History will absolve RobertVenturi.The great American architect and theorist preached, back in the sixties and seventies, a pop architecture that was more attentive to the ordinary than to the heroic, more sensitive to common tastes than to the refinement of elites; but his theses were later discredited, towed as they were by the uncertain quality of Venturi’s actual buildings, as well as by the tide of trivial constructions that characterized the eighties, thanks to postmodern architects claiming to be disciples of his. Today, however, the same architects that brought on the ‘deconstructivist’break with Venturi’s populism are making expiatory pilgrimages to the sacred places of his esthetic religion: to the Disney sites at the beginning, and not because the company of the mouse had in the past hired architects known for their shaken forms to build its new amusement parks, but deliberately pursuing the conventional popularity of the Disney house style; and now, finally, carried by the muscular and vulgar wave of America’s economic euphoria, to the ultimate destination of crass commercial excitement, Las Vegas.

Venturi’s populism returns to architectural debate through Koolhaas, who has designed two galleries in the casino The Venetian of Las Vegas to house exhibitions of the Guggenheim and Hermitage museums.

Venturi took his Yale students there in 1968, and the result of that class trip was a mythical book, Learning from Las Vegas, which appeared with the explanatory subtitle ‘The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form’, surely less expressive than that coined by the students, ‘The Great Proletarian Cultural Engine’. This very engine of leisure, which welcomes over 36 million visitors annually, will in the next year be presenting, within the complex of the casino The Venetian, the fruit of the first collaboration between the Guggenheim Museum of New York and the Hermitage of St. Petersburg: an art gallery designed by the Dutch Rem Koolhaas to display works from both institutions, and to be complemented by a colossal exhibition hall – also drawn up by OMA, Koolhaas’ Rotterdam studio – for the Guggenheim to bring its blockbuster shows to, such as the already hugely popular one on motorcycles which with a montage by the Californian Frank Gehry will serve as opening exhibit.

Koolhaas, who recently saw his Los Angeles project for Universal Studios canceled, here has the opportunity to materialize his lucid and cynical the-ses on the ‘junkspace’ of the leisure industry. In his latest writing under that title, the newest Pritzker winner encourages us to “...discover Casinos, investigate Theme Parks. Our concern for the people has made people’s architecture invisible... In Junkspace, old aura encounters new luster to spawn sudden commercial viability... Barcelona amalgamated with the Olympics, Bilbao with Guggenheim, 42nd with Disney.” In Las Vegas, Koolhaas will be the priest officiating the marriage of the Guggenheim to the Hermitage, and of both to the newest casino on the Strip, a reproduction of the city of Venice complete with canals, gondolas and a life-size Rialto bridge.

