Asia on One Hand, Europe on the Other

Absent from the competition for New York’s Ground Zero, symbolic heart of America, Koolhaas designs a landmark for Asia and a new identity for Europe.

And New York in the distance. The results of the Ground Zero competition were announced on 27 February, and the next day The New York Times graciously divided its front page between a picture of an ecstatic Daniel Libeskind beside the model of his project and the last news about the preparations for war in Iraq. In the same issue of the daily, a full page ad paid by an American physician and scientist recalled the 70th anniversary of the Reichstag burning, expressing the fear that 9/11 could have sparked a similar effect: the transformation of a technically and culturally advanced democracy into an authoritarian and militaristic regime. Three weeks later, the US invasion of Iraq marked a turning point in contemporary history, opening a sea of discord between the US government, European public opinion, and Asian interests. One cannot help thinking that the planet’s current disorder was triggered by the destruction of the World Trade Center, nor judging the reconstruction of the Twin Towers in the context of the United States of America wagging its bellicose imperial muscle at its old partners in Europe and its new competitors in Asia.

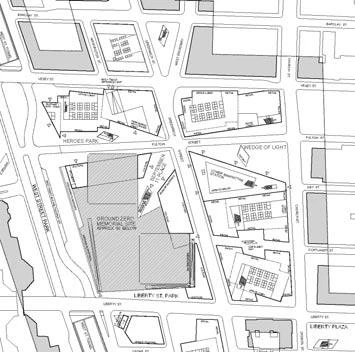

The winning proposal of Libeskind for Ground Zero (above) has raised as much controversy as the prior debate on how and with what to rebuild the void.

The so-called “commission of the century” fell upon a Polish Jew who is an American citizen and a Berlin resident, after a fierce debate that had Herbert Muschamp as its most abrasive protagonist. The architectural critic of the NYT lambasted Libeskind’s project as demagogic, kitsch, and agressive, “a war memorial to a looming conflict that has scarcely begun,” against the pacific idealism of its rival in the final round, the project of the group THINK (contemptuously called “a couple of skeletons” by Libeskind). In defense of the winning proposal rose Ada Louise Huxtable, architectural critic of The Wall Street Journal (a newspaper that those days was emphatically warning its readers about the danger that a larger and stronger Europe would pose for the United States), who lauded the ritual and commemorative archaism of the Park of Heroes and the Wedge of Light, the two public elements of this “architecture of memory” that provoked ap-plause and tears when presented to the public; Robert Ivy, editor of Architectural Record, who urged the NYT to hire another architectural critic; and Nina Libeskind, the architect’s wife and partner, who after Muschamp’s censures told a reporter that she “would’ve killed the guy on the spot.” European critics for their part have dismissed the project as commercial, superficial, and populist. Some would have preferred the grid of towers envisioned by Eisenman et al.; others, the monumental sheafs of the team of the Spaniard Zaera; many, the “endless columns” of Foster with Anish Kapoor, a simultaneous tribute to Fuller and Brancusi; and all have deplored the absence of Rem Koolhaas, leading interpreter of the spirit of Manhattan since his Delirious New York of 1978.

