Yes, the show must go on. We have entered the 21st century through a gate of fire (Kofi Annan dixit), and having traversed this threshold of death, we only find more of the same: to avoid falling, we must keep pedaling on the bicycle of spectacle. Tom Wolfe thinks that, in the wake of 11 September, architects will abandon style for content, but such a pious conjecture is more a wish than a prediction: we can still perceive no other aroma than that of melancholic surrender to the inertia of images. In Afghanistan, improvised guides of the Northern Alliance show the training fields of Al Qaeda and the successive homes of Osama bin Laden as tourist spots, and in New York, over thirty museums seek out objects related to the destruction of the World Trade Center – fragments of the buildings, crushed taxis, the suit Giuliani wore – to exhibit in galleries commemorating the event. The disorder of the world troubles the streets, but the show must go on.

The Guggenheim museum branches (a large shed and a small box) are new attractions of The Venetian casino in Las Vegas. The canopy with a facsimile of the Sistine Chapel that protects the shed skylight is a tribute to Venturi.

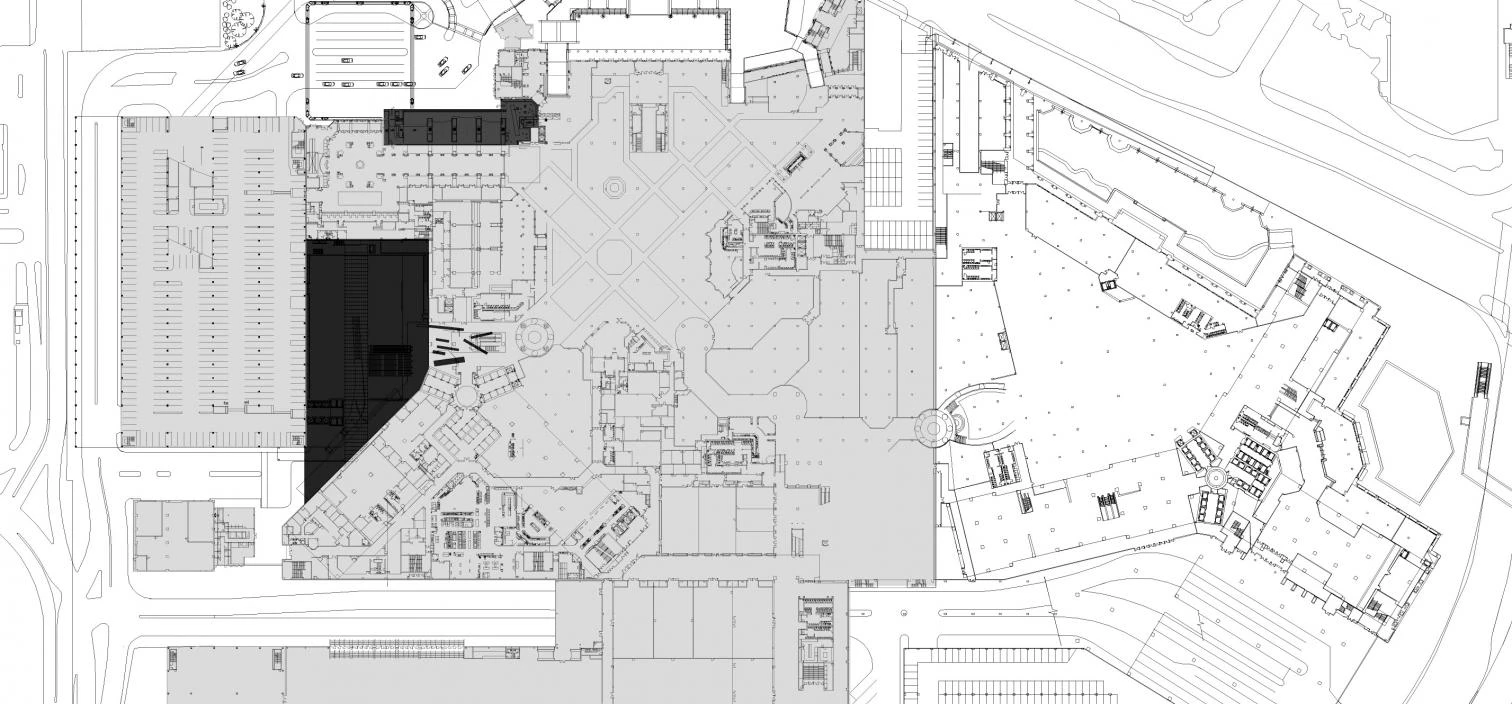

Las Vegas: 33 million visitors a year, Americas fastest growing city. Over a thunderous plinth of slot machines, the hotel-casino called The Venetian boasts a replica of the Piazza San Marco, the Grand Canal complete with gondoliers, and, since October of last year, two museums of high culture. Designed by the Dutch Rem Koolhaas, the Guggenheim Las Vegas and the Guggenheim Hermitage are, at $15 an entrance ticket, fundaising franchises of two museums soon to be joined in the area, thanks to the lure of jingling coins, by Viennas Kunsthistorisches. (Eduardo Serra’s Prado Museum, still splashing in the puddle of the enlargement, has let the train go by, but when it manages to get out of those muddy waters it may still have the option of opening a profitable branch in Benidorm!)

