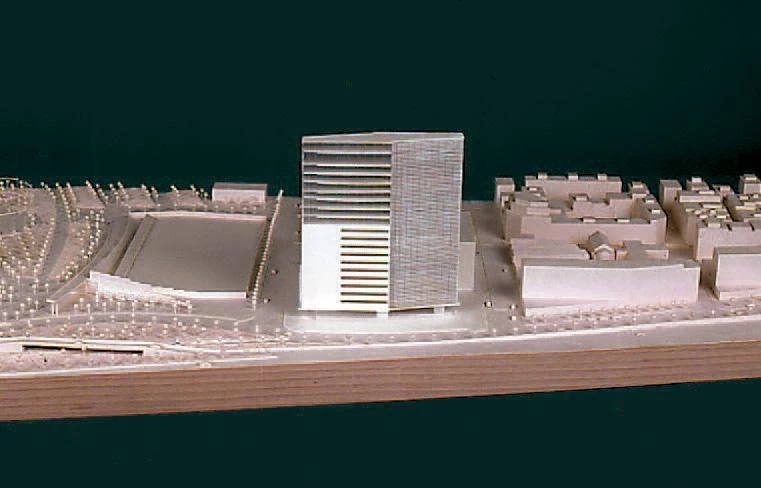

The new headquarters of Catalonia’s leading company is to rise on the edge of the Barceloneta, beside the coastal road belt and along the urban axis that connects the Gracia quarter to the sea through the Arch of Triumph and the Parque de la Ciudadela, on the site of the original gas plant now in a strategic position on one side of the Olympic Village. After negotiations withTown Hall that made it possible to build the 26,000 square meters of the project, those in charge of high-rise construction demanded the holding of an ideas competition, which the company duly convoked at the end of July of 1999 among eight architectural teams of the city. In November, a jury likewise composed of only Barcelonese members selected two finalists, the ironic and festive scheme with flaccid rows of windows of Martínez Lapeña & Torres, and the project of Miralles & Tagliabue. Because of their barrier-like nature, which blocked the visual relationship between the city and the sea, the jury ruled against Ferrater’s elegant folding screen and Espinet & Ubach’s refined striped curtain, as well as Brullet & de Luna’s slender block. Also deemed inadequate were the fragmented projects of Llinás and MBM, and not emblematic enough proved the proposal submitted by Henry. Finally, in mid-February Gas Natural decided on the design of Enric Miralles and Benedetta Tagliabue, presenting the winning project to the public in the presence of the mayor, as befits a corporate headquarters aspiring as well to be a symbol of the city.

Reminiscent of El Lissitzky’s Cloud-hangers or the anvils of Haus-Rucker-Co, this tower brings the formal unrest that Bilbao’s Guggenheim made a must for cultural buildings into the realm of corporate identity.

The twenty-floor tower of Miralles was de-scribed by the jury as “an amalgam of stepped and cantilevered structures,” and by Miralles himself as a “unique building...in the city’s silhouette” that tries to adapt to the different scales of the sur roundings by “fragmenting itself into a series of constructions that eventually form a unitary volume.” Both descriptions are precise, but hardly express the gestural force of this sculptural piece that flaps its wings with violence over the placid profile of the sea horizon and the horizontal Barceloneta. At a short distance from the two skyscrapers of the Olympic Village and substantially smaller, Miralles’ tower measures up to them visually thanks to the lyrical expressionism of its volumes, which reaches paroxysmal heights with the structural feat of a six-story appendage that juts out horizontally in a 40-meter cantilever 20 meters above the ground, fondly nicknamed the aircraft carrier by the project engineer, Julio Martínez Calzón, one of Spain’s finest specialists.

Evoking other visionary projects, from the ‘Cloud-hanger’ of the Russian El Lissitzky in the twenties to the colossal anvils of the Austrians of Haus-Rucker-Co in the sixties, the Gas Natural headquarters – flapping a single massive wing with the indifferent lightness of the firm logo’s lepidopteran – brings to the world of corporate identity the agitated language that the Bilbao Guggenheim has made a must in the exhibitionistic world of cultural buildings, but which was rare in the field of large companies. Although the museum’s architect, Frank Gehry, has built office buildings with dancing forms, not even his latest work in Düsseldorf – three trembling flans lined, respectively, with brick, plaster and steel, promoted by an advertising agency and which boast being the city’s most expensive office spaces for rent – comes close to the formidable scale, urban protagonism and structural audacity of this spectacular and sculptural construction sure to become a landmark in Barcelona’s geography and Miralles’ biography.

The process leading to this unexpected impact – steered from within the ranks of Gas Natural by Antoni Flos, an economist acquainted with town planning who held a high position in the Defense Ministry under both Narcis Serra and Julián García Vargas – also has a political interpretation. Gas Natural, formed by the fusion of Catalana de Gas and Gas Madrid, is a company that takes pride in reconciling its Catalanness with a bicephalous condition, and which obtained monopoly in gas distribution in 1994 when it took over the state-owned Empresa Nacional de Gas (Enagás), in a controversial operation that resulted from pacts between the socialists and the Catalan nationalists after the 1993 general election. La Caixa, the Catalan savings bank which managed it, and Repsol, the Spanish company that was the main shareholder, came to an agreement in January by which Repsol YPF would absorb and take full control of Gas Natural. Then the retrospective scandal of the privatization of Enagás broke out at the close of February, provoking the conflict between the present conservative government and the previous socialist managers, leading to José María Aznar’s electoral promise to end the monopoly on gas.

Participants and jury: all of the partakers in the competition organized by Gas Natural were from Barcelona, and the remaining proposals submitted ranged between geometric rigor and festive irony.

In the intricate tangle of privatizations without liberalization, mergers and acquisitions, crossed participations and business alliances that are tracing the new limits of power and money, only corporate headquarters remain to mark territories. Hence the skirmishes with Villalonga when he threatens to transfer Telefónica’s main offices to Miami, the clash with Ybarra when he decides to keep BBV’s in Bilbao after merging with Argentaria, or Repsol’s own decision to buy the Argentine firm Yacimientos Petrolíferos when it looks like shuffling of stocks might raise questions about where head offices should be. In this sense, the concession on the part of Gas Natural to build in Barcelona an emblematic headquarters for what as of January is but a piece of a large group – a strategic one nevertheless, considering the announcement that the future of Repsol YPF depends on gas and the electrical generation that uses it as fuel – constitutes a rare gesture of generosity that can only be understood from the perspective of our Marca Hispánica’s stubborn resistance to seeing its identity diluted in a world of trademarks without territory and territories without trademarks, a world where the trademark España is but an electoral fiction.

Martínez Lapeña y Torres

Carlos Ferrater

Espinet y Ubach

Brullet y De Luna

Josep Llinás

Martorell, Bohigas y Mackay