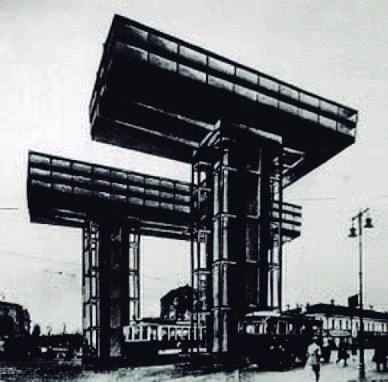

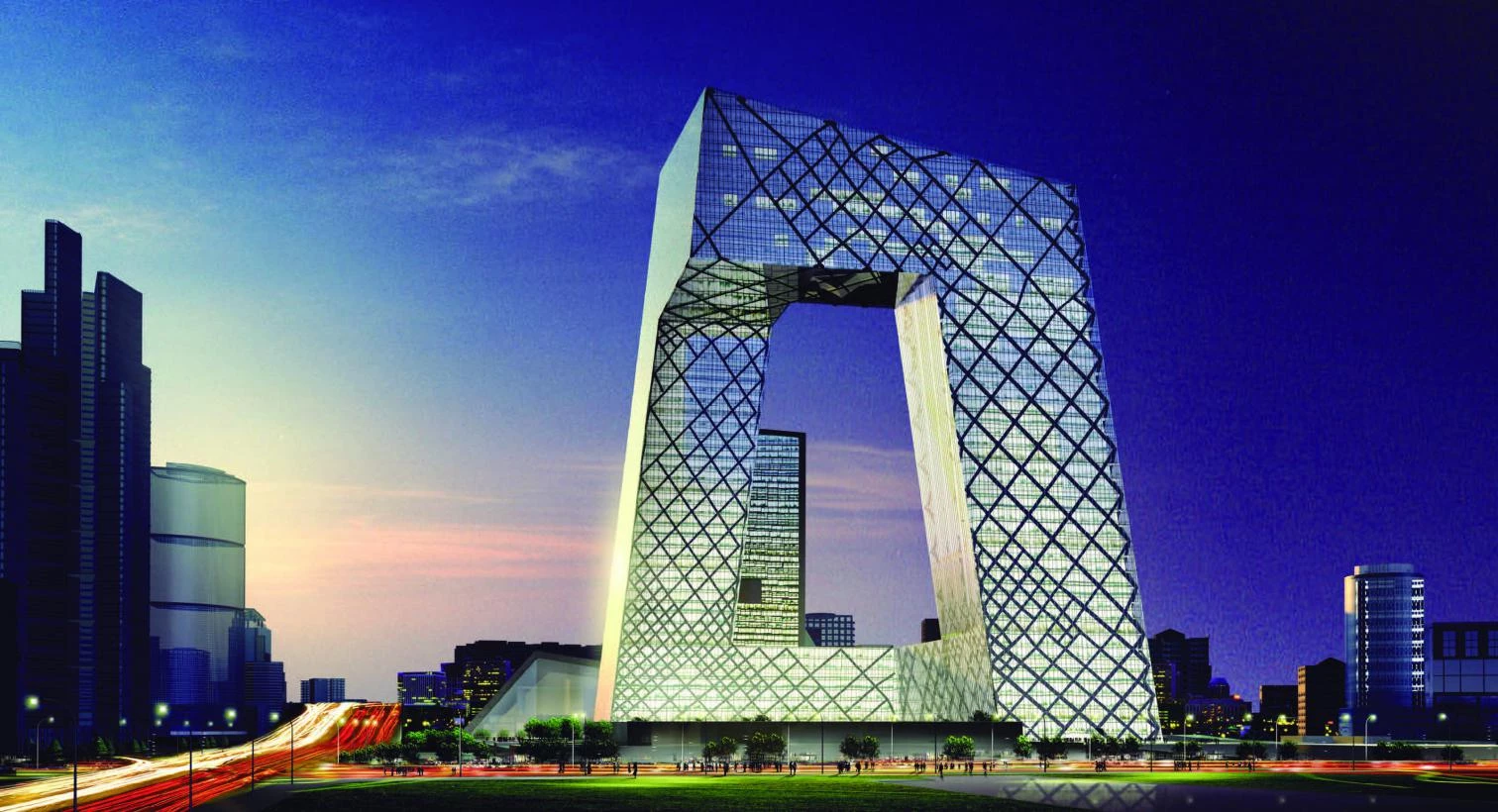

Koolhaas’ fascination for America has given way to his interest in China. With a loop-shaped skyscraper (right) which evokes El Lissitzky’s Cloud-hanger (left) he carried the competition for CCTV headquarters in Beijing.

The Dutch architect has long been considered the best representative of “Americanism,” the fas-cination of the European avant-garde for the care-free audacity of American construction, of which the skyscraper is the paradigm. But the author of S,M,L,XL has also succumbed to the passion of the Russians, from his youthful fixation with Leonidov to his adult interest in the tenacious stability of the communist regime; to a curiosity about Africans, singularly expressed by his explorations of the spontaneous inventiveness that ensures the survival of chaotic metropolises like Lagos; and to the generalized awe at the muscular vitality of Asia’s Pacific Rim, whose brutal and vulgar growth he described with admiring ambiguity in his work about the Pearl River Delta. And now it is the same hermetic and titanic China that lets him participate in the debate generated by the Ground Zero proposals with a huge building in Beijing, a 550,000 m2, 600 million euro project that won an international competition and whose emblematic value for the Asian colossus is comparable to that of the new World Trade Center for Americans.