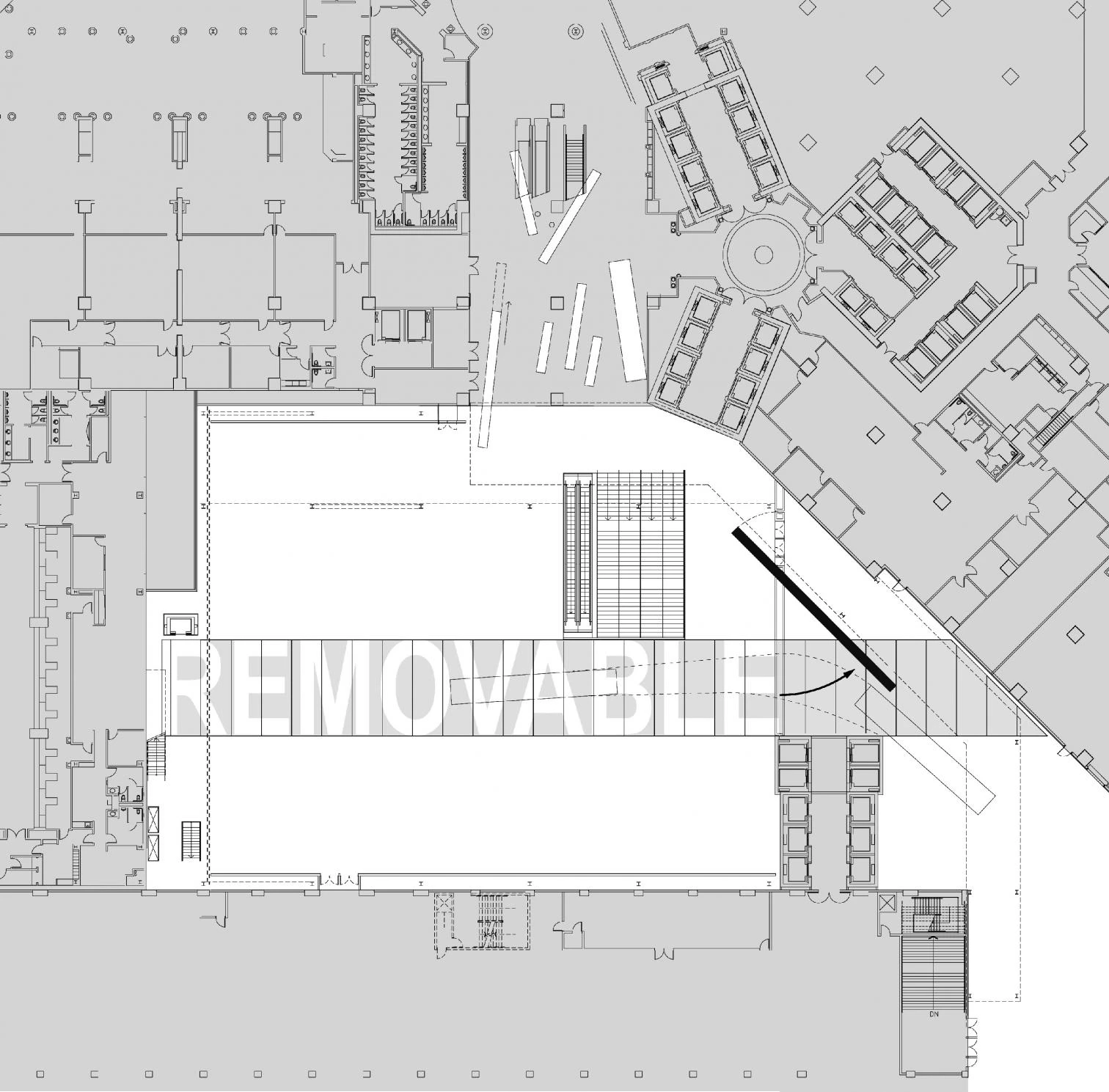

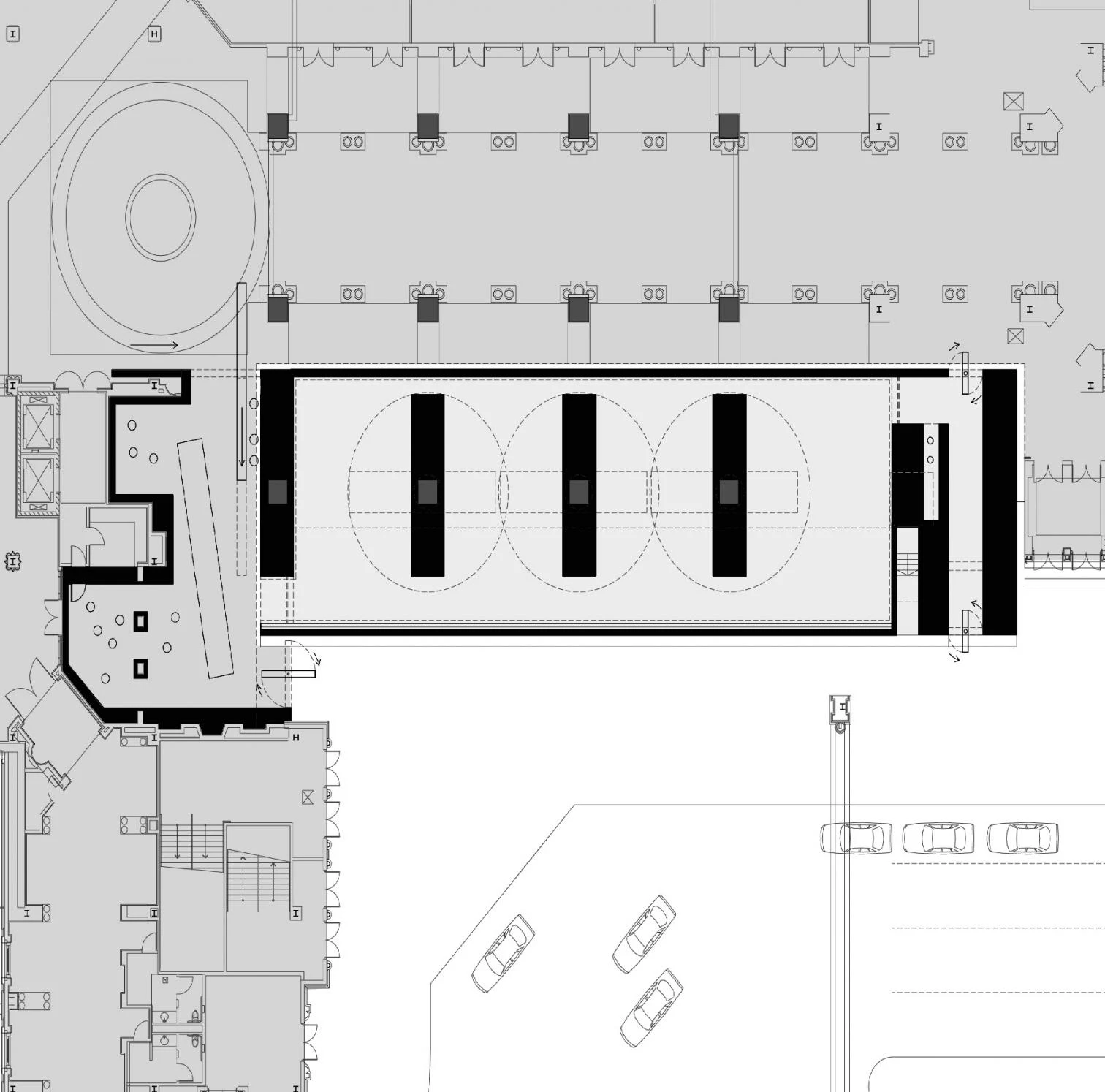

The Guggenheim Las Vegas is a huge, 6,000-square-meter industrial shed with a bridge-crane and an enormous garage pit of sorts that visually connects the two superposed floors. Over them, a large skylight nuances the atmosphere with a mechanized levered canopy, decorated with a facsimile of the Sistine Chapel ceiling that aims to be an ironic reference to Las Vegas kitsch, with Michelangelo presented through the pop, mannerist eye of Robert Venturi. The museum opened with the motorcycle exhibition previously shown in New York and Bilbao, reinstalled by Frank Gehry with undulating sheets of stainless steel and meshes of metal wiring, and reinaugurated by Guggenheim director Thomas Krens with actors Dennis Hopper and Jeremy Irons aboard their vehicles in Easy Rider style: all slightly déjà vu. In contrast to this colossal container, the Guggenheim Hermitage is an austere, 700-square-meter box of Cor-Ten steel (to which the paintings hang on through magnets) attached to a gallery adorned with appalling frescoes that links the hotel lobby to its noisy casino. For a start, 45 works from the museum’s permanent collections are on display here.

