North facade with the new staircase by Pedro Muguruza

The collection of the Prado Museum took three centuries to assemble, and the building that houses it has been under construction for two. If the museum’s artistic history is the history of the royal collections – of the Habsburgs in the 16th and 17th centuries and of the Bourbons in the 18th – its institutional history is tangled up with the history of its building, designed by Juan de Villanueva in 1785 and transformed or expanded by many other architects in the course of the next two centuries.

The Collector Monarchs

Although the royal courts of the 15th century were always on the move, making it necessary to transport the furniture, carpets, tapestries, and artworks that made the empty fortresses and inhospitable manors they stopped at inhabitable, and although this nomadic life perhaps instilled the collector’s spirit in the monarchs – Queen Isabella left over 400 panel paintings when she died –, it was in the following century that the relationship between the Spanish crown and the arts began to forge. Charles of Ghent, grandson of Maximilian I and the Catholic Monarchs, was raised in the court of Mechelen by his aunt Margaret, governor of the Netherlands and patron of the arts, and in this early training, as Jonathan Brown has pointed out, lay the seed that bore fruit when he, as Emperor Charles V, met Titian in Mantua in 1532, striking up with him a long, fertile relationship. Philip II – in whose education his mother, Isabella of Portugal, was actively involved, and who even as a prince met with Titian in Milan in 1548 – inherited the Titians of his father and his aunt Mary of Hungary, and became the painter’s leading client and the period’s greatest patron, acquiring numerous Venetian and Flemish pieces, especially by Hieronymous Bosch. This formidable collection would experience a definitive push with his grandson, Philip IV, refined connoisseur of the arts, the greatest collector of paintings of the 17th century, to whom the current museum owes the presence in its galleries of Velázquez and Rubens.

The Bourbons were hard put to match this legacy of excellence, and under Philip V there was the catastrophic fire at the Alcázar in 1734, which burned 500 paintings, but the collector’s zeal of Elizabeth Farnese, his second wife, who revived admiration for Murillo; the acquisitions of Charles III and his support of Tiepolo or Mengs; and above all the protection of Goya by Charles IV – who knew more about painting than about government – together enriched the collections with essential works and painters. When Ferdinand VII opened the collection to the public in 1819, inaugurating the Prado Museum, it was the culmination of a great cycle of acquisitions (the most important one of the next phase would be the incorporation, in 1872, of the paintings of the Trinidad Museum, created in 1837 with artworks confiscated from convents and monasteries), the fundamental episodes of the Prado’s artistic history were completed, and thus began an institutional history that is tangled up with the history of the building that is home to it, stretching from Charles III’s commissioning of a Natural History Museum to the recent competition to renovate the Hall of Realms and make it part of the Prado campus.

Villanueva’s Project

As is well known, the building by Villanueva was not originally conceived as an art museum, but as a Natural History Museum and Science Academy. Along the Paseo del Prado the enlightened Charles III had promoted the creation of scientific institutions like the Botanical Gardens and the Astronomical Observatory, in both of which Villanueva took part as an architect, and it was precisely the director of the former, José Pérez Caballero, who proposed to Minister Floridablanca that a Natural History Museum and a Chemical Laboratory be built on land adjacent to the Gardens. Count Floridablanca supported the initiative and added to the program a Science Academy, another institution then being debated on in court circles, so with the king’s approval the endeavor was entrusted to Villanueva in 1785, shelving the project for the Chemical Laboratory that had been drawn up the previous year, for the same site, by a disciple of Francisco Sabatini, Antonio Bereto, that Villanueva had censured, as “ordinary in form and construction,” a severe judgment that the architect would recall in his Description of 1796: “My sincerity could not contain my disdain and disapproval.”

