Modernity understood rupture as an indisputable value, but a century of traumatic experiences has made us cherish continuity. Instead of the tabula rasa of enlightened utopias, which believed to be building a new city for a new man and in the end produced totalitarian nightmares in the urban or social realms, the defense of the stubborn laziness of forms and customs possesses, beyond its ecological and thermodynamic logic, the comforting appeal of gradual change. Few things are as tedious today as the constant provocations in art or architecture that claim as their own the withered avant-gardism of ‘épater les bourgeois’, when in fact nothing is able to shock anymore. And though some architects still attempt the ‘succès de scandale’ offered by violent rupture, public controversy and media visibility, the best of them know well how to combine continuity and innovation.

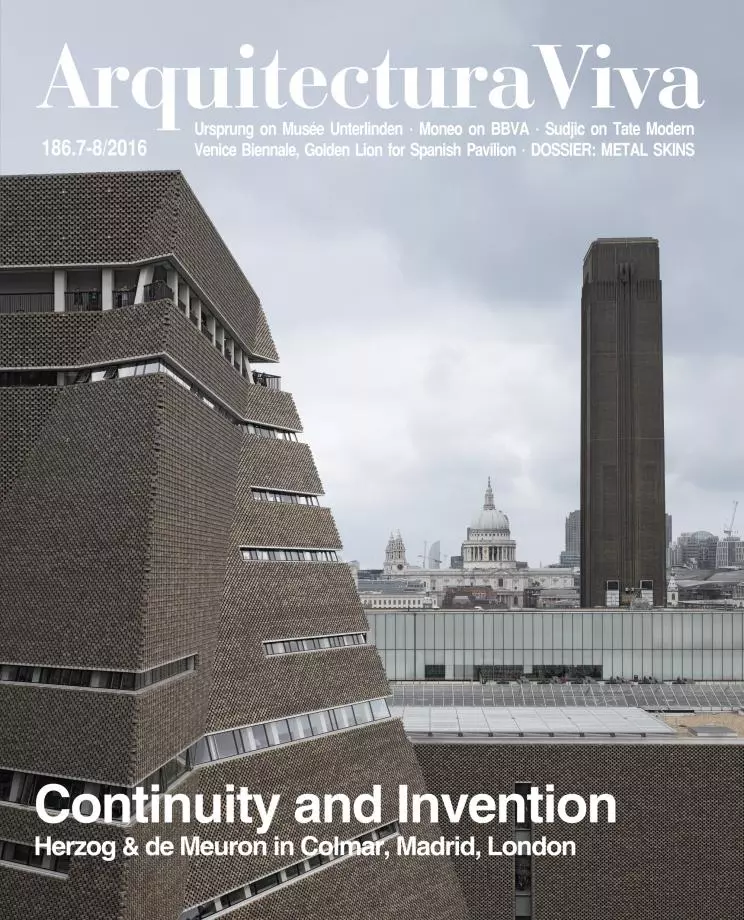

Such is the case of the three works that Herzog & de Meuron have recently completed in Colmar, Madrid and London: three projects that start out from existing structures, remodelled by the architects to give them a renewed identity, and where what was found in the place, far from being understood as a restriction to imaginative freedom, is used as a stimulus that fertilizes and impregnates the new. So it happens in Colmar, where they extend the Musée Unterlinden with a deferentially subterranean volume that emerges in front of the medieval convent with a pavilion that recovers the historic square; in Madrid, where the BBVA headquarters incorporates buildings that were already there to create a dense fabric between narrow, light-filled courtyards; and in London, where the Tate Modern extension uses the tanks of the old power station to create rough, seductive spaces.

But while there is an essential continuity in the three works by the Swiss firm in France, Spain and Great Britain, evident in their respect for the already existing and the urban context, the three also serve as laboratories of material and aesthetic experiences: the huge mute facades of broken brick in Colmar, contemporary and archaic at the same time, in tune with the sculptural concrete staircase, copper roofs or limestone pavement; the light and monumental louvers in Madrid, which wrap the building and colonize as logos the oval-shaped slab that rises over this banking kasbah; and the translucid, ceramic lattice of London, which clads the folded twisting tower whose memorable profile traces the new image of the museum in the urban skyline. Three formidable works that are exemplary in their intelligent interpretation of continuity, and also in their dazzling exercise of invention.