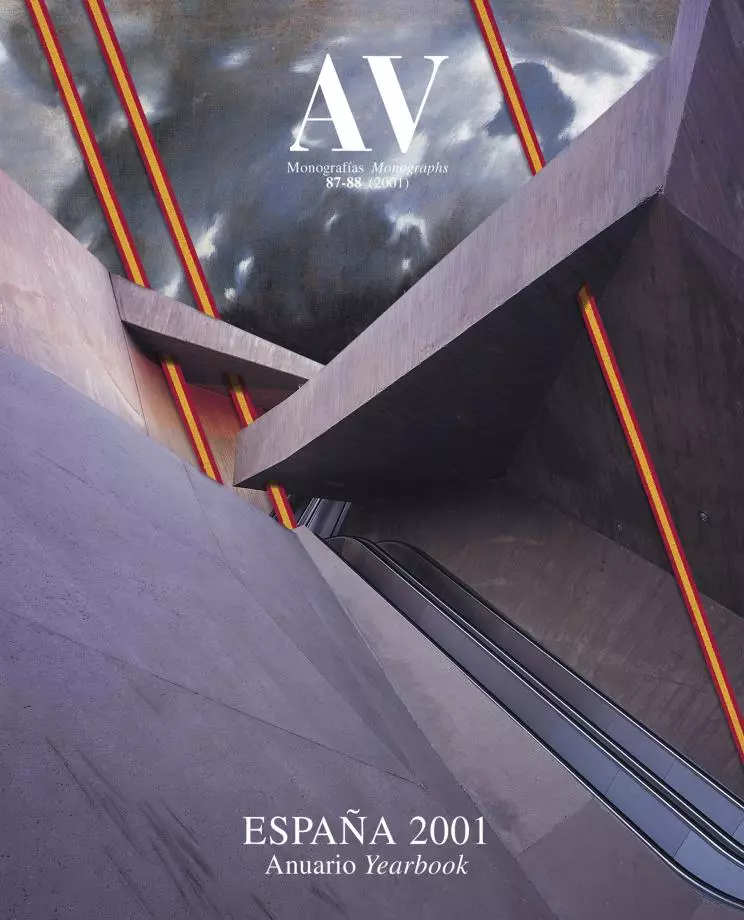

American Beauty

Dream and Nightmare in the Sprawling City

American beauty is a rose variety that is scentless and thornless. In the movie of the British director Sam Mendes, American Beauty refers to the spruce roses that Annette Bening cultivates, to the teenaged cheerleader played by Mena Suvari, but especially to the sweet, empty perfection of the residential developments that materialize the smug prosperity of the American dream; a way of life that comes in conflict with Kevin Spacey’s Lester Burnham, tragic and comic victim of the questionable suburban beauty. “This is my neighborhood, this is my street, this is my life”: over an aerial view of the houses and gardens that characterize the dispersed American city, Lester announces his forthcoming death, sacrificed as he is to the lethal beauty of a hollow existence, and this fable of suburban life becomes an apologue about the alienation of the ‘house on a lot’. To the extent that this urban model begins to be ours as well, the malaise brought on by the odorless beauty of the spikeless rose also becomes a warning parable for Europeans living in the new peripheries.

That sweet and empty perfect life proffered by the residential developments where the American dream of prosperity materializes is reflected with moving precision in the film American Beauty.

The five Oscars reaped by Steven Spielberg’s production company Dreamworks not only acknowledge the reiterated leftist critique on the trivial tedium of the suburban dreamland, from dirty minimalism to The Simpsons.They also come in tune with the current American debate on sprawl, the uncontrolled urban growth that destroys the environment with its voracious consumption of land and the energy waste and pollution brought on by the ensuing increased traffic. The Vice President Al Gore has launched a legislative crusade against sprawl as part of his presidential campaign, but many of his Republican opponents coincide with him in opposing this unwise growth based on gasoline and asphalt which few, after all, hesitate to describe as inefficient and ugly. The conservation of free spaces, the protection of landscape and the control of indiscriminate urbanization are today essential themes of political debate on quality of life.

For New York critics – writing, as they do, from a city undergoing a formidable renaissance – the suburban world of gardens, garages and malls is a false Arcadia that, by avoiding spontaneous social contact, traps the dream of the middle classes in an autistic bubble. Herbert Muschamp in The New York Times judges dispersed urbanization as the camouflage of the consumerist society that was established from 1945 on, whose principal propagandists were the designers Charles and Ray Eames, and sees in the exodus to the suburbs a mechanism of alienation that induces people to find satisfaction in the compulsive acquisition of useless goods. And Paul Goldberger in The New Yorker considers the two most important urbanistic actions in the history of the United States to have been the granting of mortgage guarantees to World War II veterans (which subsidized the purchase of suburban houses) and the interstate highway law (which with federal funding financed the diffusion of the private vehicle at the expense of mass transport), stressing the “fundamental contradiction” between a civilized community and the automobile.