The diversity of uses and the way the Paseo del Prado slopes down southward made Villanueva propose a building which, as Fernando Chueca once well described, is composed of autonomous parts – the rotundas at the ends, the temple of the central volume, and the palatial gallery that connects them – and both its two main levels are ‘ground floors’ because the lower one is entered from the south end facing the Botanical Gardens, and the upper one from the north end at the foot of the Jerónimos church and cloister. These two entrances – the one of the Botany and Chemistry schools on the south, organized with a Corinthian order, and the one of the gallery-museum on the north, framed by Ionic columns like those also used in the grand rotunda immediately inside – are complemented by the central access to the Grand Hall of the Science Academy through the huge Doric portico that opens out to the Paseo del Prado. Parallel to this and also flanked by columns flows, in Villanueva’s words, the “spacious and prolonged gallery” that was intended as a museum of Natural History, and is now one of paintings. Such unique arrangement of autonomous pieces and independent floors explains the absence of a grand central staircase; a circumstance that has made circulation difficult in the building when used only as a museum, but which challenged the architect when asked to solve the unusual assemblage of functions.

From Natural History to Fine Arts

As was his practice, Villanueva submitted two proposals to Floridablanca, who in turn presented to the king, for royal approval, the less costly one, which did without the covered porticos for the public promenade that stretched along the main facade; a possible explanation for the edifice’s being so set back from the Paseo del Prado alignment, marked by the fences of the Botanical Gardens. Execution of this project, which Villanueva described as ‘more moderate,’ began that same year, and progressed at a good pace while Floridablanca held office, but Charles III died in 1788 and in 1792 the minister was replaced by his rival, the Count of Aranda. Construction work slowed down and was still unfinished in 1808, when its use as a barracks for the French cavalry caused extreme deterioration, further accentuated by the looting of lead and slate from the roofs. After the pillage of the French occupation, and Villanueva’s death in 1811, the task of completing the building was entrusted in 1814 to his disciple Antonio López Aguado, who repaired the vaults and roofs as economically as possible, and the building finally opened as the Fine Arts Gallery on 19 November 1819, a year after the demise of its main patron, Ferdinand VII’s second wife, Isabel de Braganza, whose love of the arts was instrumental in facilitating both the cession of paintings and the charging of the museum’s construction and maintenance to the king’s ‘secret pocket.’

The extraordinary work of Villanueva, leading exponent of neoclassicism in Spain, and for many also an early romantic in the picturesque nature of his foreshortened views – repeatedly chosen by the painters and engravers who depicted it, often from the north end, with the curved access ramp and the slopes separating it from the Jerónimos monastery, and who so efficiently captured the architect’s topographical intelligence –, was thereafter used for storing and displaying the royal collections of painting and sculpture: the canvases upstairs, in the great gallery now illuminated by skylights in the plaster vaults that had replaced those decomposed by moisture; and the sculptures downstairs, with an entrance facing the Botanical Gardens but, at least until 1826, still sharing space with objects of Natural Science.

The Exhibition of the Paintings

It must be mentioned that the museum opened with paintings of the Spanish school exclusively: 311 canvases (out of 1,531 in storage) on display – in the cluttered way that was usual in those days – in the three rooms adjacent to the rotunda of the main floor. In tune with the rise of national pride – and also, as Francisco Calvo Serraller has explained, with initiatives of the Bonapartes in Amsterdam, Kassel, or Milan that expressed the Empire’s policies in the realm of the arts –, the exhibition of Spanish masters had a propaganda component that was already present in the decree that created the never-born ‘Museo Josefino,’ which Joseph Bonaparte modeled after the Musée Napoleon, and which in 1809 was purported to “highlight the merit of the acclaimed Spanish painters, little known in neighboring nations.” But the Italian school was by far the most prestigious, and – as José Manuel Matilla and Javier Portús have documented in detail – only Italian canvases were on view in the central gallery for almost a half-century: in 1821 there were 195 Italian paintings in the gallery’s north section, and in 1828, 337 Italian works took up the entire gallery. That period saw the addition of paintings from the French and German schools in the central hall of the south end, and also the nudes that were grouped in the Reserved Hall created in the lower level of the south wing. These remained there until 1838, when they were transferred to the ‘rest room’ for monarchs and courtiers, which took up the grand hall of the upper floor, with balconies facing the Botanical Gardens. But only with the 1864 reorganization by Federico de Madrazo – which would in essence be maintained up to the end of the 19th century – did the Spanish and Italian schools come to share the grand gallery, as vehemently desired by so many, including Vicente López as early as 1826.