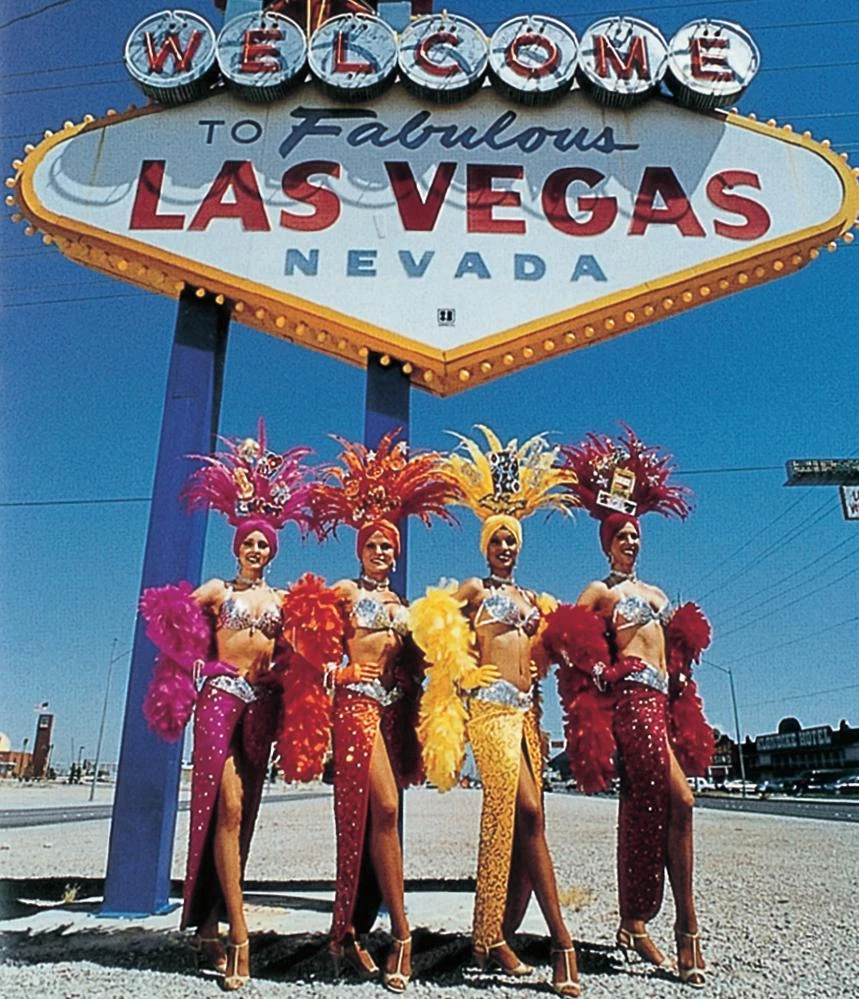

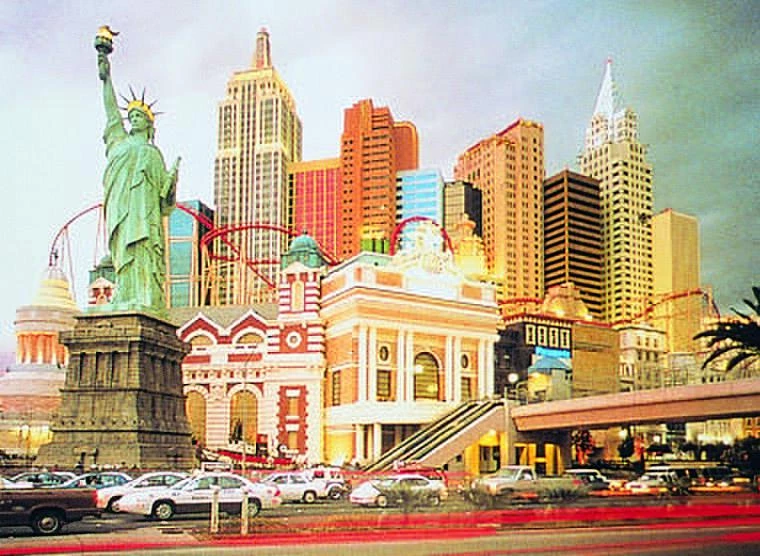

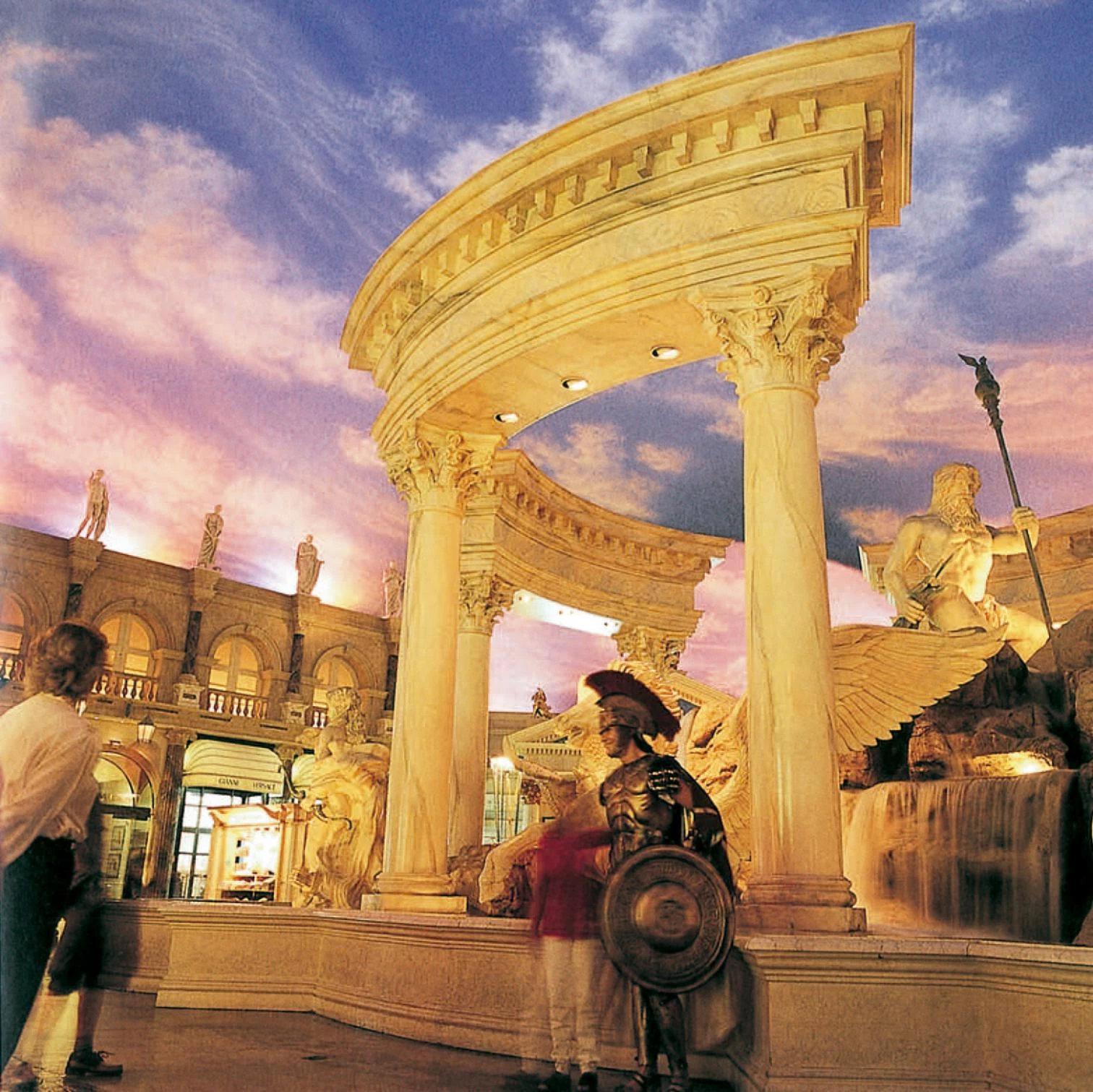

When Las Vegas lost monopoly over gambling it was forced to forge a new identity, and all bets were on the theme hotels. From the festive imitation of classical Rome set up at Caesars Palace to the replica of the Italian canal city in The Venetian, all the way to the skyscrapers and monuments of the Big Apple in New York New York, the former ‘city of sin’ has successfully completed its Disneyfication.