The lobby of the casino (right) links Koolhaas’s two constructions. The Guggenheim Las Vegas – an industrial shed fit for travelling blockbusters –was inaugurated with a motorcycle exhibition designed by Frank Gehry.

Designed and built in a year, the two museum branches are sober and effective pieces that owe their notoriety to the clout of the institutions involved, the visibility of the place, and the fame of the architect, all of which share an interest in commerce, publicity, and fashion – ingredients which, to be sure, form part of the profile of Krens’s Guggenheim, the urban personality of Las Vegas and, more and more, the career of Koolhaas. The latter’s obsession with consumerism has led him to put together a voluminous guide about shopping –launched jointly by Harvard University and the publishing house of Taschen, a rare marriage that throws light on the strange times we are living; his interest in publicity has made him set up an office in parallel to the original OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture), which under the label of AMO is dedicated to studies, promotional work and public relations, as well as initiate a collaboration with Condé Nast publishers as a magazine advisor; and his fascination for fashion has driven him to put his very best into a collaboration with Prada, a firm already being announced in Wallpaper with photographs of the Dutch architect’s characteristic models graced by miniature figures.

Trapped in the vertiginous eddy of celebrity, Koolhaas – winner of the 2000 Pritzker Prize –seems to be wasting his considerable gifts on trivial matters, while his public fame turns him into a permanent source of news good and bad. As a latest hitch in his career, he has been tried for plagiarism. An architect who worked in his London office alleged that the Kunsthal in Rotterdam was copied from a project he drew up himself in the course of his last year at the Architectural Assocation, a town hall on the docks of the British capital. After a court battle of eight years, in November a judge of the High Court ruled in favor of Koolhaas, but whereas the claimant, Gareth Pearce, obtained public financial aid for his legal expenditures of 465,000 e, the Dutch architect will be hard-pressed to recover the amount he has spent on lawyers, which lies in the area of 800,000 e. A month later, perhaps as compensation, came the news that Koolhaas had beaten Nouvel, Holl, Libeskind and Morphosis in the race for the enlargement of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, an ambitious project for one of California’s major cultural institutions, and it was also announced that he had been selected to build a theater for the performing arts in Dallas, in this case overVan Berkel, Snøhetta, and again Libeskind. Fame presses, but does not strangle.

With his implacable mix of cynicism and lucidity, Koolhaas can be exasperating. But we must acknowledge that no one else has known how accept and make something out of the consumerist and mediatic superficiality of our world. We pretend to be interested in his vacuous works only because his perverse intelligence astonishes us. Barring obvious and murderous differences, it is the same genre of fascination and repulsion provoked in many of us by Osama bin Laden, a charismatic figure whose lure cannot be abstracted from his ominous audacity... Or can’t we at once admire the beauty of the burkha – more appealing, in Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar, than Issey Miyake’s clothes – and reject it as a symbol of the oppression of the Afghan woman, being a traditional garment that provides privacy and protection at the same time that it sequesters the gaze and the body of women in a portable prison? If the western female is that represented by Catherine M. and The Pianist, can we not for a moment see things from the point of view of the barbarians who contemplate the corruption of the empire camped on its borders?

Much smaller, but as functional and crisp as the other exhibition space, the Guggenheim Hermitage is a Cor-Ten steel box whose walls display paintings from the permanent collections of both museums.

Perhaps, as Álvaro Mutis thinks, we humans have failed as a species. But, as Rem Koolhaas knows, the band of the Titanic must keep playing til the end. Apparently, as a result of the negotiations with the Kunsthistorisches, the next exhibition to be held in The Venetian will bring to Las Vegas the mythical Brueghels of Vienna, including the luminous and cluttered Tower of Babel. But for display in Nevada, the temperature of the times would demand instead the Flemish painter’s other Tower of Babel, the tragic, somber version of the Biblical theme conserved in the Boymans-van Beuningen Museum of Rotterdam, not in vain Rem’s home city. Quosque tandem, Koolhaas?