The different arrangements of paintings were done in parallel with the changes carried out on the building, and after the death of López Aguado in 1831, consolidation of the museum continued under the direction of his architect son, Martín López Aguado, in a line of faithfulness to Villanueva’s design that only began to see significant modifications with Narciso Pascual y Colomer, royal architect and person responsible for the building’s renovations from 1844 to 1854. The most important ones were: the completion of the basilica-like central section, still roofless in 1835, which the author of the Congress of Deputies would execute in 1847-1852 with a gallery held up by metal columns that allow a visual connection between the lower floor of sculptures and the pictorial masterworks that this privileged space is meant for, which would be called the Reina Isabel Hall – in honor of Isabella II, who had come to the throne at the age of 3 in 1833, when Fernando VII died, an event that threatened the survival of the museum, as the paintings were included among the unrestricted testamentary assets, but Isabella’s being a minor postponed execution of the will and the predictable dispersion of the canvases, which would end up attached to crown and nation in 1865 –, a renovation much criticized because of its toll on the contemplation of canvases from an optimal distance, although its selection of paintings would set the bases for an artistic canon of excellence, however changing and in continuous discussion; and the enlargement of the overhead openings of the great gallery, in response to frequent comments of visitors – some coming down to us through chronicles of foreign travelers – on the scant illumination provided by the skylights of the gallery and the balconies at the ends.

Exterior Transformations

At that time, the museum’s surroundings still showed marks of the French occupation, making it necessary to demolish the hurriedly built Buen Retiro Palace, with the exception of the Ballroom and the Hall of Realms, and despite several proposals for gardens to connect the Prado Museum to Retiro Park, in 1865 economic difficulties made Isabella II sell the adjacent lands to the State, which in turn sold them to private hands. Initially urbanized by the architect and engineer Carlos María de Castro – author of the plan for Madrid’s gridded extension, approved in 1860 –, the lands corresponding to the monastery orchards and Buen Retiro Palace would give rise to what is now the Jerónimos neighborhood, substantially altering the area around Villanueva’s building.

Inspired by this, the director Madrazo and the architects of Spain’s public works ministry – as the museum was emancipated from royal tutelage after the Glorious Revolution and the queen’s exile in 1868 – promoted the old idea of making the building a freestanding construction, eliminating the ramp that led to the entrance on the north facade and removing the high ‘trench’ of the east facade, “which besides belittling that architectural work of renown, deprived it of light and salubrity.” The director had urged that the building’s north end be given “some less vulgar and more artistic elevation” and this task fell upon the architect Francisco Jareño, who from 1879 to 1882 designed and executed a staircase that spans the 6.7 meters separating the Ionic portico from the new access level, completely distorting the original idea of Villanueva, who never had an isolated edifice in mind, but a building whose morphology reaps exceptional benefit from the Paseo del Prado’s descent to the Botanical Gardens, in such a way that its two main floors are entered from ground level at both ends.

It was also Jareño’s responsibility to raze Pascual y Colomer’s balcony in the central hall and replace it with a slab of metal structure that would create two independent levels, and transform the oval perimeter of the upper one into a polygon, which is better for hanging pictures. Carried out between 1885 and 1892, the apselike grand hall, reserved for masterworks – at that time designated as the Reina Isabel de Braganza Hall, in remembrance of the museum’s initial supporter and also avoiding mention of Isabella II, who had inspired the first name –, would eventually, in 1899, be dedicated entirely to Velázquez, marking the third centenary of the painter’s birth. As regards his masterpiece, Las Meninas, its symbolic importance would all the more be emphasized when the architect Fernando Arbós – who in 1892 replaced Jareño at the helm of the museum works – gave it a room of its own, adjoining the central hall, built in 1902 and maintained until 1915.