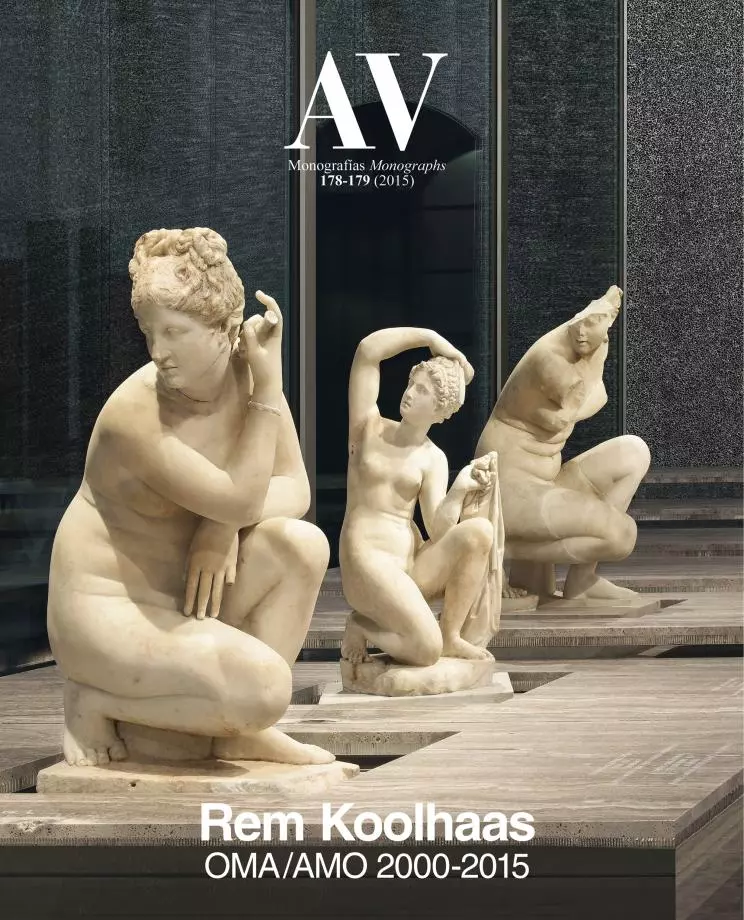

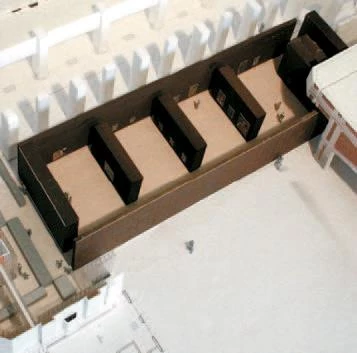

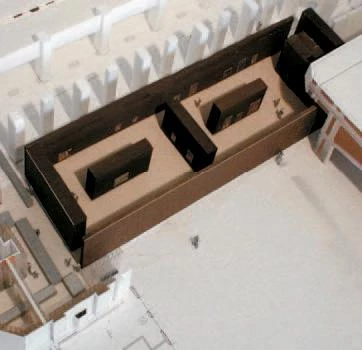

Into the busy foyer of The Venetian, which is traversed by 100,000 visitors daily, will go the art room known as The Jewelbox, a 700 square meter gallery that has already been given the emphatic name of Hermitage-Guggenheim Museum, designed by Koolhaas with coreten steel walls and which is to be inaugurated in the spring of 2001 with forty impressionist and modern avant-garde works from the permanent collections of the two institutions. And construction work has already begun for the separate building within the casino complex that is to be the 6,000 square meter exhibition hall denominated Guggenheim Las Vegas, conceived by the same architect as a huge skylit hangar 20 meters tall, with a crane-bridge reinforcing its industrial look, and which is due to open later in the summer with the motorcycles previously displayed in the venues of New York and Bilbao.

The recent, much debated enthusiasm of Koolhaas for Las Vegas was not initially shared by Thomas Krens, director of the Guggenheim Foundation, to whom The Venetian’s owners had originally addressed the proposal to bring the ‘Art and the Motorcycle’to the casino; but memories of Venturi’s eulogies and the readiness of the hoteliers to build new spaces designed by the Rotterdam architect assuaged his reservations about what he had first deemed “too tacky”. However, at the beginning Bilbao also seemed to him a highly unlikely place, “but the more unlikely the place, the more interesting the opportunities. ”And as for the Russians, their extreme economic depression makes it difficult nowadays for them to reject any proposal that seems financially desirable, a circumstance they in this case cover up with the naive explanations offered by the Hermitage’s director, Mikhail Piotrovsky, to The New York Times: “Las Vegas is America; it is a place where a lot of people go. And in Russia we are accustomed to bringing art and culture where the people are. It is part of a normal tradition, a kind of Soviet tradition to educate the masses.” So maybe Venturi’s students understood Las Vegas better than he did, and maybe the enormous casinos that are going up like a theme mirage on the Nevada desert are, in the final analysis, simply an expression of “the great proletarian cultural engine.”

Fair Play in an Oasis of Leisure

Las Vegas lost monopoly over gambling in 1971, when Atlantic City legalized its casinos and the old ‘city of sin’was forced to forge for itself a new identity. It decided to bet on theme hotels – establishments no longer catering exclusively to gamblers, but also to a new clientele brought in by organized tours, holidays and conventions. Thirty years later, the Disneyfication of Las Vegas has made it the fastest growing North American city, and the old gangsters who controlled gambling have given way to hotel magnates providing family entertainment. The pioneer of this shift was an Atlanta developer named Jay Sarno, when in 1966 he opened Caesars Palace, a gigantic hotel and casino designed as a festive imitation of classical Rome; and the most recent incorporation into this theme fever are the clients of Koolhaas, Sheldon Adelson and Rob Goldstein, with the inauguration in the summer of 1999 of The Venetian, the casino fashioned after the Italian canal city which is also a convention center and a shopping mall with stores and restaurants, besides a hotel with 3,000 rooms which a planned enlargement to provide another 3,000 will turn into the world’s largest. But the most successful developer in Las Vegas is perhaps Steve Wynn, whose Mirage of 1989 sparked the wave of spectacle buildings of the nineties: the Arthurian Excalibur, the inevitably pyramidal Luxor, the clustered skyscrapers of New York New York, all the way to his own Bellagio of 1998, the poshest of all, whose Gallery of Fine Art is the immediate precedent of the matrimonial adventure that the Guggenheim and the Hermitage are undertaking in this oasis of Nevada.