In America’s current debate on sprawl, or the uncontrolled urban growth, the detractors of the new housing developments warn about its devastating effect on the landscape and the free spaces.

The only objection to this choral lambasting of the lawn is offered by the British weekly The Economist, which after a series of six articles on American sprawl still manages to find splendor in the grass, arguing that Hollywood’s tycoons and his compatriot Sam Mendes criticize the ‘American beauty’ of the dispersed city out of clichés and ignorance. “Life is more interesting than art,” says the lone dissenting voice, because nearly everything innovative about the American economy – from California’s Silicon Valley to Seattle’s Microsoft headquarters – is forged in the suburbs. “The new ecocomy and the new suburbs are really the same thing,” it continues, quoting a professor of New York’s Cooper Union. The article suggests that sprawl is not the menacing monster many think it is, but “a hammering that spreads the country in thin sheets, like gold leaf,” and advises Gore not to antagonize his suburban voters. The British Prime Minister Tony Blair recently received similar counsel, and quickly filed the report of the commission led by his friend the architect Richard Rogers, who had recommended prohibiting building in intact areas to stimulate the development of ‘brown areas’ (zones previously built on) and thereby arrest asphalt’s invasion of the countryside.

But somewhere between the Escila of the congested metropolis and the Caribdis of residential atomization, and in the United States itself, alternatives have emerged which endeavor to reconcile civil demands for community living with that antiurban Utopia that has its roots in Jefferson’s agrarian traditionalism. The democratic candidate for New York senator, Hillary Clinton, wrote a book, It Takes a Village, which advocates the recuperation of community ties against extreme neoliberal individualism, and its metaphor of a village is in tune with the growing popularity of small towns that try to blend city and nature in the placid crucible of nostalgia, as well as with the intellectual revival of Norman Rockwell’s neighborly images that has led to the current monographic exhibit of the painter and illustrator which is culminating its long American tour in the sanctuary of New York’s Guggenheim. In any case the Mecca of this populist renaissance continues to be Florida, where the ‘new urbanists’ have built a series of neotraditional developments – from Seaside, setting of The Truman Show, to Celebration, a Disney project outside Orlando – that preserve scent without the protection of thorns. An impossible rose, perhaps, but one whose gardeners deserve applause.

Florida, Politics and New Urbanism

The leaders of the movement called New Urbanism (malevolently New Suburbanism to some), are the Cuban-born architect Andrés Duany and his wife, architect and professor Elizabeth Plater-Zyberg, who from their Miami studio have in the past twenty years designed numerous developments endowed with sidewalks, parks and squares – elements which, while not altogether forgetting that the citizen is a consumer, endeavor to repair the cracks of America’s residential Arcadia through a retrieved density that would render the car unnecessary for many everyday activities. Against the elementary particle of the dispersed city, the one-family house they call McMansion in their book Suburban Nation, the Florida couple prescribes compactness and public space: urban medicines to cure the disease of sprawl and the decline of the American dream. Like the Californian Eameses of Cold War years, though with an architectural traditionalism that the majority of their colleagues abhor, the DPZ team promotes the domestic Utopia as a showcase of American life, a powerful magnet that before sent people jumping over the Berlin Wall and now pulls hundreds on rafts to the keys of Florida. In 1959 the Eameses participated in the U.S. pavilion of the Moscow World’s Fair, in the model kitchen of which Nixon and Khrushchev had their famous exchange about the domestic advantages of their respective systems. Forty years later the boy Elián would smile at cameras from the Miami garden of his granduncle and grandaunt, with no idea of the political tug of war being waged for his custody. In 1858 Pius IX had sequestered another six-year-old boy, the Jewish Edgardo Mortara, baptized in secret by a servant, and the scandal took on such colossal dimensions that the Pope of the Syllabus lost prestige not only in the eyes of members of other religions but also among his own Catholic faithful, debilitating the Church in front of the nationalist Risorgimento. In time little Edgardo – about whom stories of miraculous transformations were quick to circulate – would be ordained a priest. Today, as we watch Gore cynically supporting little Elián’s retention on U.S. soil in his race for Florida votes, it seems to me that the holy boy saved by dolphins is destined to become a urbanist. A New Urbanist, of course.