20th-Century Extensions

The 20th century would be the Prado Museum’s age of enlargements, starting with the project designed by Arbós, in 1911-1913, in the form of a bay separated by courtyards of the east facade, completed in 1923, and which set the norm for subsequent expansions: that of Fernando Chueca and Manuel Lorente in 1953, which doubled Arbos’s bay, and that of José María Muguruza in 1964, which, occupying the two courtyards created in the initial extension, disfigured Villanueva’s work completely. But without a doubt, the most important architect of this period was José María Muguruza’s brother Pedro Muguruza, in charge of the building from 1923 to 1951, who replaced Jareño’s staircase with one that allowed access to both floors, tore down the plaster vaults in favor of concrete ones, built a large central stairway, unified pavements, skirtings, and door frames with dark marble, and altered the continuity of the grand gallery with two triumphal arches over pairs of columns (inspired by the Grand Gallery of the Louvre, of the same width but a length of 275 meters, against 105 in the Prado), in such a way that the building we visit today is as much by Villanueva as it is by Muguruza. Pedro Moleón, who has written the best biography of the building, makes a good summary of this sequence of architects: “Villanueva would create, Aguado consolidate, Pascual y Colomer renovate, Jareño isolate, Arbós extend, and Pedro Muguruza replace.”

Muguruza, who was responsible for the museum before and after the Spanish Civil War – during which, in November 1936, it suffered the impact of nine incendiary bombs, prompting the evacuation of the most prized pieces of the collection to Geneva, and Pablo Picasso’s appointment as director, in a propaganda gesture accompanying the commissioning of the Guernica for display in the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris –, also took care of repatriating the canvases and reopening the museum in 1939, and shortly afterwards he replaced the wooden flooring with marble, which reduced the risk of fire that had so dramatically been present during the war.

The final decades of the century – besides various partial interventions carried out by the architects Jaime Lafuente, José María García de Paredes, Francisco Rodríguez Partearroyo, and Dionisio Hernández Gil with Rafael Olalquiaga – saw the museum expand to the neighboring buildings, and so it is that the Natural History Museum that Villanueva designed, weighed down by successive extensions that have attached themselves to the rear facade like rucksacks, has become a campus. Since the failure to use the Villahermosa Palace to exhibit Goya and the 18th century – the building was assigned to the Prado Museum in 1985 and used only for temporary exhibitions until 1990, but was eventually made the home of the Thyssen-Bornesmisza Museum, the collections of which were leased in 1988, and finally acquired in 1993, by the Spanish State – the Prado campus has incoporated several buildings: the Casón del Buen Retiro in 1971, the Herrerian cloister of the Jerónimos convent in the major expansion carried out by Rafael Moneo after the 1998 competition, and, later in the 21st century, the Hall of Realms, which housed the Army Museum until its move to the Alcázar of Toledo in 2010. The Casón, built in the 17th century as the Ballroom of the Buen Retiro Palace and enlarged in the 19th with neoclassical facades to give it a more updated appearance, was for a time home to the Prado’s collection of 19th-century paintings, harbored Picasso’s Guernica until its move to the Reina Sofia Museum in 1992, and since 2009 has housed the museum’s Study Center, as part of the spatial reorganization made possible by the important extension that culminated in 2007.

Moneo’s Prado

This extension followed a controversial international competition called by Spain’s Culture Ministry in 1995, which drew almost 500 entries but was declared void after the announcement of two second prizes and eight mentions that would eventually be part of the subsequent competition. Blunders and imprecisions of the program approved by the museum board, the incompetence and lack of direction of the International Union of Architects, organizer of the process, and the Culture Ministry’s abandonment of its responsibilities brought on a monumental fiasco that moved me to write: “Spain’s major cultural institution deserved more than this, and so did the thousands of architects who squandered time and energy. The competition could have served as an opportunity to think out anew a grand museum and the city’s symbolic heart; it has instead only served to expose the exasperating insufficiencies of the country’s cultural and professional institutions.” The great disappointment of this opera buffa culminated in a new competition among the ten architects selected, but this time with guidelines that prefigured the final result entirely, and Rafael Moneo was declared the winner.