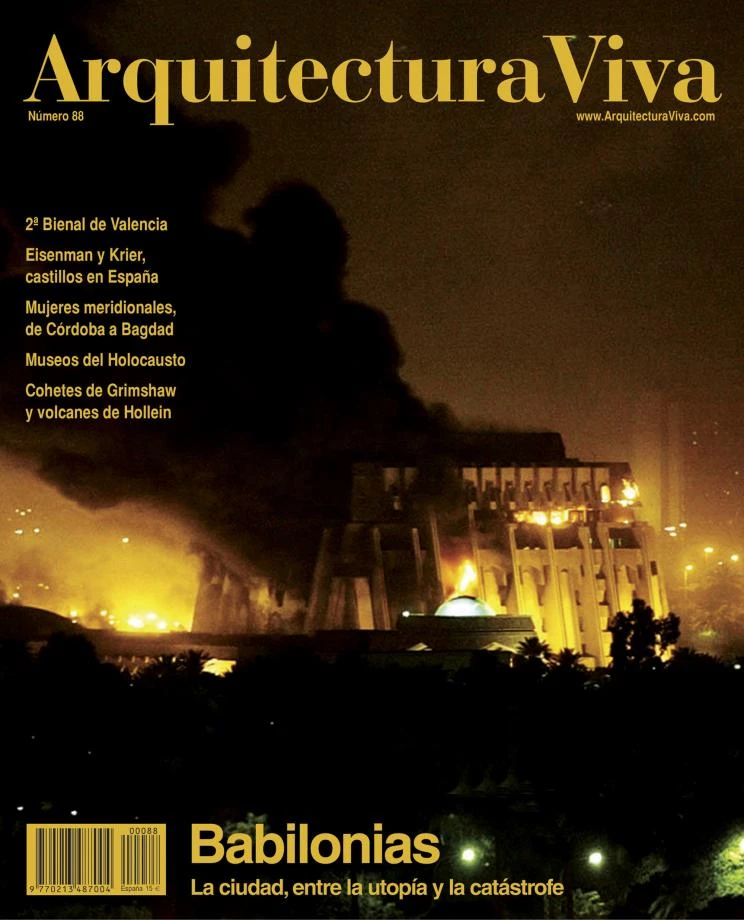

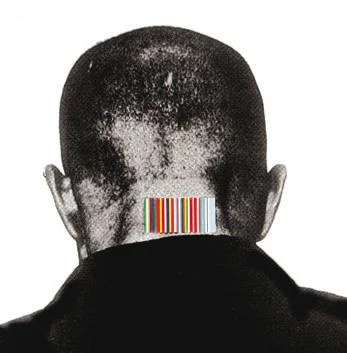

Invited to discuss the future of the European capital, Rem Koolhaas proposed to change some symbols of the EU: a bar-code flag could serve better to represent the utilitarian nature of this political union.

Destined to be the main headquarters of Chinese television, and scheduled for completion before the Beijing Olympics in 2008, Koolhaas’ first sky-scraper consists of a bar that bends several times to form a twisted loop, the underlying idea being to smoothly connect all the departments of the company. But according to the architect, its unique shape also addresses the call to rethink skyscrap-ers in the wake of 9-11, through high-rise buildings “that are not about height and that can define a place rather than simply occupy it.” The 230 me-ters of the new CCTV headquarters will as a matter of fact make it Beijing’s tallest construction (very far, though, from the world records currently being reached in Shanghai and Hong Kong, and sure to be surpassed in the future by several of the 300 tow-ers that will soon go up in the Chinese capital), but this is a rather secondary circumstance. What made Koolhaas prevail over Ito, Perrault, KPF, SOM, and a number of Asian firms was the uniqueness of his formal strategy, with the two leaning towers joined at the base and the top to shape a gigantic window and baldachin that will serve as a logo for the state-controlled TV network, and perhaps also for the Olympic Games and the city of Beijing. Indebted to some recent projects (Steven Holl’s diagrammatic Retaining Bars in Phoenix or Peter Eisenman’s Max Reinhardt Haus in Berlin) but also to works like Philip Johnson’s KIO Towers in Madrid (which Koolhaas judged exemplary when local architects took it for no more than a crude expression of the decline of politics and culture in the early nineties) and to canonical designs of the avant-garde like El Lissitzky’s Wolkenbügel (Cloud-hanger), the loop of the CCTV is decked with an irregular grid drawn by the engineer Cecil Balmond as a materialization of structural efforts, and yet seeming as superficial as the diagonal grids of Libeskind’s facades in his Ground Zero proposal, or the textile patterns of the same Libeskind with Balmond in London’s V&A. In the final analysis, Koolhaas is giving Beijing a spectacular icon that reflects both the communicatory ambition of China’s totalitarian capitalism and its determination to adapt to the symbolic codes of western economies, and it is in the acceptance of this mediatic commerciality where his clairvoyance and his cynicism are to be found.

The European cohesion is based on a community of commercial and economic interests, and this hard fact is illustrated in the study carried out by the Dutch architect with a map drawn as a motley collage of brands.

Identical intellectual features are present in the work Koolhaas undertook for the European Commission. The heterogeneous nature of European institutions and the utilitarian condition of its politi-cal project inspired the architect to represent the continent as a motley collage of trademarks, and propose a new continental flag that resulted from merging national ones in a chromatic bar code, a brilliant synthesis that expresses both Europe’s fragmentation and its provisional cohesion through commercial interests. But this hedonistic and prosperous Europe that is more Kantian than Hobbesian, and more given to consumerism than to the imposition of an identity, fell into its own crisis after 9-11, and broke apart altogether in the UN Security Council debates that preceded the Iraqi war. Along with other Pritzker winners, Rem Koolhaas has been invited to compete for the enlargement of the UN headquarters in New York, a mythical building of his admired Wallace Harrison that postwar idealism wanted as the seat of a world government. But this pillar of the pacific organization of a diverse planet is now seriously damaged, and hopes for its architectural regeneration are as scarce as the prospects of an ironic flag being placidly ac-cepted by a divided and hesitating continent. It is not easy to augur good times for a Europe of Venus when the world comes under the sign of Mars.[+][+][+]