His proposal, which under Calle Ruiz de Alarcón connects the Villanueva building to the Jerónimos cloister – dismantled and then reconstructed inside a brick prism with monumental doors by sculptor Cristina Iglesias –, puts the new entrance and a good part of the auxiliary services in a wedge between the two geometries, conceived with a glass roof and finally executed with a terrace planted with box hedges intended to be a reference to the Botanical Gardens nearby. With the spaces for temporary exhibitions placed in the prism that uses the cloister as a light court, and also in its underground extension, the new structure of circulations and accesses required retransforming the central section of Villanueva’s work, previously modified by Pascual y Colomer, Jareño, and most recently by García de Paredes, transferring the auditorium, built by the latter on the ground floor of the apse, to the subterranean extension, and liberating this area as a foyer. The intervention added 18,000 square meters to the 24,000 of the historical museum, including all previous expansions, so its quantitative importance is clear.

Coda in the Hall of Realms

What is now the museum’s latest enlargement – incorporating the Hall of Realms, which, like the Casón, was part of the Buen Retiro Palace, and which was also much modified in the 19th century – is necessarily smaller because the historical building is only 8,000 square meters in built area, but is unique in acting upon a premise whose pictorial decoration we know in detail, with most of its canvases having survived the vicissitudes of history and come down to our days in the museum’s collections: large depictions of battles, equestrian portraits of kings, and works of Hercules took up the grand representative space of the Spanish monarchy, and this fact has conditioned the designs of the eight teams that have competed to refurbish what was once the Army Museum.

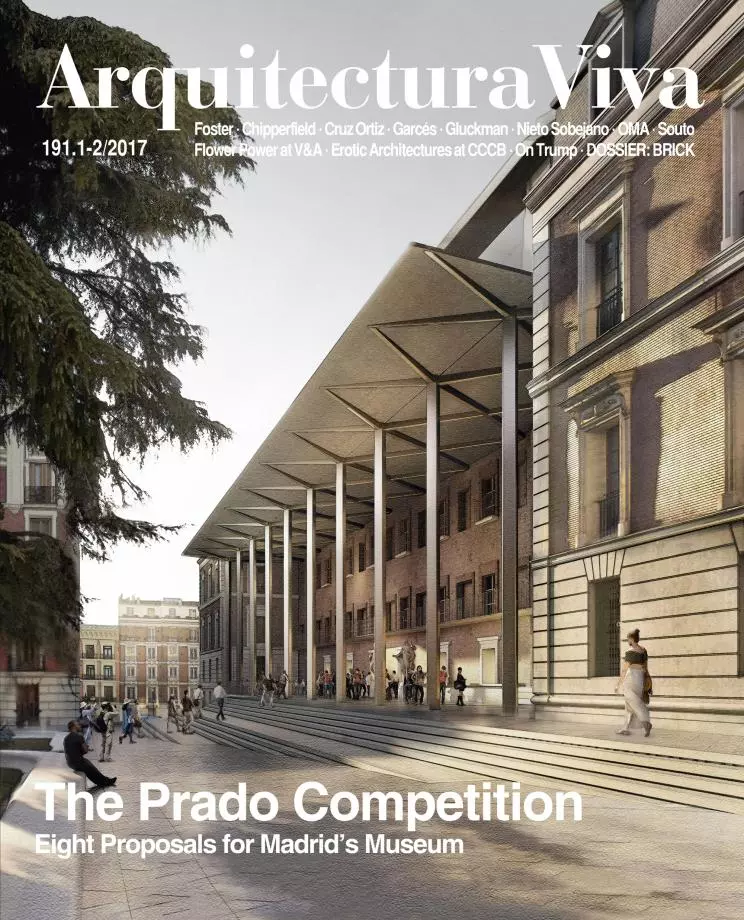

The jury – which included the author of the previous expansion, Rafael Moneo, and also the author of this article – made its decision in November 2016, and the winner, was the design of Norman Foster and Carlos Rubio. Their project recovers the original grade of the ground floor, adding a spacious exhibition gallery on top of the Hall of Realms and a monumental portico of slender bronze pillars in the south facade, which opens on to a pedestrian and tree-planted urban environment, intended to link the Retiro Park to the Paseo del Prado. The transition from natural history museum to art campus is thus complete, and new life is breathed into the historical space that first gave rise to the current museum, whose origins lie in the collector monarchs who bequeathed us the formidable works of Titian, Bosch, Velázquez, Rubens, or Goya that are harbored in the Prado.